Review by Karl Verhoven

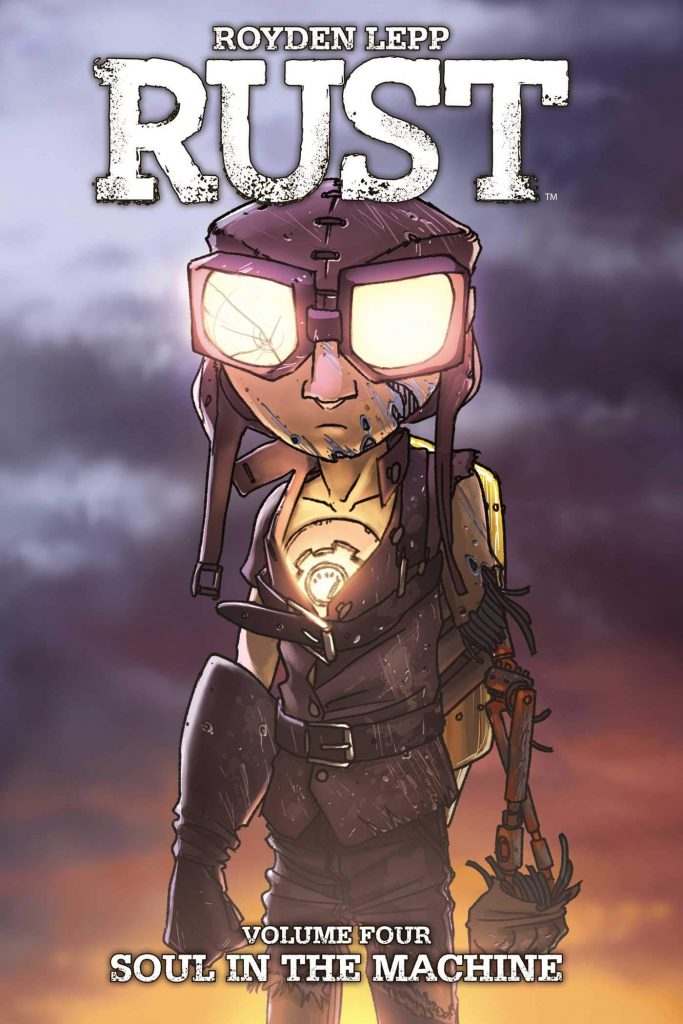

It might be thought that having reached the concluding volume, Royden Lepp has nothing new to offer other than the elements of his story playing out. That seriously underestimates him. The strength of the background and relationships constructed over the first two volumes supplies the heartbreak and tension for Soul in the Machine.

That background is one of a war once fought by robots, in the past, but still in living memory for the older generation. Some electronic tinkering has enabled war robots to be put to use on the Taylor farmstead, but the arrival of Jet, the rocket boy, has changed everything, and the ending to Death of the Rocket Boy was the first series cliffhanger. A sacrifice has been made temporarily stopping the robots surrounding the Taylor farm, and Lepp draws the subtle connection between events of the past and the situation around the Taylor farm when the rocket boy’s creator returns. “We’d forgotten what we were fighting for”, he explains, “we’d forgotten how to hope. So I created a reminder”. It draws Rust closer to Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy, a presumed inspiration Lepp hasn’t drawn any obvious attention to.

The reminder referred to is constant tugging on the heartstrings, as despite knowing the truth, we can’t help but see Jet as human due to his form. In so many ways he is, instilled with an inviolable sense of right and wrong, even when wronged himself. As in previous volumes, the story is rapid because Lepp avoids dialogue wherever possible, and has the storytelling skills to make that count. His sepia toned art supplies an extraordinary mood, and he has a great sense for what makes a memorable image. Perhaps the most memorable is a full page showing a giant robot seen at a distance of several hundred yards. That distance enables Lepp to demonstrate it’s taller than a barn, and ensuring conditions are misty means it’s not exactly defined other than in outline, with the final nice touch being its bright internal lamp. Jet fighting it is equally effective art, the distance maintained and Jet viewed as a streak of light. This is all the more terrifying for being a conflict fought in magnificently envisaged rural isolation. Jet is the only hope. There is nothing else.

When it comes, the actual ending is a real surprise. It’s an instant stop followed by a restart, and Lepp applies the same sentimentality butting up against reality that’s been the foundation of Rust from the beginning. It occurs that the very title indicates a form of decay, and it’s applied well to the threat being dealt with.

For all the action, Rust has been a series showing human feelings, very focussed and subtle. It’s been a great success, warm, creatively ambitious, and marking Lepp as a creator with a bright future.