Review by Karl Verhoven

A whole host of interesting characters were introduced in Gone to Texas, many of whom didn’t survive the experience. The primary ones to concern us, though, are failed hitwoman Tulip O’Hare, rebuilding a relationship with Jesse Custer, somehow now a reverend, and Cassidy, an Irish guy who likes to sleep during the day.

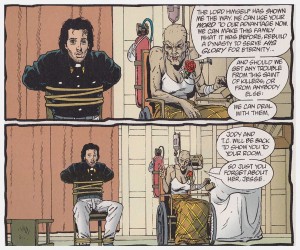

You can’t choose your family, the saying goes, which is just as well as it’s hard to imagine who’d choose the Angels, Custer’s maternal side. Garth Ennis tips the hat to magnificent hillbillys the Angel Gang from Judge Dredd, and the name also serves as ironic commentary. There’s the truly terrifying thug Jody, T.C., who’ll dip his wick anywhere, and Grandma Angel whose fervent belief in the Lord doesn’t preclude brutality, torture and murder in the name of her own redemption.

They’re introduced as a method of explaining Custer’s past. His appalling childhood and the story of his first meeting Tulip then seemingly deserting her are rolled out as the family welcome him back. That they’re immune to Jesse’s power of command, is a glaring plot expedience, and there’s a timely intervention that’s just about consistent in context.

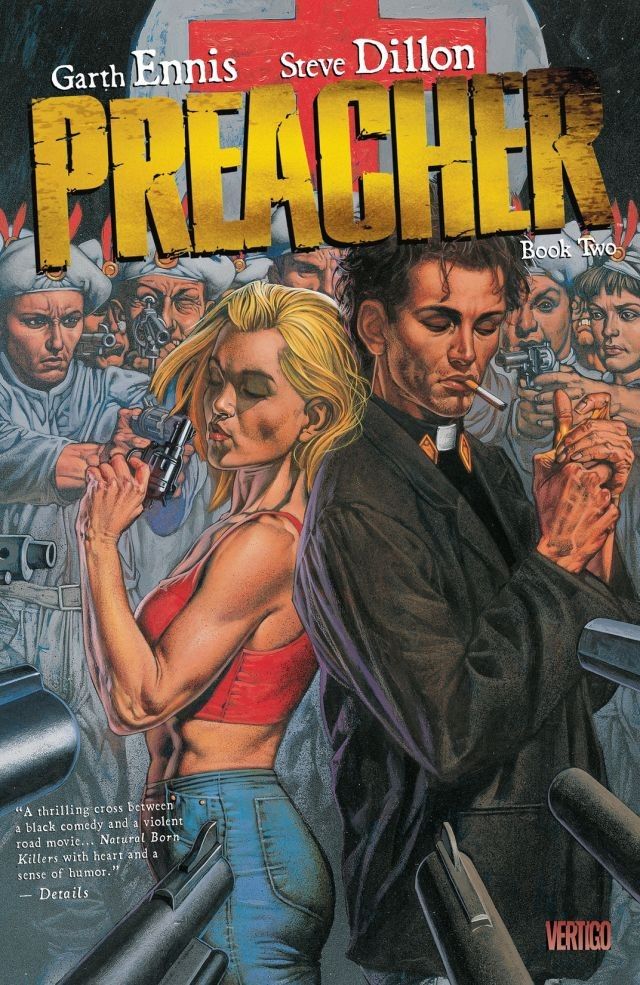

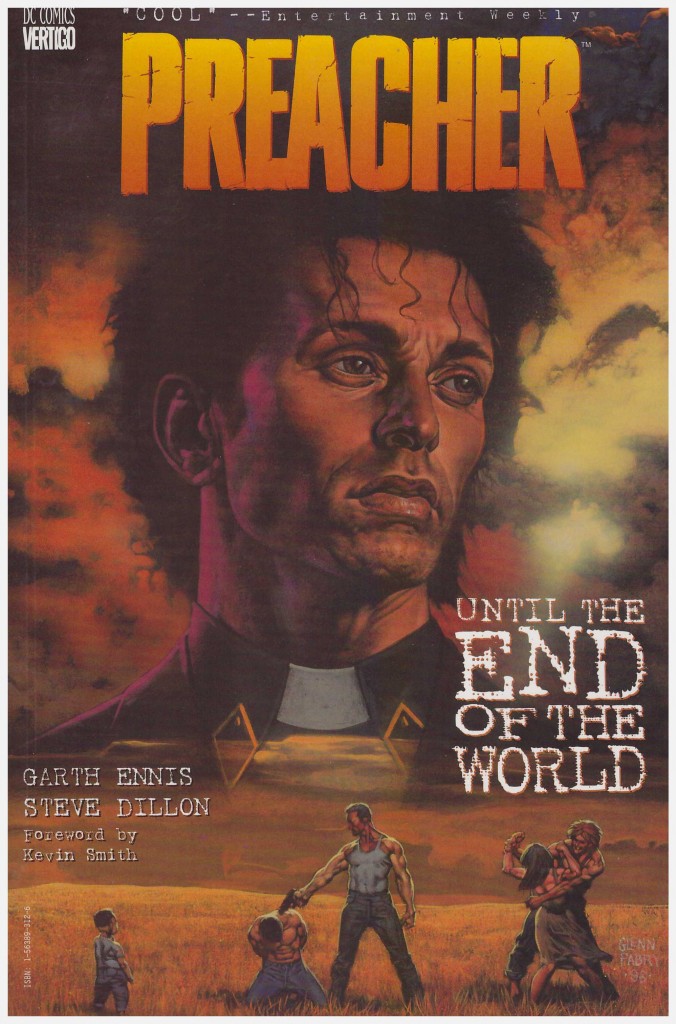

Once again Ennis has created some epicly vile characters and more follow in the second arc reprinted here as the roller-coaster of excess arrives in the form of the Grail and their associates. It’s an organisation created to protect the bloodline of Christ, but there’s a schism. The rebel faction is answers to Starr, memorably designed by Steve Dillon as bearing large scars crossing his right eye to signify his name. That eye now lacks a pupil. Starr has lost the faith and seeks alternative answers, much like Custer, in fact. “The masses will be lucky to get blood into urine”, he notes as he details plans for Custer as a replacement millennium sacrifice. Then there’s Jesus DeSade, possibly not the name on his birth certificate, who relishes indulging in every perversion he can conceive. He possesses a prodigious imagination.

Both villains are well characterised, with Ennis piling on the indignities commensurate with their ruthlessness, arrogance and intent. It’s all the more hilarious for Dillon’s ability to play the material straight, never resorting to cartoon excess.

Much of Preacher’s appeal lies in the dialogue. Ennis’ cast deliver speeches and jokes in the naturalistic manner of good company down the pub. Sadly, liberal peppering of swear words rules out much quoting, and we’re pretty sure neither Ennis nor Custer would have much truck with *#\@√ing substitutions.

These are both better stories than those in Gone to Texas, with celestial elements minimised and bonding maximised. The quality continues with Proud Americans. In 2009 the Preacher books were re-formatted, spreading what was previously nine collections over six hardcover volumes. The homecoming story here is part of Preacher Book One, while the Grail material can be found in Preacher Book Two.