Review by Ian Keogh

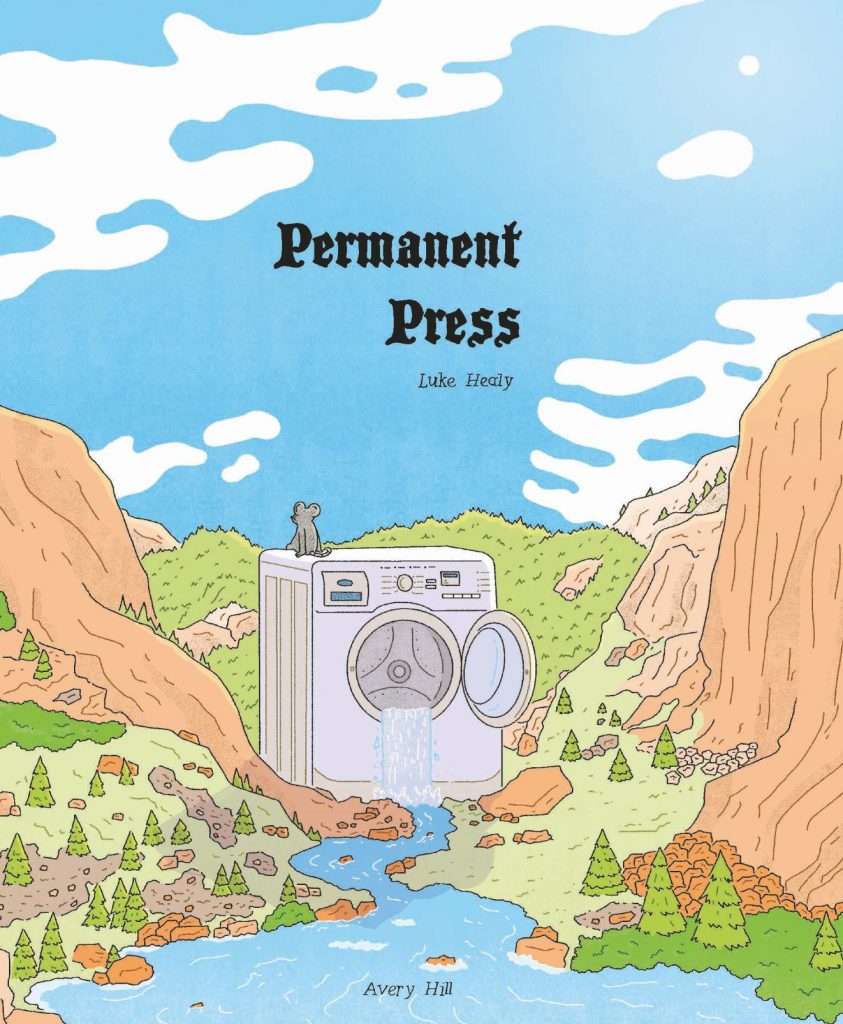

Permanent Press doesn’t begin well, which is a shame, as most of it is sparkling. Luke Healy’s introductory autobiographical ramblings offer a main helping of self-pity, accompanied by side dishes of entitlement and vanity. Few things evoke as little affinity as the redundant cliché of a creator whining about their lack of appreciation. This off-putting prologue is eventually relevant to the layers Healy’s creating, but it’s entirely reasonable to ask if the book would be better without this linking device. Even when descending into surreality late on, it never transcends whining, when the remaining content works very well as two novellas. Its redundant nature is only transcended once, when it links cleverly, offering extra insight to the creation of the remaining content.

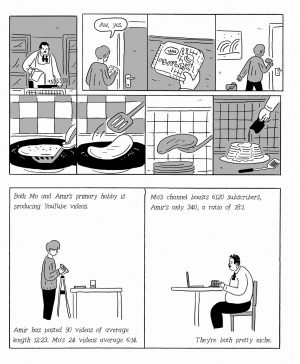

Healy presents that remaining content as if self-produced comics, blocking four sets of panels (or text) over a page for the first, and running them together over two tiers for the second. Both reflect a clever artistic approach, questioning and probing what can be done with comics, largely successful experiments with form, whereas the stories both question compromises necessary in wider creative life.

‘The Unofficial Cuckoo’s Nest Study Companion’ is wonderful, concerning an obscure novel, Cuckoo’s Nest, to be adapted by playwright Robin Huang under the aegis of the BBC and staged in a major London theatre. Her neglected teenage daughter is proving troublesome, the shy writer looks like her ex-husband, and the book is a near monologue that won’t adapt well to the stage as written. Robin becomes as absorbed as Healy in the psuedo-autobiographical sequences, sometimes not seeing the wood for the trees. Surely Healy has worked with the BBC, or has access to someone who has, as he captures the negative aspects of the organisation perfectly from the impossible shifting and contradictory demands placing artistic quality last, to hollow jargon and the constant passing down of responsibility. Everything leads to a wonderfully devastating critique of Cuckoo’s Nest in a classroom and the discovery of some strange stage techniques. It’s funny, provocative and intelligent.

In the context of another autobiographical intrusion, ‘The Big and Small’ is Healy’s irritated response to his father’s comment that numbers are quantitative. Amir and Mo have flats in the same block and are analysed and compared via numerous quantitative figures that of course completely fail to create anything other than the barest impression of personality. Simultaneously it dissects them and probes their difficulties, suggesting that perhaps his father’s comment is of some value. This is when the framing sequences enlighten, the meta element providing additional access to the creation. Was it actually true? It certainly feeds into the theme of fathers that links much of the content.

Healy’s illustrations are elegant, yet distanced other than those sequences in which he and his distracting shadow feature. They’re deceptively simple looking, but convey a pleasing diagrammatic precision, and the switching between styles is effective, Healy at one point questioning the demarcation lines between prose and illustrated fiction.

There’s significantly more about Permanent Press that’s good than poor, and from a creative viewpoint the connecting strands would seem essential, but the unfortunate opening severely diminishes sympathy and expectation. Otherwise it’s vibrantly experimental and enjoyable.