Review by Graham Johnstone

Fantagraphics are to be lauded for discovering and championing unique talents, in this case, Belgium born Oliviér Schrauwen. They brought him to the attention of the anglophone world in their Mome anthology and they’ve carried on publishing him through to 2020’s Portrait of a Drunk.

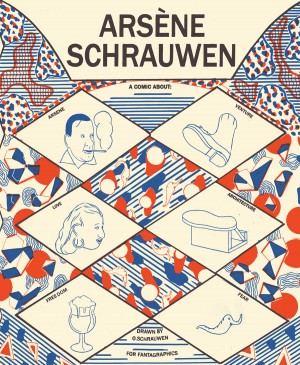

His 2011 debut The Man Who Grew His Beard collected a quirky mix of fantasy, imaginative journeys, and self-reflexive creative experiments, connected only by inclusion of a bearded man. However, that volume’s ‘Congo Chromo’ explored Belgium’s colonial history, acting as a prelude to his dazzling full-length debut Arsène Schrauwen.

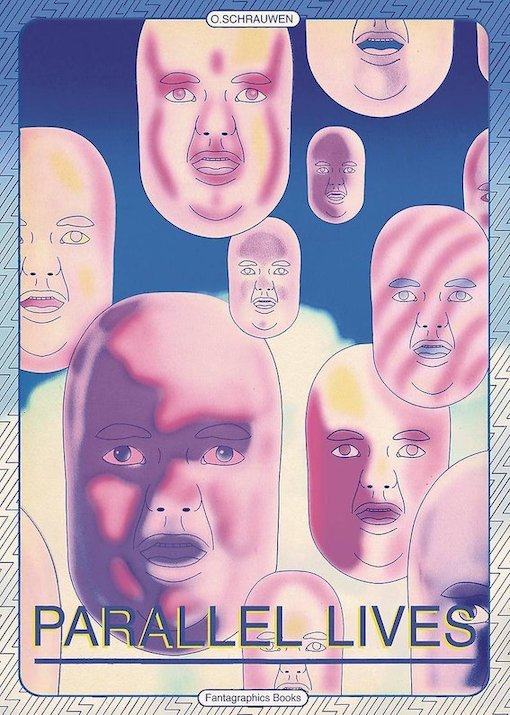

In this second collection, Parallel Lives, subtitled ‘6 Fantastic Stories’, Schrauwen turns his imaginative powers from the regressive politics of the past, to progressive social and sexual futures. In lieu of the bearded man, the connecting device in this volume is Schrauwen avatars, often reflecting our world and time. For example, in ‘Greys’, aliens arrive at a Mr Schrauwen’s home, gather some intimate secretions, and take him aboard their craft. There they bombard him with images of earth’s brutal past and future, juxtaposed with their own harmonious present.

The Parallel Lives are not just between stories in apparently unconnected SF settings, but in the relationships within those stories. In ‘Hello’, Schrauwen broadcasts into the future via an archaic Cathode Ray television. There’s no two-way communication: it reaches an intrigued couple who can’t communicate back, yet they conduct their most intimate activities at their respective sides of the broadcast. Such technological elements serve what’s primarily social science fiction. For example, in ‘Cartoonify’, ‘Oly’ downloads an app to his cerebral cortex, that lets him experience life as a cartoon character, with a cost to his main relationship. The technology is even more intrusive in the social world of ‘The Scatman’, who has a parallel intelligence intrusively narrating his thoughts. These stories are fascinating, and charming, their improvised quality only adding to their appeal.

Consistency of theme is offset by formal and visual variations, exemplified by the final two stories. ‘Mister Yellow’ is compressed into two ink colours, and two pages of inch-square panels; while ‘Space Bodies’ (featured image), is more narratively and visually expansive – suiting its extended exploration of an alien world .

The art reflects the stories’ origins in risograph zines, exploiting a palette of ink options, as opposed to the digital separation of coloured originals for the typical four-colour (CMYK) of commercial printing. Creating with colour in mind, Schrauwen avoids hatched and feathered ink render – mostly limiting himself to line, solid ink and the tone/colour permutations. His judicious use of paint or texture effects for water or skies, is consistent with his charming ‘lo-fi’ aesthetic. In ‘Space Bodies’ he returns to the traditional four colours, but appears to again have created them as separate layers, with ‘wash’ effects evoking the similarly created dreamscapes of Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland. Schrauwen’s art won’t appeal to everyone, but there are some dazzling, luxurious images, with the more casual ones all part of a conscious aesthetic: the artist as ‘naked’ as his characters, frolicking amongst them.

This playfulness extends to the writing. These are meta-fictions – explorations of science fiction sub-genres, and literary devices such as narration, which Oly has in his head, and other characters perform for us. McCay aside, Schrauwen’s nearest reference point is fellow Mome alumnus Dash Shaw with his similarly dismantled colour palettes, playful formality, and humanistic science fiction. As with Little Nemo who always wakes from the dream, these stories lack any real threat, (in itself part of Schrauwen’s playing with narrative expectations), but like Slumberland, Schrauwen’s worlds enchant.