Review by Karl Verhoven

The only consistent member of the Pandora’s Box cast is an old lady seen begging on the streets, who at some point in the story lets the primary character know their future often in confusing terms. Whether they then believe it is of course up to them.

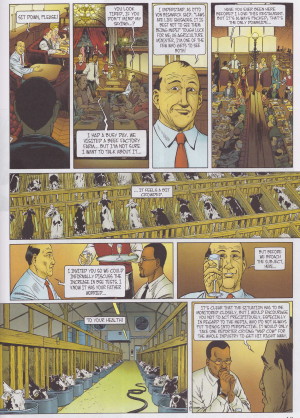

In Gluttony the recipient is Teze. Born in Ethiopia, he was adopted as an infant by a couple of French doctors, and his adopted father Pierre-Paul Egée rose to become Health Minister twenty years later, which is when the main story begins. With a BSE crisis seemingly imminent, Egée appoints his son as Chief of Staff. This political appointment can be justified by Teze’s qualifications. With his own child on the way, Teze is thrown into a world where political concerns often trump the best interests of humanity. “Don’t forget the economic importance of the beef market”, Teze is advised early into his tenure.

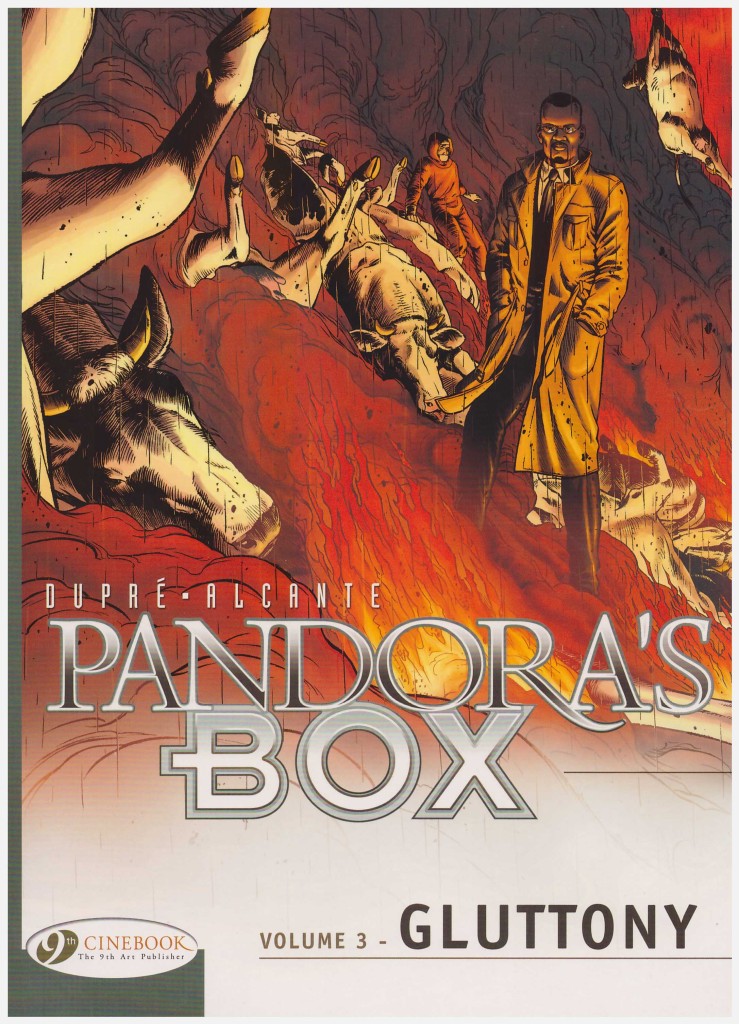

After the comparative disappointment of Sloth, Alcante is back on form, basing much of his story on Britain’s Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy crisis of the 1990s, and the reaction to it in the EU, just transferring the circumstances to France. Brain disease in cows was passed along the food chain to humans, and Alcante inserts some scenes almost directly from real incidents, such as Agriculture Minister John Selwyn-Gummer feeding his daughter a burger as a promotional opportunity at the height of the crisis.

Alcante is scathing about the factory farming on which European food production is based, and unsparing about conveying the horrors of it, among vast amounts of other pertinent information. This is obviously heartfelt on the author’s part, but that has both pros and cons. At times there’s the feeling of being lectured, and it occasionally slows the plot to a crawl, yet there’s a fine sequence set in a restaurant switching between the process involved in getting the food to the table. While almost exactly following the pattern of Britain’s BSE outbreak, the plot also has twists involving corruption and eventually a heart-rending ethical decision needs to be made.

The artists of the series shift along with the narrative spotlight, and Steven Dupré is very good, although his figures seem posed in places. He lays out the story well, effortlessly incorporating the huge amount of dialogue required, and although he disciplines himself to the needs of Alcante’s script here, a quick online check displays an admirable adaptability.

Pandora’s Box next turns its attention to Greed.