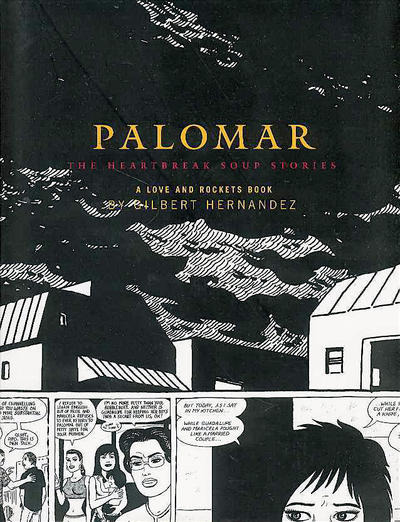

Review by Frank Plowright

It’s applicable across the creative arts that when something is an immense critical or financial success it spawns plenty of imitators. Yet despite Gilbert Hernandez’s dramas set in a fictional small Central American town winning awards and being praised to the skies, there’s not a single subsequent series bearing anything other than a passing similarity. Why is that? The suspicion is that no-one else is willing to put the work into devising such complex histories connecting so many wonderfully constructed, three dimensional personalities.

In choosing a small town Hernandez is aware that isolation breeds both eccentricity and local acceptance of that, and that people have to rub along. The alternative is to leave town, and over the course of Palomar some do, although not always willingly. He begins by detailing the arrival of his signature character, the glamorous Luba, force of nature with four children, none of whom know their fathers. ‘Sopa de Gran Pena’ (‘Heartbreak Soup’) is still very engaging, but also crude and Hernandez finding his way when compared with the later work. It does, however, establish so much of what blossoms. Hernandez is very good at involving children, there are moments of complete whimsy, death is a part of life, and for someone in his mid-twenties when he produced the story there’s a mature understanding of human emotion. It’s a microcosm of humanity, good and bad.

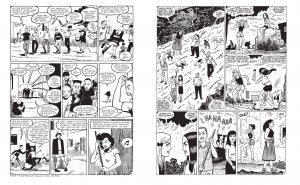

Palomar collects work produced from 1985 to 1996, the sample spread providing art from the first and last years, although Hernandez added to and modified his stories for book publication. While impressing from the start he makes almost continual improvements, with the art something to marvel at throughout. It’s expressive, character rich, thoughtful and elegant, the inking line gradually thinning and the use of black and white contrast becoming more sophisticated. Hernandez is also a restless storyteller, continually experimenting with methods. Years can pass between panels, whimsical inclusions are given later significance and there’s a dense four pages in which the visuals provide a completely different narrative from the text.

From the opening story Hernandez leaps forward ten years, and roughly another ten years have passed by the end. Characters grow and change, continually shaped by events, and Hernandez is no sentimentalist protecting his cast. Not even Luba gets a free pass from tragedy. The actual stories are as rich as the personalities and the art, cleverly plotted, sometimes hinging on what’s been concealed in the past, and always true to the people involved. Someone presumed to be a minor inclusion will carry a later piece, and only toward the end, does it occasionally seem the answers to mysteries have been contrived.

Palomar is phenomenal work from one the greatest ever creators of American comics, and anyone who’s never read these stories has an unknown gap in their lives.

In 2007 Fantagraphics repaginated Hernandez’s work in new bulky paperback editions, and these stories are also found in Heartbreak Soup and Human Diastrophism, the latter including a few stories missing here, where the selection is restricted to material largely occurring in Palomar. It leaves ‘Luba Conquers the World’ toward the end a little bereft of context as several absent connecting stories take place in the USA. Earlier collections of the same material are also available.