Review by Frank Plowright

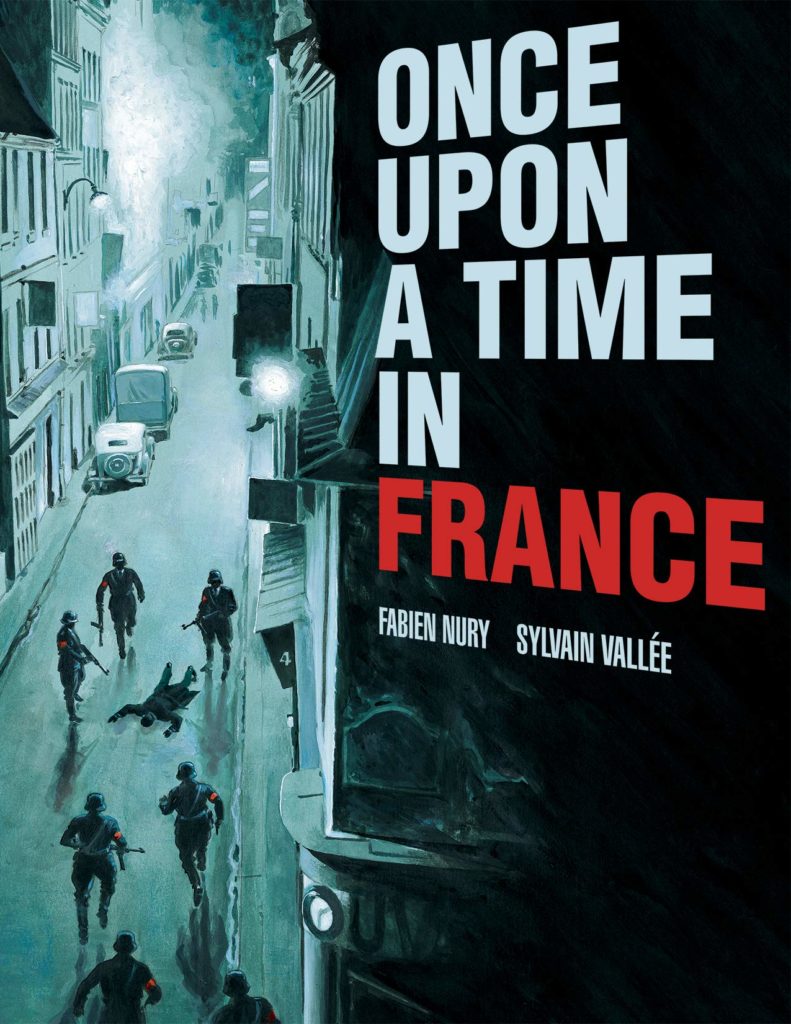

Fabien Nury’s title alone is a statement, linking his extrapolation of a wartime collaborator’s life with the cinematic triumphs of Sergio Leone, but arrogance doesn’t apply as this is a resounding triumph. It’s intelligent, humane and based on the activities of Joseph Joanovici, a Romanian Jew who arrived in France during the 1920s and rose to prominence during the German occupation of World War II. This edition translates all six albums as originally published in France.

Joanovici’s contentious reputation is established over a number of scenes flitting through his life. Is he really a hero of the French liberation as indicated by the certificate he was presented with, a man who saved Jewish lives, or a gangster and war profiteer with friends in high places, many being blackmailed? Those who believe him cornered in 1947 are aware it’s both, among them provincial Judge Jacques Legentil, determined to bring Joanovici to justice.

Nury starts by showing many sides of Joanovici, but emphasises his elusiveness. He trusts very few people, and claims family is his only country, after which he’s shown betraying his wife, the implication being the difference between claim and reality can be applied to his other activities. His conscience certainly isn’t troubled by selling metal to Germany before World War II, while simultaneously supplying France’s needs for the defensive Maginot Line, yet when Germany invades he supplies forged passports disguising the Jewish identities of his factory employees. There’s partial self-interest, but it saves lives.

While Joanovici existed, Nury’s story is largely fictional extrapolation around some known events, brought to life by Sylvain Valée, whose meticulous clear line art is rich, detailed and technically superb. Joanovici wasn’t a man of action. All his deals were conversational in shady rooms, and Valée draws countless scenes of importance, each of them diligently depicted, each differing from the rest. Lacking his intuition and craftsmanship Once Upon a Time in France would be far weaker.

After the opening chapter Nury and Valée take a more linear approach to Joanovici’s activities, following him through World War II from 1940, and out the other side. Complex and contradictory, he’s an astounding opportunist, masterful at playing one person off against another, and prescient enough to know when danger approaches. He looks after his own skin first and foremost, but realises this requires greasing the right palms at the right time, and looking the other way on occasion. His hands are dirty, but he also saved many lives. Much is speculation. Joanovici was illiterate until late in life – the placing of a sign in the opening chapter is a nice touch playing on this – so wrote nothing himself, while testimonies of others all have an element of self-interest in creating a villain to protect themselves. Even in the heat of war, though, some crimes can’t be buried, and Legentil’s pursuit for justice begins in 1946, most of the fifth chapter occupied with his pursuit. An appalling incident in the opening chapter reveals how Nury considers his subject, followed by an ambivalent approach after, but with the fictional Legentil’s pursuit Nury reinforces his view.

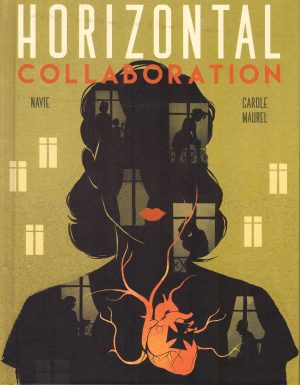

Once Upon a Time in France is a stunning read. It has a satisfying density, investigating ethical issues and grim deeds, not restricted to those with Joanovici’s involvement, yet within the format of a compelling crime thriller with utterly tragic moments. It’s amazingly drawn and won prizes at both of Europe’s most prestigious comic festivals, Angoulême and Lucca, and at a cover price of $29.99 for over 350 pages, it’s astonishingly good value.