Review by Ian Keogh

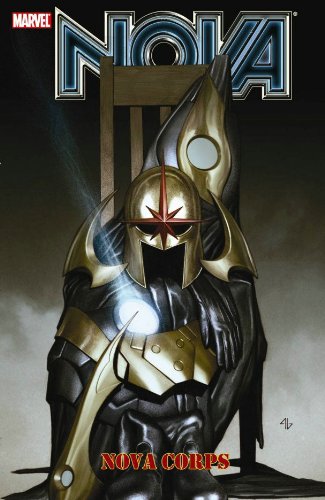

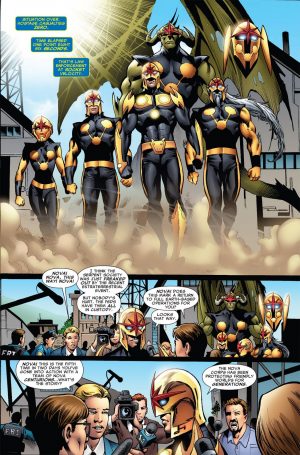

Since the beginning of this series of Nova it’s been presumed that Richard Rider was the only member of the Nova Corps to survive their destruction, yet Secret Invasion ended with the appearance of half a dozen other armoured beings from various alien races.

In Nova Corps Dan Abnett and Andy Lanning investigate aspects of Richard Rider’s past, both as Nova and when he was an ordinary high school student. He’d already reconnected with his family during Secret Invasion, but they’re around for slightly longer than may have been expected, as Nova hasn’t headed straight back into space as he did after his last visit. There’s also a brief look at his time with the New Warriors, and a reunion with some of them. Wherever the series has been based, a key element of Abnett and Lanning’s writing has been unpredictability, and that’s sustained here, with a great final page to every chapter, with the ending to the 21st century material the strongest yet. Let’s just say Richard Rider is in a very different condition when he ends the story.

The Xanadarian Worldmind has managed to reboot itself and find a new home away from Richard Rider, and for the first time Abnett and Lanning investigate what that really means, and what the Worldmind is capable of. A lot, is the short answer. It’s been creating new Nova Corps members on the sly, and has plenty of ambitious plans for reinstituting the Corps throughout the galaxy, plans that Richard isn’t very happy with. The plot cleverly exploits this for suspension, suggesting how easy it might be to suggest something’s for the greater good of the world when individual thinking is curtailed.

Several artists contribute, with regular series penciller Wellinton Alves (sample art) the standout, producing dynamic page after dynamic page. Geraldo Borges on the civilian sequences is again good, although in this collection there are some odd, flat faces, and Andrea Di Vito is great on a surprising final chapter and continues into the following War of Kings.

As Richard’s past is key to the main content, there’s also a new framing sequence around his 1976 origin and early exploits as presented by Marv Wolfman and John Buscema. That’s nicely drawn, but otherwise hasn’t aged well. Wolfman’s attempting to use the template of Spider-Man’s high school days, but the updating of high school student attitudes to 1977 results in some inexplicable behaviour, more to do with artificially upping the drama than any coherent thinking.