Review by Frank Plowright

Was any further Miracleman necessary after the superlative A Dream of Flying? While providing a definitive origin revision, there were questions left unanswered, and a villain left loose. Is there anything original left for Alan Moore to say in a genre sustained by repetition?

Having completely redefined Miracleman, in smaller increments Moore repeats the process for Emil Gargunza, the Lex Luthor of Miracleman’s world, motivated not by greed or power, but fear of the death that comes to everyone. It’s one of several interesting ideas that don’t completely coalesce to build on the promise of the opening. A Dream of Flying began with a headrush of action, then slowed the pace, becoming more reflective and considered, and that’s the prevailing mood in The Red King Syndrome. Long gaps in publication between chapters of the original stories gave Moore plenty of time to consider Miracleman and his world, and this reads as if he’s determined a path, but one requiring necessary stops along the way, not all of which interest him. A deliberately graphic childbirth scene makes what shouldn’t have to be a provocative point, but it’s structured to make that point rather than to service the story, and now reads clumsily. Strangely, the most thrilling aspects are those Moore is railing against, the standard superhero showdown being innovative and imaginative, but afflicted beyond treatment by poor art.

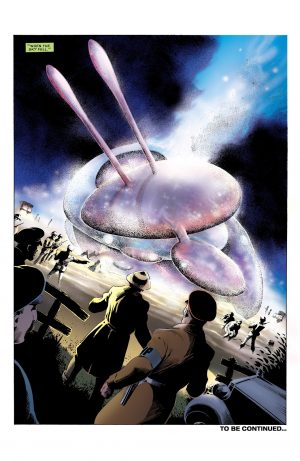

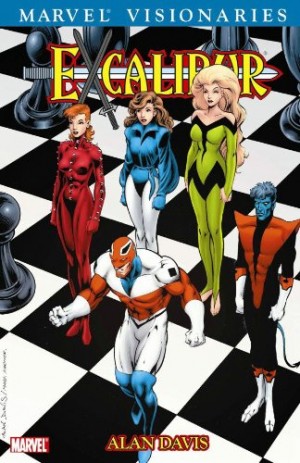

Alan Davis is completely exonerated, producing excellent pages, with his depiction of an alien vessel (sample art) a standout. However, Chuck Austen’s art plummets below the standards set by his predecessors. The bonus material presents his Miracleman pin-ups produced before drawing the series, along with his pencil layouts, all fine, if not quite as imaginative as Davis’ work, but Austen’s inking renders the figures stiff and clumsy, and the expressions manic in places. It’s all the stranger given the far more subtle inking employed on the pin-ups. His stay is brief, but while professional, Rick Veitch’s layouts don’t suit the feature either, closing in too often and failing to convey the necessary grandeur. John Ridgway’s work is fine on an interlude, what in 1985 was a very clever piece of meta-fiction as the cheery 1950s Miracleman and associates struggle to escape what they begin to conceive as fantasy.

Because the standard is so uneven, it’s the ideas that embed themselves more than most of the chapters. A dog given the Miracleman treatment is magnificent, the bureaucrats fearful of discovery are beautifully staged in silhouette by Davis, his visual throwaways in Gargunza’s laboratory startling, and Moore noting the sheer exhaustion of having a baby in the house is novel. Much has been set in place during these stories, and it all pays off in Olympus, but as a standalone graphic novel The Red King Syndrome is the saggy middle section.