Review by Frank Plowright

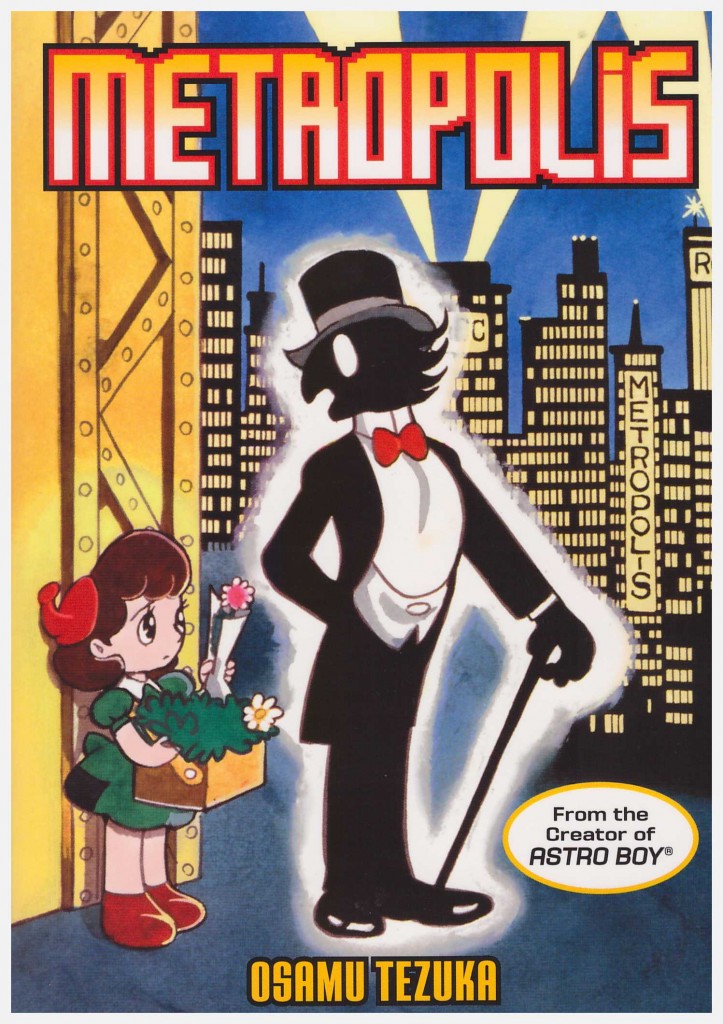

When he began work on Metropolis in 1948 Osamu Tezuka hadn’t seen Frtiz Lang’s film of that title, merely a still depicting the female robot. From that single image Tezuka weaved his own fantasy around the title, churning out imagery of how he viewed the essence of a modern society, which at that time was the USA’s largest cities.

Tezuka’s own medical training and knowledge fed into the story, via what would now be considered a geneticist, Dr Lawson, and his creation of a young child through a mixture of charged genetic soup and unusual solar conditions. Michi is spirited away, and later falls into the care of a detective who has a son of a similar age.

Metropolis is a very episodic story, reflecting its original serial presentation, and the meandering reflects Tezuka working to a strict deadline requiring him to pull in sequences originally planned for other works. Some drag, but others remain compelling, if fuelled by a compelling sense of parental loyalty instilled in Michi, and the ending is surprisingly effective and unsentimental.

There’s a distinct Western slant to the storytelling and one wonders if Tezuka had seen Tintin at the time. There are moments when he seems to be adapting the style, but exaggerating it for maniacally detailed crown scenes. It’s not listed by Tezuka among the works that influenced Metropolis, these including Les Miserables, and uncertainty about whether he’d seen Superman. Tezuka, though is far more than some collage artist, and even at this early and prolific stage of his career he supplies innovative narrative devices of his own creation, including a flashback sequence that reverses the traditional black and white of comics, and Michi being genderless, so those Michi meets impose their own views upon the child.

Tezuka’s repertory cast is already in place, with several appearing here beyond the starring role for Hedeoyaji as Inspector Mustachio and the debut of the villainous Duke Red. There are also numerous homages, to Mickey Mouse, Sherlock Holmes and Arsène Lupin among others. Elements from Metropolis would later funnel into Astro Boy: the genius scientist working in isolation, his naïve child creation and the super strength.

While playful and meandering, Metropolis also examines many themes at the heart of science fiction. There’s the relationship of man and machine, what constitutes life, identity in a technological society, and a basic urge for power and control. At its heart, though, it’s a story for children lacking the layered approach of Tezuka’s later work. An anime adaptation was released in 2001.