Review by Frank Plowright

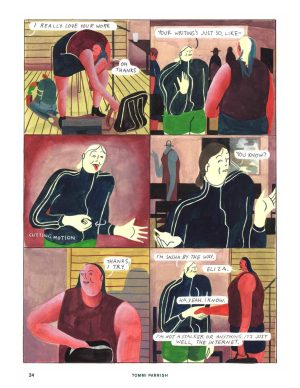

Eliza’s upbringing was far from ideal, but she’s worked hard to dispel demons she still has, afraid of passing them on to her own son Justin. Part of the process is attending AA meetings, and another outlet is poetry throwdowns at a local venue. It’s after a gig that she meets Sasha, touched by the rawness of Eliza’s work.

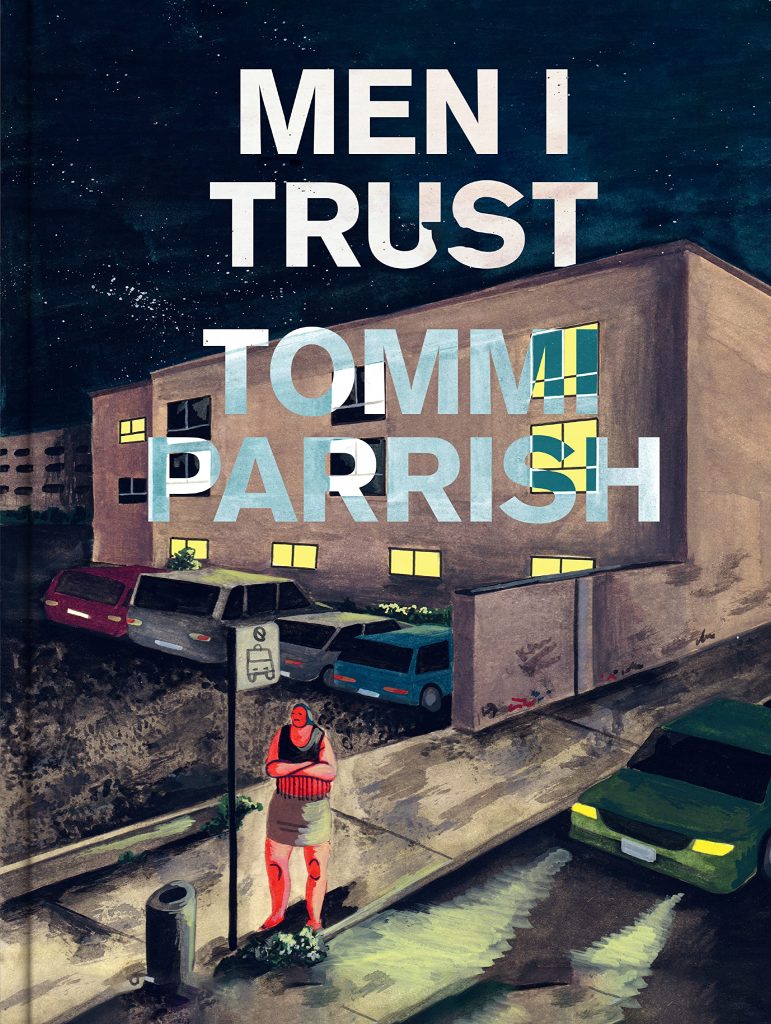

A rawness about Tommi Parrish’s artwork is the immediacy of Men I Trust, likely to be something that appeals instantly or not at all. She paints bright panels without depth, and from a distance people have massively disproportionate tiny heads, giving the impression of everyone hulking out as they’re walking along. It’s entirely random, and there are some panels in which Justin appears larger than Eliza. This may indicate emotional manipulation, times when Justin controls his mother, but there’s no consistency about the size.

The bulk of Men I Trust concerns the friendship that develops between Eliza and the also fractured Sasha, and there’s a contrast between the artistic flights of fancy and a commitment to the observational reality of mundane conversations. These are extended by including pauses and interruptions, and many say so little over several pages, but the aftermath of the conversations are interesting, the effect they have on Eliza and Sandra. Both are reaching out in the only way they know how, but not in a way that immediately connects with the other. The awkwardness is honest and touching, but also reflect Parrish’s likely connection with an audience. There’s something here, but the method of communication is limited.

An attempt is made to introduce wider social issues via the smarmy host of a TV show that renovates old properties, unconcerned about evicting the poor residents to restore the previous glamour, but it’s too transient to be anything other than lip service.

Where Men I Trust is most effective is in raising questions about commitment. Is Sasha’s mother an uncaring, manipulative woman who’s never listening, or is she someone who’s heard the same distressing comments for so long she can no longer answer them effectively? That would depend on your viewpoint. Readers are seemingly expected to sympathise with Sasha, yet earlier there’s been very purposely placed dialogue about people who just suck others dry. As Men I Trust continues, there’s a definite sense of repurposing the title, and the primary question becomes about where to draw a line. When does someone whose intentions are seemingly good and who obviously needs help become too draining?

That Parrish has something to say raises the question as to whether it would be better said via collaboration with a different artist. Is the idea of reaching more people with a more conventional style a betrayal of personal integrity and vision?