Review by Frank Plowright

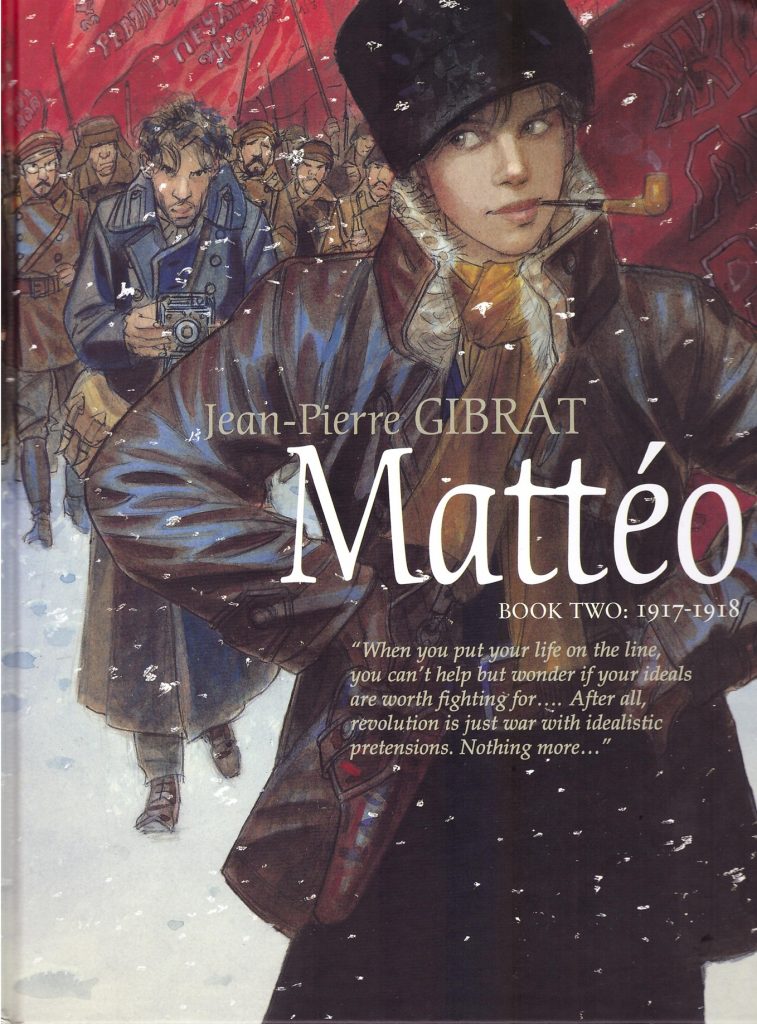

When last seen, Mattéo Cortes’ mother made a life-changing decision for him, taking him by boat to Spain, in order that he avoids the girl he loved, who wasn’t for him, and any trouble that may come from that. As seen in Book One, his chances of survival were higher in the nation of his father’s birth than fighting for the French forces during World War I. Jean-Pierre Gibrat opens Book Two with Mattéo returning home on the anniversary of his father’s death, two years older, espousing anarchist ideology, and about to depart for Russia in order to take part in the revolution.

Despite his experiences of trench warfare, Mattéo retains a youthful romanticism, not always certain why he does something, but with a gut feeling he’s acting for the best. It was the way he approached the trenches, and it’s the way he approaches Russia, supplied with a camera by the Spanish anarchists to record his exploits. Gibrat’s already established Mattéo as someone able to roll with whatever life throws at him, and that’s an essential characteristic in revolutionary Russia, with assorted forces jockeying for dominance and at each other’s throats. Once again, reality is very different from the heroic activities Mattéo anticipated, while his more besotted companion manages a philosophical defence of the ends justifying the means.

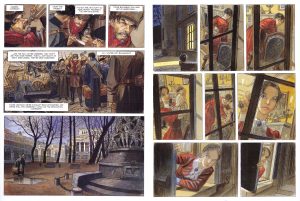

As with any other book by Gibrat, no matter how involving, layered and fascinating the story might be, and this is all of them, the immediate selling point is his phenomenal figurative art. Gibrat takes his lead from the harsh conditions in Russia to determine the overall look, and again produces page after page of gorgeous watercoloured personalities, and researched locations exceptionally rendered, beauty applied to violent history. There’s the possibility that the art quality leads to Gibrat’s writing being undervalued. It’s a fair match, subtle, emotional, dramatic and engrossing. Mattéo has been created to be shaped by experience, to evolve over time, and by placing him within conflict, Gibrat ensures he acquires a breadth and develops as a person. By the end of 1918 he’s disillusioned with almost every aspect of his life, all idealism seemingly knocked out of him as he faces an uncertain fate. Gibrat next picks up on him in 1936.