Review by Ian Keogh

Macbeth’s tragedy of a decent man corrupted by ambition and brought down by unlikely fate is among the most acclaimed and familiar of William Shakespeare’s plays. It can be endlessly analysed for themes and meanings, but even without the additional clever layers it still stands as a cracking story with well worked foreshadowing. Once well into his descent Macbeth believes himself beyond reprisal, yet what seem impossible predicted circumstances contrive to bring him down.

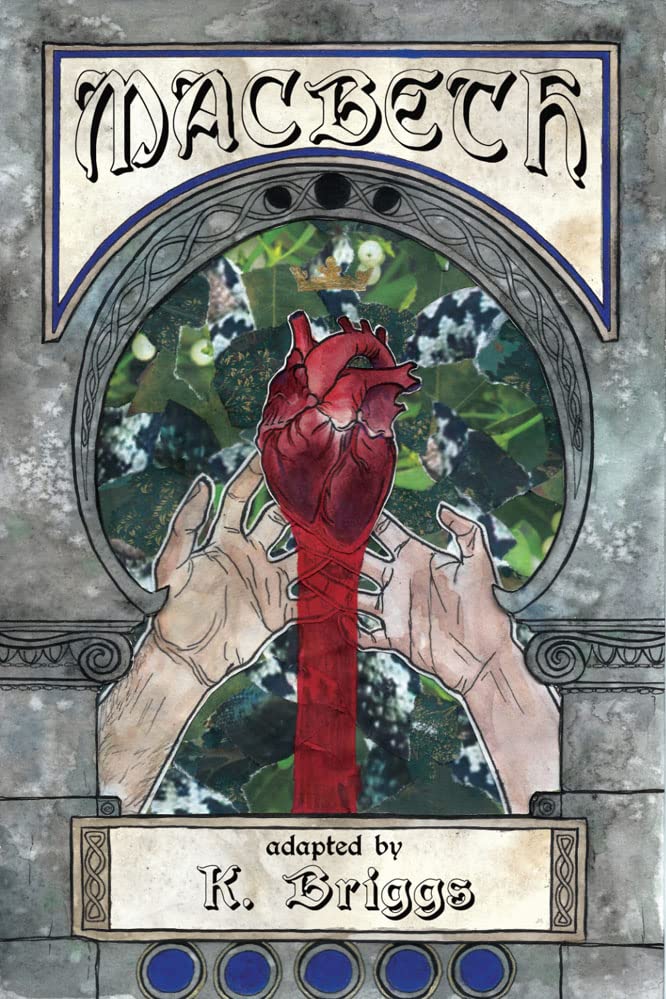

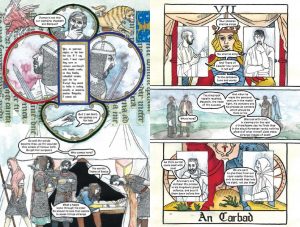

The play has been adapted into comics before, but never as thoughtfully as the fine art methodology applied by K. Briggs. Hers is a restless approach, never sticking to the single application, so colour montages sit alongside more straightforward black and white storytelling, which then gives way to ethereal watercolours, stained glass windows or tarot cards. For symbolism we see inside people or see what’s wrapped around them, and Briggs also feeds in period artistic styles. The short is that whatever Briggs considers suitable for any phase of the adaptation is used without consideration of the usual uniformity applied to a graphic novel. The result could be an unholy mess, but at their best those illustrations re-interpret scenes for new appraisal. Straightforward sequences are rare, and the people in them can be surprisingly contemporary looking, although Briggs is weakest when presenting people naturalistically drawn as the posed quality associated with reference is apparent. A bald Macbeth is a distinctive touch.

Just as no compromises are made with the art, compromises are absent when it comes to Shakespeare’s language. This isn’t a convenient modernisation providing the plot without the sometimes impenetrable phrasing, but a celebration of the text, complete with all its difficulties. For some that will be a drawback and for others a glorious reaffirmation of something that shouldn’t be simplified for greatest possible consumption. What may not be immediately apparent is how well Briggs has adapted the plot and flow of dialogue to individual pages in order to match her visual approach. It’s background technique, but so well handled it deserves highlighting.

Strip away the language and Macbeth is a compelling drama, intended as populist entertainment in its day, using dramatic methods that have been applied to soap operas for decades, and Briggs brings that through. The primary motivator, though, is the audacious art, as Briggs constantly surprises with how a scene is defined in an astonishing testament to her imagination. You’ll want to turn the pages just to see how Briggs frames the next scene.

Could anyone adapting Macbeth to comics better this? It’s doubtful. It’s a magnificent achievement.