Review by Ian Keogh

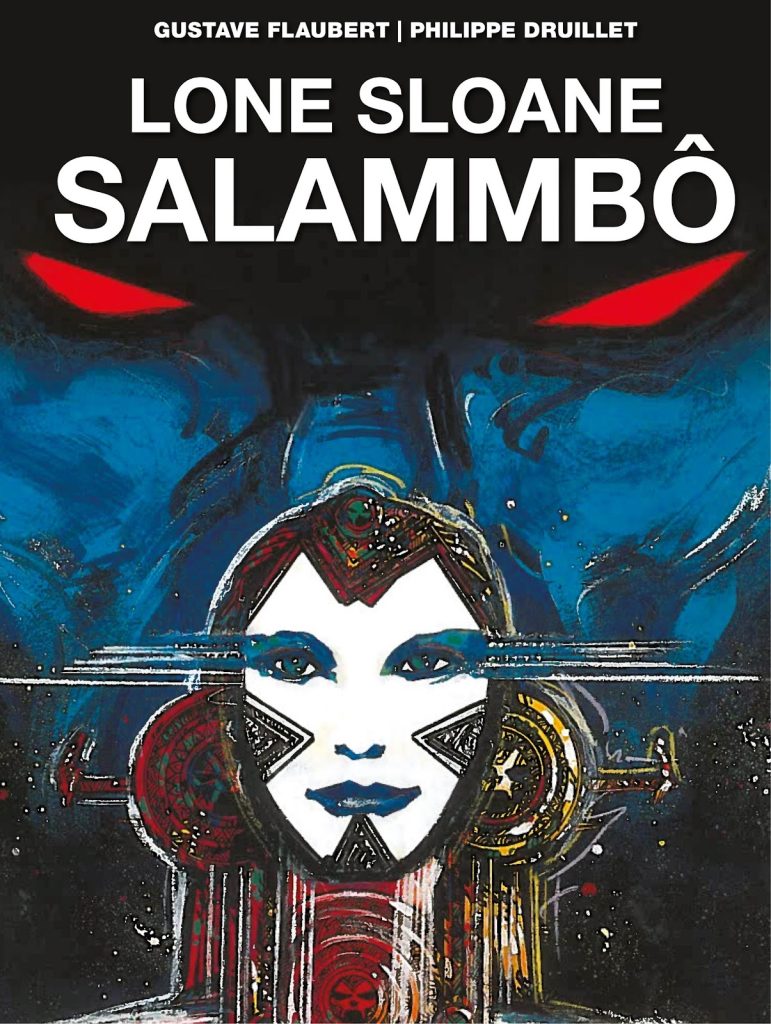

Salammbô is Philippe Druillet’s fourth Lone Sloane outing (discounting the first book under that name as yet not available in English and barely recognisable as the same feature). The English version combines what was originally serialised between 1979 and 1985, and subsequently released as three French volumes before first being combined into a single French edition in 1989.

Let’s start with the credit for French literary great Gustave Flaubert as writer. It’s because Druillet has re-imagined Flaubert’s novel Salammbô, which some will consider heresy. It’s set in the ancient city of Cartharge where a war has just been won via the use of mercenaries they’re unable to pay, so the mercenaries set about putting Carthage under siege. In his introduction Druillet notes his respect for Flaubert’s original novel, and how the text has been scrupulously preserved, meaning far more work than usual for translator Edward Gauvin (unless he just used an out of copyright translation).

A collaboration across a century with the long dead Flaubert supplies a structure to Salammbô lacking in Druillet’s solo Lone Sloane adventures. Sloane is cast as Mâtho, the mercenary who becomes besotted with Salammbô, daughter of Carthage’s ruler, in his world the woman he’s waited centuries to meet.

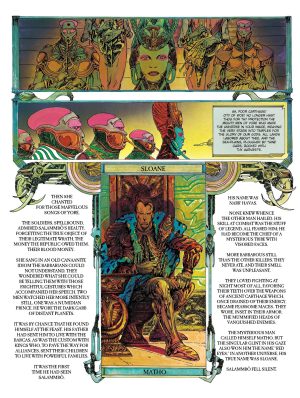

Impossible as it may seem to those who’ve read Gail and Druillet’s earlier graphic novels, his art has become even more detailed, one adjustment being the addition of decorative frames to his spreads. However, for the first time in this series Druillet’s art becomes a hindrance.

Over the opening volume everything proceeds more or less to plan. The adaptation is relatively faithful, the core cast are introduced, the thrust of the story is established and the illustration is stunning, even when surrounded by large blocks of text. There’s power, grace and imagination, and absolutely no skimping on any kind of detail. The second part is more problematical as Druillet depicts Salammbô via photographs merged with his art. He’s used this technique before, but the highlighting of absolute realism with an arch-stylist doesn’t sit well. Additionally, what does it say about Druillet’s view of his own art when he represents perfection photographically? However, the essence of adapting the novel remains.

It’s with the third volume, that the wheels come off. Druillet has been astonishingly disciplined in tying himself to the text, which is the polar opposite of his usual approach to comics. He’s seemingly had enough by the conclusion. Here he discards much plot and several characters in favour of highlighting the battle scenes, although at least Salammbô is no longer a photograph. As illustrations these are phenomenal, insanely detailed and imaginative in depicting the horror of vast armies clashing. As any form of story, though, they fail the test.

As ever with Druillet, the art is so magnificent that the assessment becomes how much value there is to it when the accompanying story falls short. Two thirds of Salammbô is very good indeed, and if Druillet’s pages outweigh any storytelling considerations then so is the final third.

In Flaubert’s Salammbô Mâtho dies, but Druillet fudges the ending to ensure Sloane’s available for Chaos.