Review by Frank Plowright

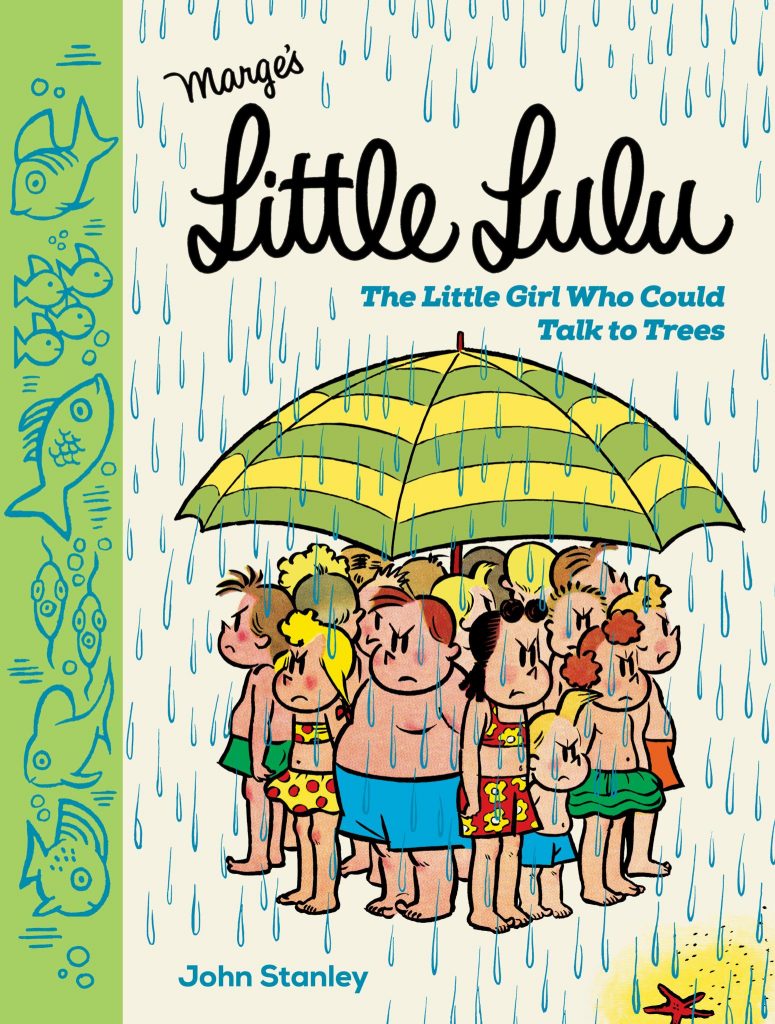

By late 1950 Little Lulu had entered a golden era lasting until John Stanley’s 1959 departure. 27 stories are selected for our delight from a three year period, but such is the overall quality a completely different collection could be compiled and be equally good.

There is perhaps a caveat to that, as ‘Five Little Boys’ is a standout, and the single most-reprinted Little Lulu story. While certainly top drawer, several others here match it for insight, imagination and ingenuity, but perhaps not for the pain of Lulu’s humiliation at the hands of Wilbur Van Snobbe, undergoing an initiation to join the boys’ club. He bets them he can persuade Lulu to follow him on all fours, led by a dog lead, and achieves this. Thankfully Lulu’s revenge is equally embarrassing, and inflicted not just on Wilbur, but the boys who egged him on.

While Stanley’s never overt about his social principles during the course of Little Lulu, they’re nonetheless discernable. He has every sympathy for the poor little girl in the stories Lulu tells Alvin, who acts as a metaphor for the disenfranchised in a world of witches, royalty and the occasional beast, and conversely barely any sympathy for the attitudes of rich kid Wilbur. As pointed out by editor Frank M. Young’s accompanying essay, a story about Lulu sleeping for twenty years and awakening in the future (complete with beard) features commentary on the isolation of the then developing suburban housing estates.

Generally Stanley errs toward avoiding potential complaints from parents and any poor behaviour receives its come-uppance, but he does have a vent in Alvin. Being younger than Lulu and Tubby, he’s supremely selfish and ungrateful, especially via grumpy comments about Lulu’s wonderful stories, yet he often still comes out better off, here one time after having been a complete pain at the beach all day.

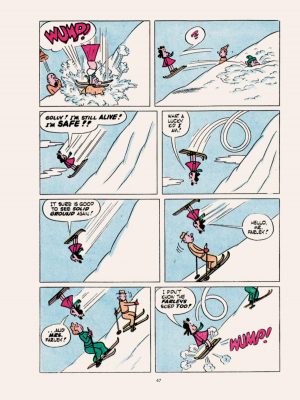

Once again, it’s disappointing to note how little credit is given to Irving Tripp, who drew most of the stories so delightfully, his contribution reduced to a couple of mention in Young’s essay. By these stories he’s begun to be assisted on backgrounds by Gordon Rose, although it would take an expert to notice the difference. His resolute grounding supplies an extra level of comedy to Stanley’s wild imagination, the collaboration working beautifully on the sample art of Lulu’s skiing mishap, which wouldn’t be nearly as funny if exaggerated to be so. In comparison the two stories here Stanley drew himself are competent, but less imaginatively drawn, the viewpoint pulled in too far. Both are uncommonly short, so it’s possible they may have been deadline fillers.

Breaking with the policy of the previous two collections, this outing does feature an introduction: that of Witch Hazel, creeping cackling from the sea to seal Lulu’s stand-in, the poor little girl, within a rock. Young’s essay notes she’ll ultimately end the surreal flights of fantasy in the stories Lulu tells Alvin, but the poor little girl constantly set upon by the malicious witch and eventually outwitting her are also extremely creative tales that became great crowd-pleasers.

Beyond the diminishing of Tripp there’s no cause for complaint about this selection of wonderful stories from one of the greatest runs of American comics. Is it ironic that the collection is published in Canada?