Review by Frank Plowright

Life is Strange is an eerie video game, reuniting former childhood friends Max Caulfield and Chloe Price as they eventually resolve to discover what happened to a missing person Chloe knew. This is helped by Max’s ability to reverse time. The game cultivates a deliberately mysterious atmosphere and emphasises that something altered for the common good in the past may have negative consequences in the future.

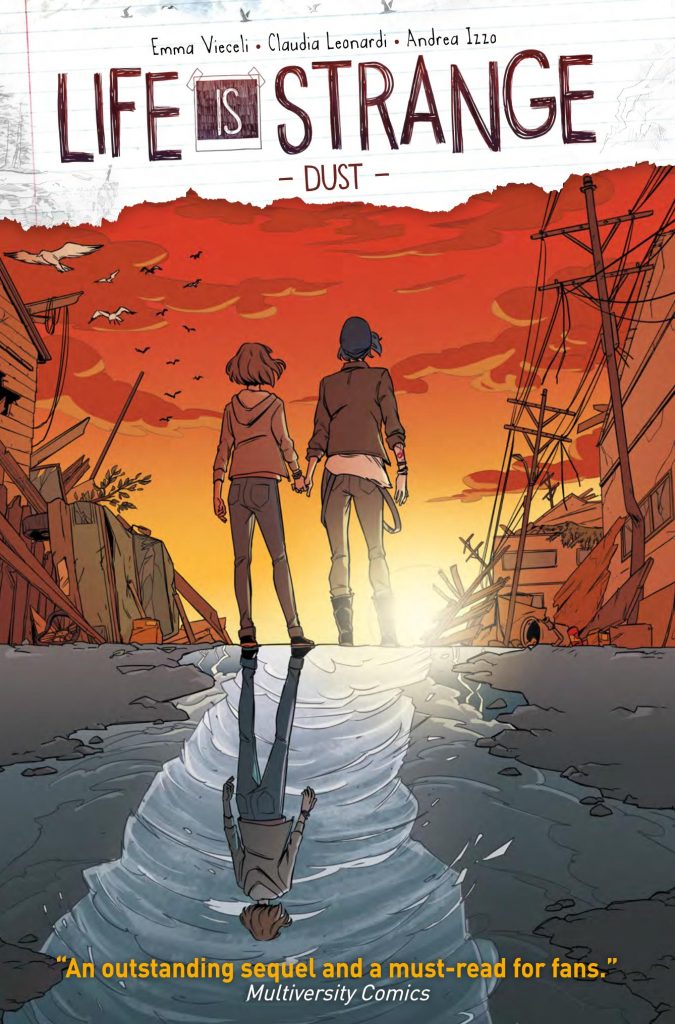

Some of Titan’s graphic novels originating from video games have been limited by the source being an action game, but Life is Strange is deliberately constructed to be a more open and less led experience, which gives creators Emma Vieceli and Claudia Leonardi a broader canvas to work on. In the game Max brings back Chloe from the dead very early, but the inevitable consequence in every scenario played out appears to be a hurricane devastating their home town of Arcadia Bay. That’s what occurred in the reality the creators explore a year later, when Max is having some strange experiences, indicating she’s been travelling back in time, but unknowingly. The answer, somehow, would appear to be in Arcadia Bay, now commemorating the first anniversary of the hurricane.

The nature of constantly travelling back to alternate realities with alternate outcomes layers Dust with complications. Is there a way that Chloe can be saved without Arcadia being devastated by a hurricane? The two have been inextricably linked in the game, but is this inevitable? Vieceli hangs a heavy air of melancholy over Dust, with the constant nagging thought that perhaps something different could have been tried well applied to Max and Chloe. She’s also good at exploring them through the eyes of others, introducing new characters aware there’s been tragedy in their lives without fully understanding.

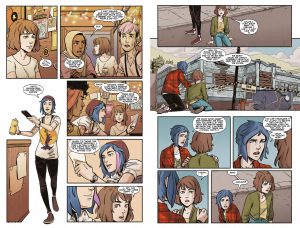

Leonardi’s art is very good at conveying emotional moments through posture and facial expressions, giving Max a constant sadness. She doesn’t attempt to copy the 3-D rendered look of the game, going instead for a more stylised realism, although at times Max and Chloe don’t have a sense of weight about them. In places this is necessary as a disorienting effect of time flashbacks, but it affects other scenes.

Vieceli takes the game’s broad theme of travelling back in time, and applies a background of meeting and talking to people, but what she works most with is her own plot device, or at least one borrowed from the Quantum Leap TV show, which she’s honest enough to credit. It leads on naturally from what’s been established in the game, while the inherent sadness and prevailing anticipation of doom also brings to mind The Time Traveller’s Wife. It all leaves Dust a touching graphic novel able to stand separate from the game that spawned it as a reflective and warm hearted character exploration.