Review by Ian Keogh

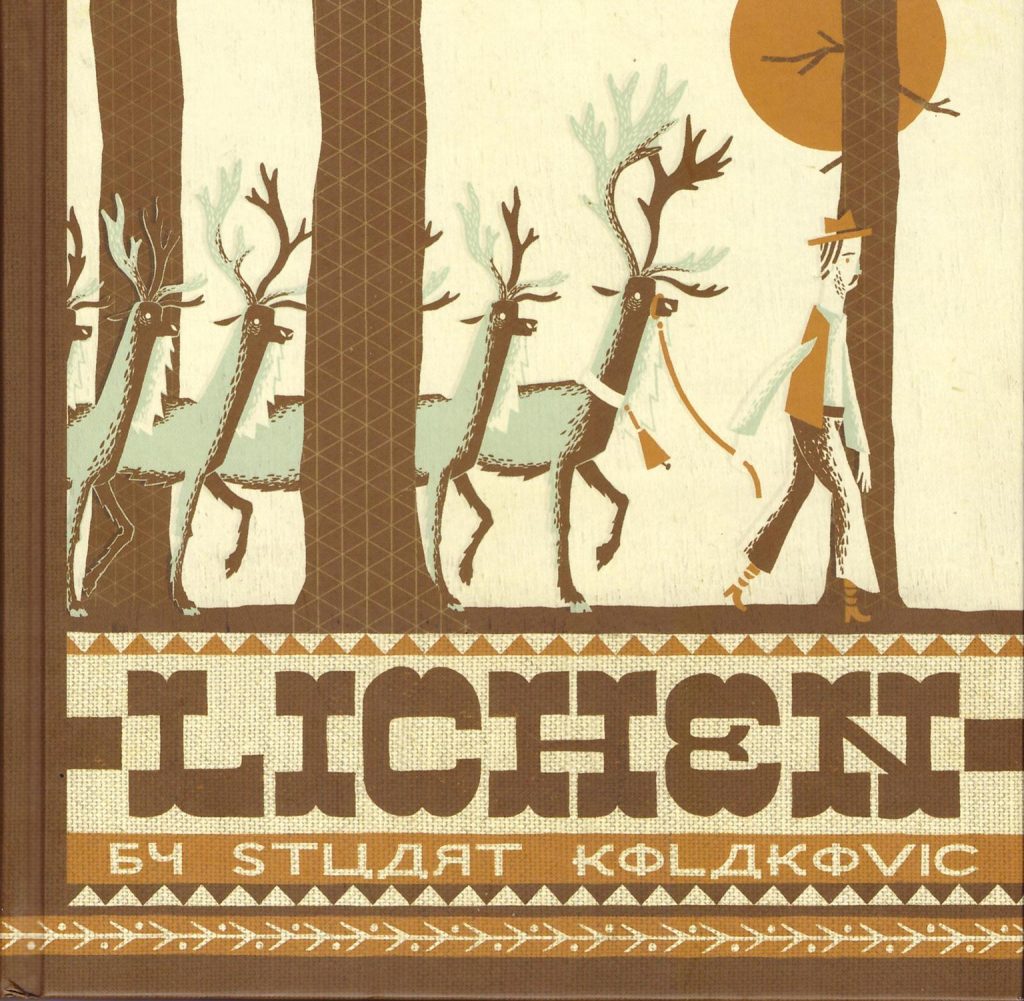

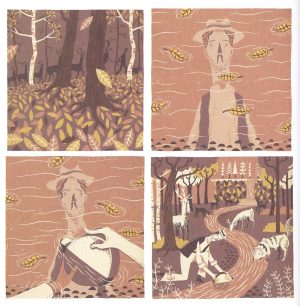

Lichen is a strangely engaging graphic novel constantly moving away from it seems to be. An opening pair of pages presents nine square panels in a square grid, their contents barely connected and sometimes abstract, raising thoughts of Stuart Kolakovic being overly influenced by Chris Ware. This isn’t entirely dispelled by the first third of his story being wordless, the panels settling down into a square grid of four. The art within is intricate, flat and prioritises decorative design, each page presenting a different colour scheme, but always muted. Furthermore, the storytelling is extremely decompressed, every mundane moment legitimised, but given the work put into each panel this isn’t poor storytelling. As Kolakovic continues his calm way, the realisation arrives that he’s showing us the long and arduous journey of his protagonist. This is obviously not in real time, but by following in such detail readers arrive at greater comprehension than would be achieved by a few narrative captions.

We’re learning about a woodsman, a stoic, isolated type who each year takes a herd of deer to the city. He needs to follow an arduous route dictated by the deer needing to feed on lichen patches along the way. The opening pages may seem random illustrations, but explain much about the woodsman, his way of life, the dangers he faces and the changing of the seasons. Kolacovic conceives clever visual devices to transmit information, such as flocks of birds in triangular formation, the birds made out if flying close, while reduced to abstract triangles when viewed from distance. A third of the way through our silent woodsman performs an act of kindness from the heart, and with that comes Lichen’s second major character. He joins the journey, alternately a companion or a nuisance, but a constant tempter. Until that point Lichen has been a pastoral drama, but now possibly moves into fantasy. The key to whether or not the genre changes is if we believe the person to be capable of what he claims.

Two-thirds of the way through, the woodsman and his companion reach the city, and Kolakovic pulls another surprise, shifting further into the spiritual and hallucinogenic, confirming that no lies have been told. This begins the path to a heartbreaking conclusion. To say too much would ruin a carefully devised comment on the futility of some shortcuts in some cases. Faith is key, however, explored in enigmatic fashion from the start, and having an increasing importance as Lichen progresses. Because the woodsman maintains his silence throughout it’s possible to project all kinds of interpretations on what he does and sees at pivotal story junctures, but whatever the interpretation he remains sympathetic. Regret, isolation and the human need for companionship all converge for a strong emotional experience marking Kolakovic as a talent to watch in the future.