Review by Ian Keogh

In his introduction Marwan Kahil notes that while Leonardo da Vinci’s work remains globally famous centuries after his death, most of us know little about the man himself. He’s right. An example might be the realisation that the name by which he’s known translates as ‘Leonardo from Vinci’. His family name is lost to history.

That means there’s so little information available from which Kahil can weave a traditional biography, and the route taken of putting words into mouths as incidents are related is profoundly discomforting. Whether down to the original writing or an unsympathetic translation, the result is people pictured as having unnatural conversations to pass on the information to readers. Scenes are extrapolated from the little information known, yet so often transmit as trite.

Kahil sifts interludes from later life between chronological sequences detailing Leonardo’s progression from child to apprentice to master, impressing all he works with. However, he drifts from person to person and place to place discarding characters along the way, readers never knowing them well enough to care when tragedy occurs a page or two after their introduction. Kahil also references the political intrigues of the era, but without contextualising them. We’re given to understand, for instance, that the assassination of Guiliano de Medici is profoundly significant but he’s been depicted as a passing acquaintance, not anyone with the depth to send Leonardo into depression. This, perhaps, is down to Kahil’s coyness about Leonardo’s attraction to men, hinted at, but never explored. Was Guiliano a lover or object affection despite his having girlfriends? You won’t find out here.

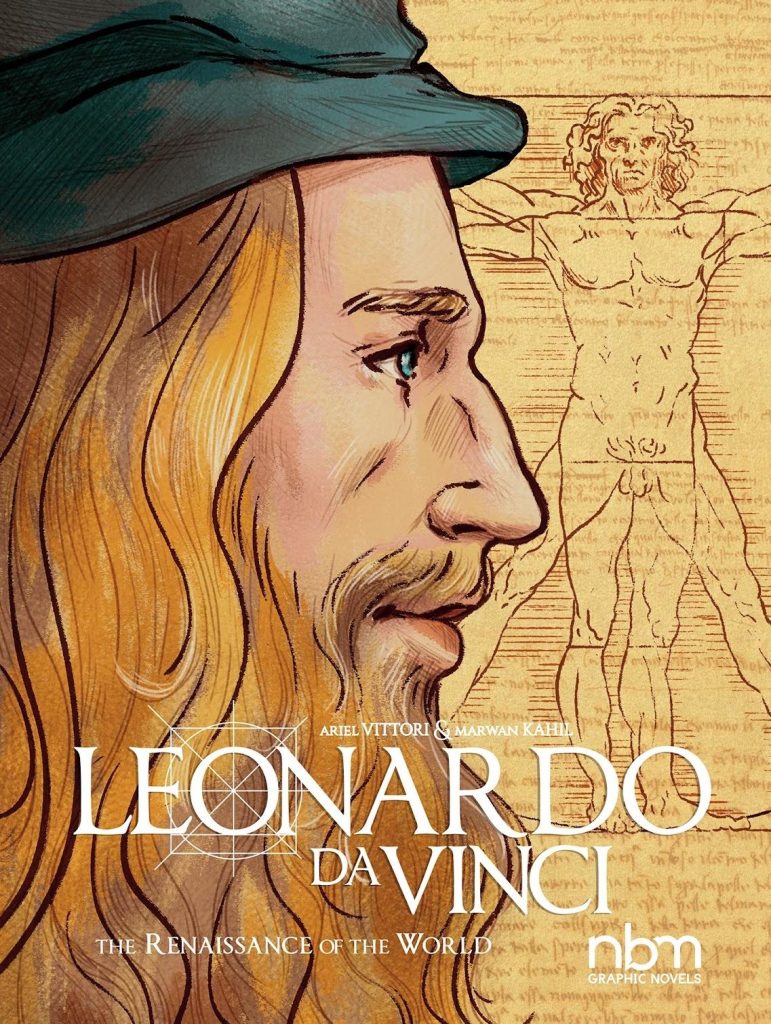

To expect any artist to match Leonardo’s skills is unrealistic, and there’s no requirement to adopt his naturalism in illustrating his life, so Ariel Vittori’s looseness is viable, but surely someone with greater visual imagination would have been more suitable. Her pages are simple portraits without grace or feeling, almost always restricted to the minimum necessary to convey any explanation or scene, lacking depth and finished off with unsophisticated watercolours. The entire effect is as if her roughs have seen print rather than the finished art.

There’s surely a place for a graphic novel biography of the original Renaissance Man and his glorious achievements, but this comes nowhere near to doing either justice.