Review by Ian Keogh

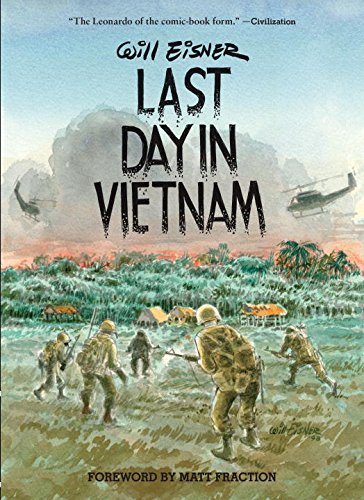

Between the end of his Spirit newspaper strip in 1952 and his triumphant return with A Contract With God in 1978, Will Eisner was all-but invisible to the comics reading audience. Not that he was out of work. For much of that time he produced PS, The Preventative Maintenance Monthly, a specialist magazine for Army personnel, and the work occasionally resulted in a trip overseas to where American troops were stationed. Five of the six stories stem from those journeys.

It’s the title story that’s the longest, clocking in at 27 pages, and cleverly told by Eisner as if it was what he was seeing at the time. The focus, though, is his guide, the person down to his final day’s service and on easy duties to give him the best possible chance of returning home. The introductory pages are mundane, characterising a seemingly genial serviceman, albeit one who considers the solution to the Vietnam war would be to nuke Hanoi. Turns out, though, that his last day is about to become more eventful.

The remaining material equally drops into the category of character study. The two Vietnam tales are of grief, then resentment, and Eisner’s on home territory, letting his expressive cartooning take the weight. One is silent, and the dialogue in the other is barely necessary, a distraction from the artistic focus. In Korea we meet a coarse and frustrated combat veteran who terrifies his colleagues, and a country boy who draws no distinction between shooting birds back in West Virginia and civilians in Korea.

Eisner’s World War II service provides the final and most affecting story about a soldier in his admin unit that gets drunk every weekend and types out and submits a transfer request he’s forgotten by Monday morning. The conclusion to this illustrated anecdote is perhaps predictable, but beautifully pitched, with a Gene Autry cowboy song playing in the background.

As always, the way in which Eisner’s laid out his strips is interesting. His loose cartooning is as deft as ever, but he’s approached many of the strips in an experimental fashion, for starters producing them all on canvas rather than paper, deliberately incorporating the rough surface into the mood, and electing to print on sepia paper stock. His mastery of movement is absolute, his soldiers all in motion whether upright or seated. The drunk in the final strip is swaying and stumbling, the combat vet a veritable hulk, and the injured soldier a contemplative sucker. You know these people without words explaining them.

In terms of content this is the slimmest of Eisner’s graphic novels, yet nevertheless an artistic masterclass. On the back cover Scott McCloud refers to Eisner as the heart and mind of American comics, and that’s the truth.