Review by Karl Verhoven

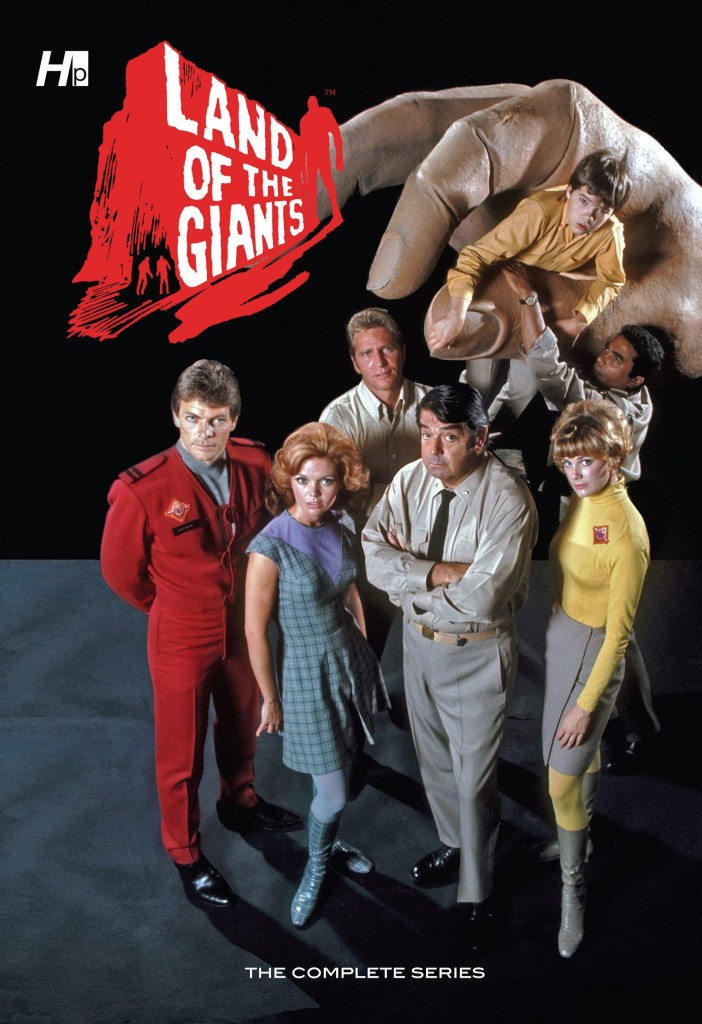

Land of the Giants was prime time family TV entertainment between 1968 and 1970. The show reworking the most popular segment of Gulliver’s Travels was dependent on the wonder of state of the art technology (and large props) to convince seven normal humans were interacting with people twelve times their size. Seen in our terms, the primary cast were six inches tall, and plot technobabble resulted in their arrival on the planet almost exactly like ours, but with everyone scaled up. Their perpetual quest was to source technology enabling them return home while simultaneously avoiding capture. It’s not dated well, and even the introduction to this collection of five comics published during the show’s run doesn’t claim its anything more than “fun” these days. So what about the comics that tied in with the show? Well…

They were written by Paul S. Newman, a man whose prodigious output ranks him a serious contender for having written more published comic scripts than anyone else to this day. If it was published by Gold Key in the 1960s, the chances are that Newman wrote it. The downside of this prolific work rate is a base level competence for comics aimed at children in the 1960s. There were no pretensions of an adult audience, and the plots override consistency. If a character able to hide in a cigarette packet in one tale is taller than a clenched hand in the next, so be it. Furthermore attitudes toward women are positively prehistoric with the male cast not giving them any credit for fundamental competence. When considering a friend of hers trained falcons, so she might be able to replicate the process with their enormous equivalents Valerie is grabbed by the shoulders and screamed at “Can you do it Valerie? Think! Forget your jet-set foolishness!”

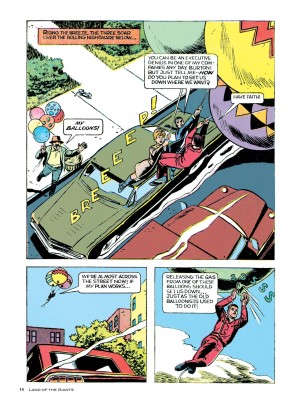

Artist Tom Gill’s brief was to ground the cartooning in a base level of reality. The introduction quotes him having to ensure the horses looked like horses and the people looked like people. He does rather better than that. A veteran strip illustrator, he knows how to pull the most from a script, and while clarity is paramount, there’s also a sense of dynamism about his art. Gill is credited with all art by Hermes, but the fourth issue is the work of a different artist whose sense of composition is far inferior to Gill’s.

Newman’s scripts provide opportunities for scenes too expensive for the TV show such as the sample art of Betty, Mark and Steve travelling by balloon, and this is the emphasis throughout, with the danger providing the tension and wonder. For all that, the best story relies on a greater exploitation of emotion, with Valerie befriending a giant who’s taken a wrong turn in life.

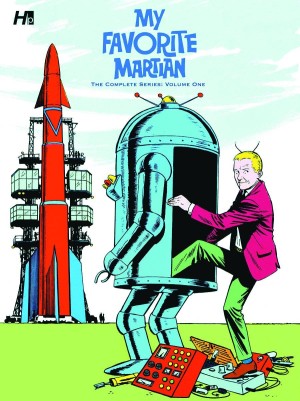

An extensive selection of contemporary promotional stills and associated merchandise complete the book, even extending to a spread from the Mad magazine pastiche of the time. As with the similar treatment Hermes gave Gold Key’s My Favorite Martian and Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea series, it’s difficult to fathom there’s a large potential audience for children’s comics based on 1960s TV shows now hopelessly outdated. It renders the project an indulgence for the curious possessed of substantial disposable income, and the scholar. Caveat emptor.