Review by Graham Johnstone

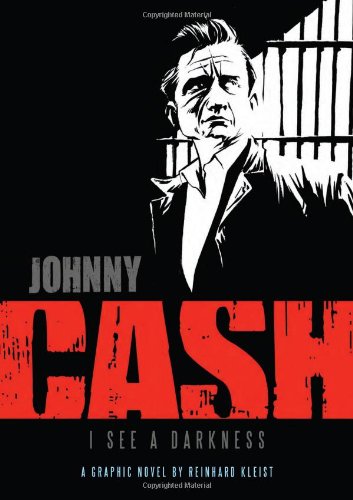

Johnny Cash grew up loving country music, and it became his way out of poverty. Teenaged Johnny left the family farm for opportunity in the city, played with Elvis, earned the admiration of Bob Dylan, and went on to sell millions of records. Reinhard Kleist shows all of this in his thorough biography. It’s no simple rags to riches story though, the title itself signals the inner struggles that dogged the self-styled ‘man in black’. This familiarity with struggle perhaps explains Cash’s lifelong empathy for those who never had the chances he did – exemplified by his song Folsom Prison Blues, which frames this book.

Cash played shows at Fulsom, and Kleist finds his angle in this – an inmate with his own song about the prison. When Glenn Sherley hears about the upcoming shows he tries to get a tape to Cash, and by way of explanation, tells his cell-mate Johnny’s story. This use of a storyteller acts as a disclaimer – this is not empirical truth, just what Sherley has picked up from newspapers and magazines. The main story ends as the show takes place. However, some loose ends are tied up in a coda with Johnny and production legend Rick Rubin at work on Cash’s acclaimed final recordings, including the Will Oldham song that provides the book’s title.

Before that, there’s a busy four decades packed into two hundred pages. Kleist keeps things moving at a brisk pace, though it would be welcome if he slowed down occasionally to convey the character reactions to key scenes. The human story is sometimes lost in the attention to factual details.

This density of content also means most pages are packed with small panels, which further reduces engagement and impact – CinemaScope it ain’t. Kleist’s sketchy brushwork is stylish, but sometimes fudges crucial signifiers like facial expressions. When he does allow himself more space, we get striking, iconic images – Johnny wielding his guitar, or kissing singing partner June Carter – but they’re typically more about visual impact than narrative or character moments. Some images surely come from press photos, but Kleist renders them seamlessly into his expressive style. He adds visual clarity with a single grey tone, that also evokes an era captured in monochrome, as well as the titular motif of darkness, and, (by implication) light. Kleist is clearly a skilled creator, though he seems constrained by biography – it’s when he steps away from the literal facts that the book really takes off.

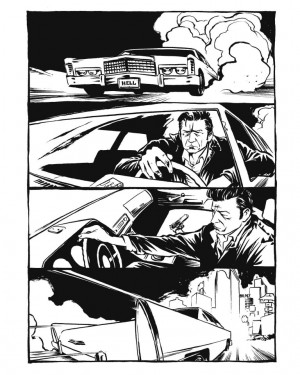

Look, for example, at the prologue – a classic American car hurtles past a neon sign announcing party city ‘Reno’, the driver looks like Cash. This is Johnny dropped into his song Folsom Prison Blues, so we see him shoot a man, and ‘watch him die!’ A few wordless pages later ‘Johnny’ is behind the bars of a prison bus. The car registration ‘HELL’ (pictured) is the only clue that this is a symbolic scene. Kleist weaves in other songs, like 1970’s hits A Boy Named Sue and One Piece at a Time, distinguishing them with a slightly more cartoony style. He further departs from literal truth for magic realist sequences at life or death moments – these have real visual power, but would have rung more true if foreshadowed through the book.

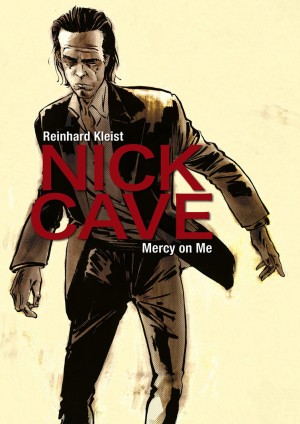

Cash is a fascinating subject – massively successful, but with personal struggles and liberal politics giving him ‘outsider’ appeal. I See a Darkness captures all this in a thorough biography, that really takes flight when it pushes the boundaries of the genre. Kleist would have the chance to take this approach further in Nick Cave – Mercy on Me.