Review by Ian Keogh

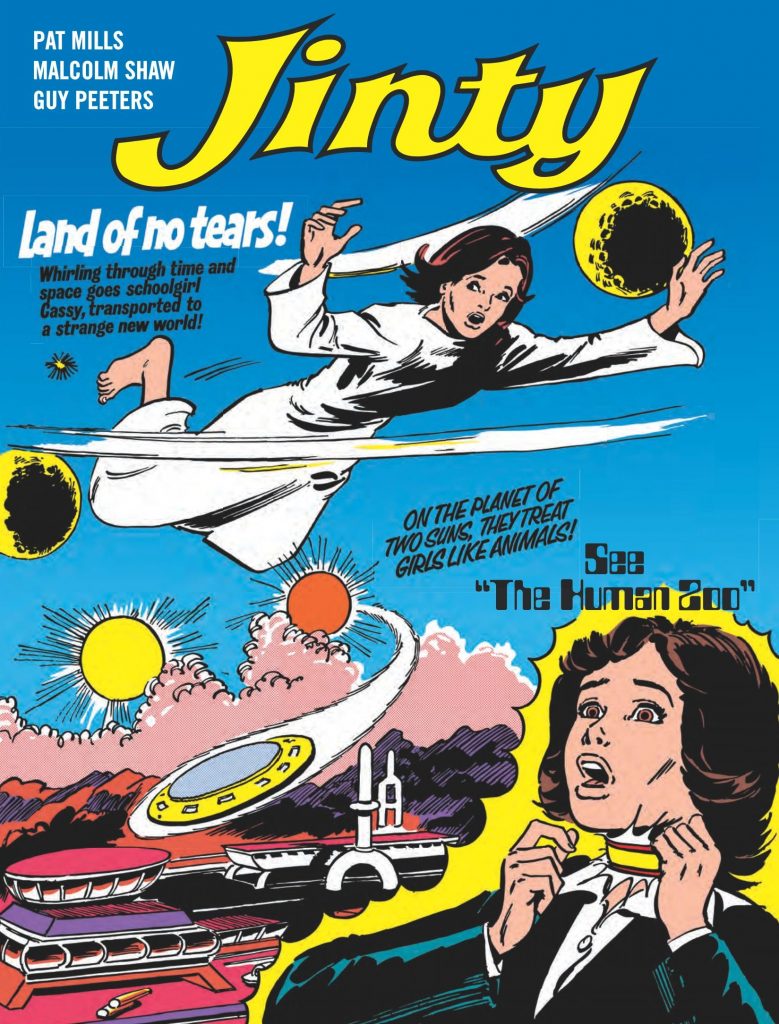

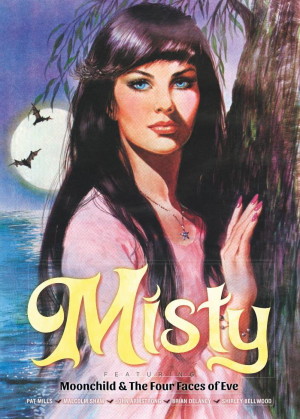

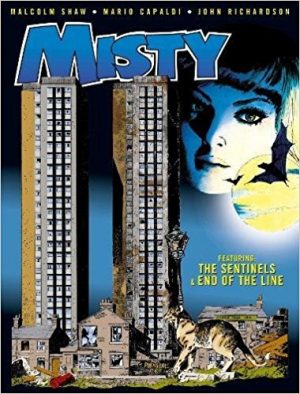

Following the pattern established by their Misty reprints, Jinty collects two originally serialised stories in black and white. While Misty prioritised horror drama, Jinty’s brief was a slight tinge of science fiction, and despite the reprints arriving later, was actually the earlier comic.

Pat Mills notes in his introduction that ‘Land of no Tears’ is his contribution most frequently remembered by people who talk with him about Jinty today. Originally serialised in 1977 and 1978, it also won a 1980 poll as the comic’s favourite story, earning a reprint, which at the time was in no way the publisher skimping on having to pay for new material.

Cassy Shaw was born with one leg shorter than the other, and Mills immediately marks his territory by having her exploit the condition for sympathy and favour, immediately setting her apart from the usual wholesome and unjustly set-upon heroines of girls’ drama strips. Her parents rather abruptly announce she’s to have an operation to solve her problem, and while under anaesthetic she finds herself transported to a very different world. Here everyone is the perfect physical specimen, emotions are forbidden, and children are raised from an early age to obey strictly enforced regulations. Mills’ introduction identifies channelling his Catholic upbringing into a hateful society where Cassy is subjected to all kinds of tortures and humiliations for being different, but her resourceful manipulative nature becomes a positive trait. It’s easy to see why this was such a popular read back in the 1970s. There’s almost a soundtrack of Mills’ gleeful sniggering as heaps the torments and cruelties on Cassy and her fellow “inferiors”, keeping the melodrama high and the problems coming in a society that’s stacked against them. Were it just parody, however, ‘Land of no Tears’ wouldn’t be as fondly remembered, and it’s the positive aspects that provide the strength, Cassy’s transformation into responsibility and the bonds of friendship.

Guy Peeters draws everything reprinted in this collection, his tidy style depicting young girls almost perpetually shocked or upset, reflecting the tragedies of the scripts. It’s very effective, but he’s not one for thinking about how clothing might deteriorate as it has to cope with dirty and wild conditions.

Shona is very sensitive to the predicaments of caged animals, considering it cruelty, while her sister Jenny scorns her attitudes. In a turning of the tables surprise, it’s an attitude Jenny comes to regret as the pair are abducted by aliens for display in ‘The Human Zoo’. Malcom Shaw’s plot piles on the parallels between the treatment of animals on Earth and the way the aliens consider humans no different from the zebras and camels they’ve collected for their zoo. Predicting 21st century dog collars outlawed in the UK, Jenny and Shona are fitted with devices imparting an electric shock for misbehaviour, and treated to cattle trucks, performing in pools and being kept as domestic pets. Shaw’s recasting of humans as animals is inventive and prompts the thoughts he intended, strangely strongest when Shona is released into the wild as an act of kindness, yet it proves to be an environment in which she can’t cope.

Both stories pile on the torment, and both stories have their moments of melodrama, as the writers’ mission was to drag readers to the next instalment in the following week’s comic. Within that, however, they both read well, with Mills’ less obvious parallels dating slightly better. ‘Fran From the Floods’ follows in 2019’s volume two.