Review by Woodrow Phoenix

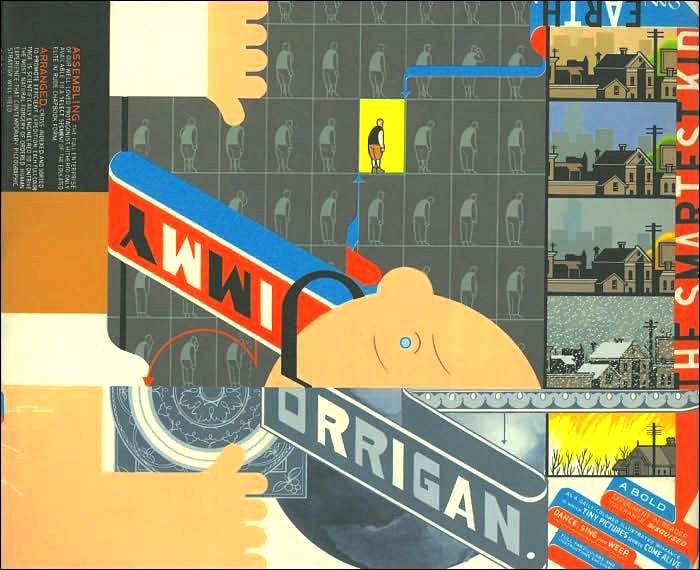

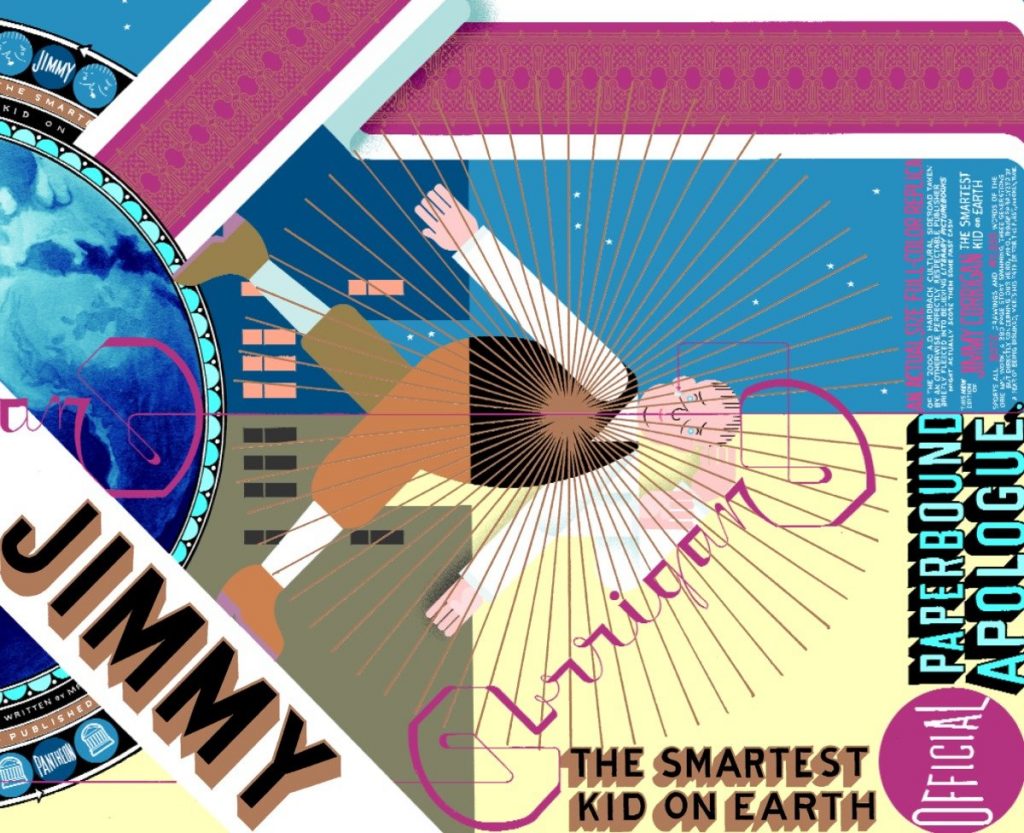

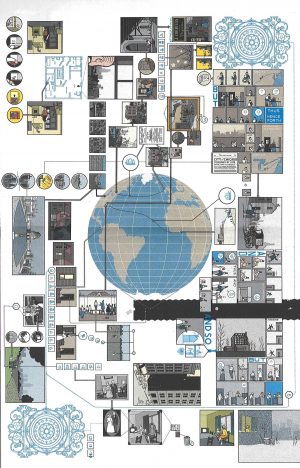

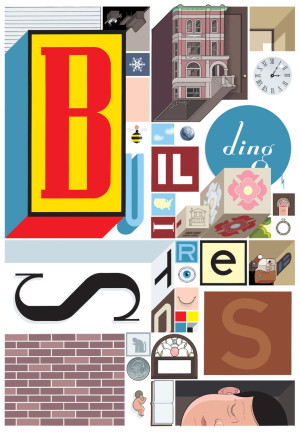

Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth is a hugely ambitious, hugely challenging, and at 380 multi-panelled pages, huge in stature piece of work. It uses its size, complex repeating structure and a seemingly endless supply of sub-textural asides, editorial commentary, teeny tiny marginalia and notes to demand a reader’s fullest attention in order to interact with it. The tremendous impact this book had on the literary establishment made Chris Ware the most celebrated graphic novelist since Art Spiegelman with Maus. Time magazine nominated Jimmy Corrigan one of the ten best English language graphic novels ever written. There is, then, no shortage of irony in the fact that although many thousands of people own a copy of this book a surprising number of them see no real need to read the whole thing, being satisfied merely to own this beautiful object and enjoy looking at the detail of its intricately crafted surfaces, the diagrams, cut-out models and dioramas to assemble, fake ads, charts, Victoriana, extravagant lettering and painstakingly rendered architectural backdrops.

Jimmy Corrigan immerses us in the near-unbearable life of the titular character, a lonely, socially-awkward middle-aged white North American man who lives alone and works in an anonymous office cubicle, with no friends and little meaningful human contact except a suffocating relationship with his overbearing mother. His main escape from this drab existence is fantasies that he is ‘The Smartest Kid on Earth’ admired by all, and best friends with Superman–or at least, Super-Man, an all-powerful, ultimate father figure who has a sinister barely hidden contempt for humanity. One day Jimmy is contacted by his absent father and he travels from Chicago to Waukosha, a small town in Michigan to meet him for the very first time. He also meets Amy, his father’s adopted African-American daughter. The narrative moves back and forth in time from the present to 1893 to show us Jimmy’s great-grandfather and his abusive relationship with Jimmy’s grandfather, which not only contextualises Jimmy’s doomed life via his dad but reveals the true nature of his familial ties to Amy, a more complicated bond than either of them can realise.

Jimmy Corrigan has deservedly won every comics accolade there is. It also won the Guardian First Book Award in 2001, the first graphic novel to be awarded a major British literary prize, causing poet Tom Paulin’s infamous snobbish meltdown on the BBC TV Newsnight Review show (“The colours are dreadful, it’s like looking at a bottle of Domestos or Harpic or Ajax. Awful bleak colours, revolting to look at, it’s on its way to the Oxfam shop”). If you actually do manage to read this complex and often infuriatingly cheerless book all the way to the end, unlike Paulin or any of his fellow critics then you should find your patience justified by this rigorous experiment in narrative. Ware’s use of comics’ historical antecedents, particularly Windsor McKay’s Little Nemo and Frank King’s Gasoline Alley filtered through 19th Century literary and advertising styles gives this work a detached formality which succeeds completely on its own terms.

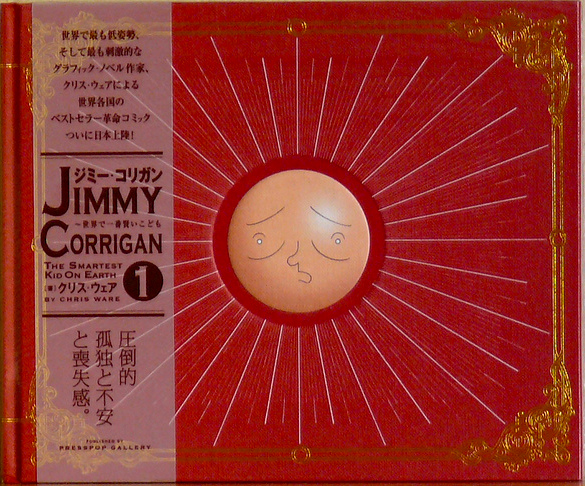

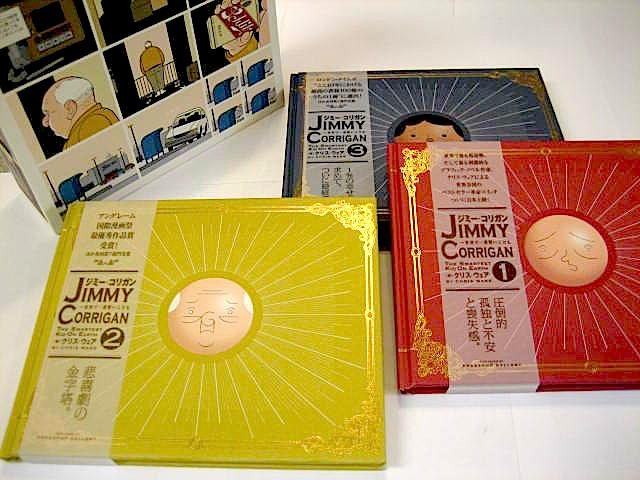

The hardcover and softcover versions of this book are very slightly different; Chris Ware’s ceaseless tinkering with form extends to the softcover version of Jimmy Corrigan having an extra couple of story pages featuring Amy. For collectors there was also a deluxe 3-volume hardcover set, housed in a slipcase designed and illustrated with a new comic strip by Ware, in a very limited edition of 300 copies from Japanese boutique publisher Presspop.