Review by Ian Keogh

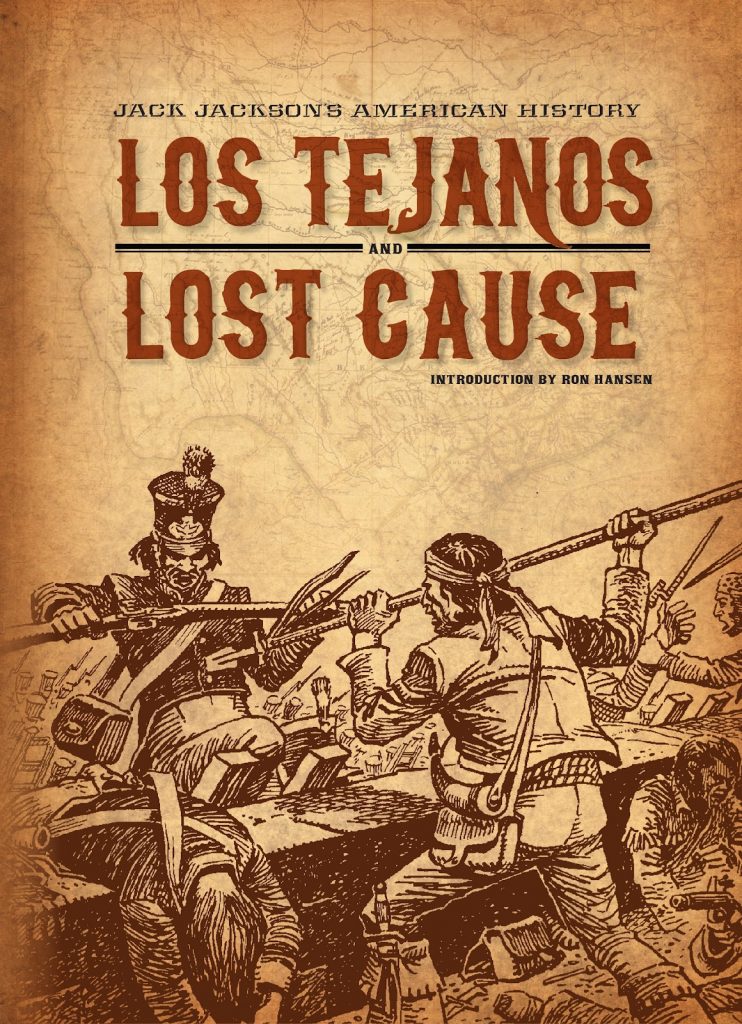

The late Jack Jackson’s influence is immense. There’s a clear case to be made for him as the founder of Underground Comix with his iconoclastic God Nose in 1964, while subsequent work highlights ecological and historical concerns, not sex and drugs. He was way ahead of the curve in producing deeply researched historical works from the 1970s, and Los Tejanos has its own place in history as among the earliest, if not the first graphic novels published by Fantagraphics.

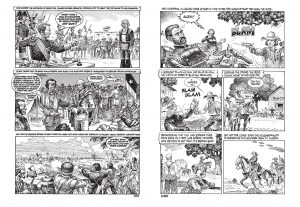

This 2013 edition combines Los Tejanos with Lost Cause, published sixteen years later, the difference in Jackson’s art evident on the sample spread. His is an obviously work-intensive style in either form, but the 1990s pages are slightly looser.

Jackson’s research was carried out in the pre-internet era, and both books are labours of love that had Jackson consulting library records for unpublished material, and eventually concluding there’s as much truth to folklore as there is to historical fact. That, after all, is written by the winners. For a short while Juan Seguin was among those winners, but his influence was gradually eroded, and when a century after the events Jackson published Los Tejanos, Seguin’s significant part in severing Texas from Mexico had almost vanished from history. The second tale concerns the background to and explaining of a long-running feud that blighted South Texas in the 1870s and 1880s. Due to the publication of his autobiography, John Wesley Hardin is among the most famous 19th century gunslingers, yet his beginnings were in the Taylor-Sutton feud.

Combined, both stories act as a history of Texas in the mid 19th century, starting when it was still Mexican territory in 1835, and ending sixty years later with the death of Hardin. Jackson uncovered large amounts of material never previously connected, and the result is a density almost unknown in comics. Students of Texan history will find both works invaluable as social life and work habits are diligently acknowledged alongside tumultuous events and politics, building a comprehensive history of the times in complex, skilled illustrations. However, especially with Lost Cause, Jackson’s concern with presenting every facet leads to him being unable to convey the essence. With the net spread so wide encompassing so many minor players, readers will have difficulty remembering who people are and their earlier relevance. Plenty of characters also populate Los Tejanos, but it’s easier to follow as the concentration is on Seguin and his activities.

Jackson provides introductions and afterwords addressing some topics, one of increasing note being his choice to use the language of the times when it comes to derogatory terms applied to African-Americans. It will offend some people, but is essential when Jackson tells part of his stories through occasionally awkward dialogue from people who’d laugh at the idea of tolerance. Avoidance would challenge the overall accuracy. The hardcover ends with Jackson interviewed by editor Gary Groth, who also supplies an introduction.

Finally, misgivings notwithstanding, Jackson’s work potently underlines the still not entirely recognised potential of comics to present scholarly studies.