Review by Graham Johnstone

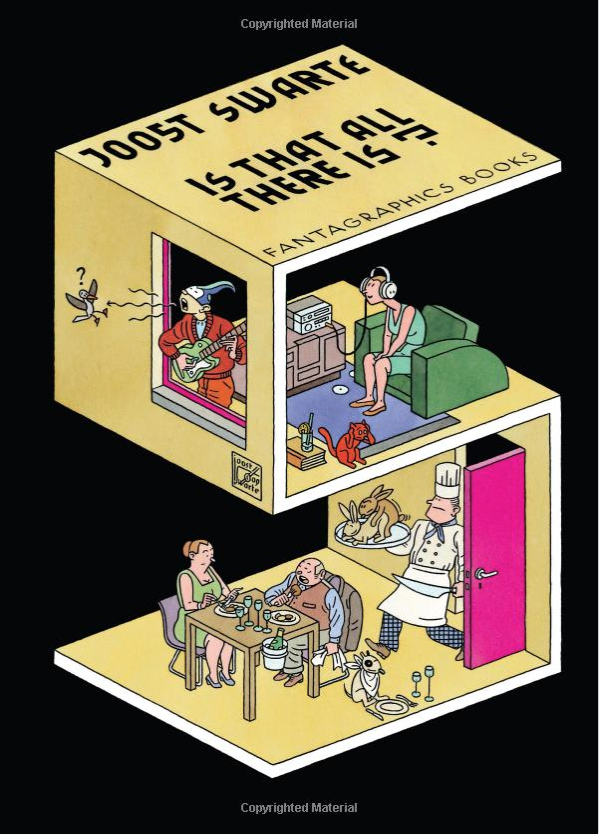

Transferring the title of the laconic Leiber and Stoller song made famous by Peggy Lee, to cover the relatively small comics oeuvre of Joost Swarte is an apt reference. The original Dutch title translates as Nearly Complete.

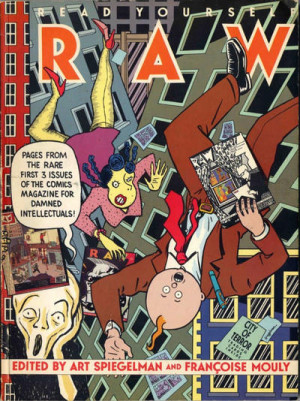

Swarte is more famous in his native Netherlands for his comics for children (Katoen en Pinball), and his other artistic work: his graphics, illustration, and prints, and has been knighted for his cultural contributions. He even designed the theatre building in his home town of Haarlem. In the English speaking world though, his appreciation lies in strips that appeared in Raw. Almost everything here from 1980 onwards appeared there or in Little Lit, also edited by Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly.

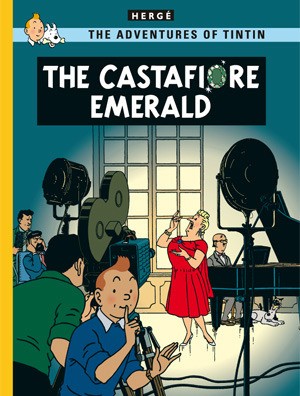

Swarte is credited with coining the term ‘ligne claire’ (in English, ‘clear line’), to describe drawing inked in an even line, without modelling or hatching. It’s most famously used by Tintin creator Hergé. Chris Ware, in his introduction, says that when he first saw Swarte’s work he mistook it for Hergé, but Swarte actually takes the style further.

A useful comparison is the painter Roy Lichtenstein – who (controversially!) took images from comics and turned them into works of near abstract formal beauty. Swarte does something similar – taking from Hergé, not single images, but his style, and refining and formalising it.

Swarte’s stories too are reminiscent of Hergé, but super-concentrated – distilled to the point of hilarious absurdity. Take the opener here ‘One Chance in a Hundred Thousand’ – its eight pages involve a tax dodge, a pretend kidnap, and a change of plan halfway through. It’s ostensibly a story of Jopo de Pojo, a dissolute musician, and free spirit. Unlike the pro-active, heroic Tintin, Jopo, here and in the longer ‘Imago Modern’, is a hapless victim of others’ agendas.

Swarte differs from Hergé in his relationship and attitude to the material. Hergé is involved and sincere: Swarte distanced and ironic. Even in ‘Enslaved by the Needle’ penned by countryman Willem, we’re less involved with the tragic (yet comically depicted) situations, than marvelling at the wit and craft in its creation. Abstract painter Jackson Pollock when asked why he didn’t paint nature said “I am nature!” In other words – the real subject of the art is it’s own creation. Swarte sits in European traditions of absurdism, and physical humour – it makes sense when Ware tells us Swarte loves the films of Jacques Tati.

‘Exercises in Style’ refers to Raymond Queneau’s book in which he wrote the same scenario in 99 ways – later inspiring Matt Madden to do the same in comics. Swarte returns to Queneau’s original and effectively says: here it is in one style – mine!

The colouring is notable. The later stories are painted in transparent watercolour washes, similar once again to the look of Tintin. Others are created with deliberately visible mechanical dots, perhaps playing on Lichtenstein. ‘Anton Makassar in Color’ and its accompanying text piece explain the process used – creating colour separations on transparent film overlays.

The colour printing is good, but with such intricate artwork and typically four rows to a page it really deserves a larger format. Fantagraphics published newcomer Tim Hensley’s plainer ‘ligne clair’ work on Wally Gropius at 10″ by 12″, at the same time as printing this career retrospective of a major talent at half the size! It’s a baffling decision – perhaps they had to tie-in with European editions of the Swarte book. There’s also no information on where the stories first appeared, which might have provided useful context. Still, this is a long-overdue collection in English of a brilliant creator.