Review by Frank Plowright

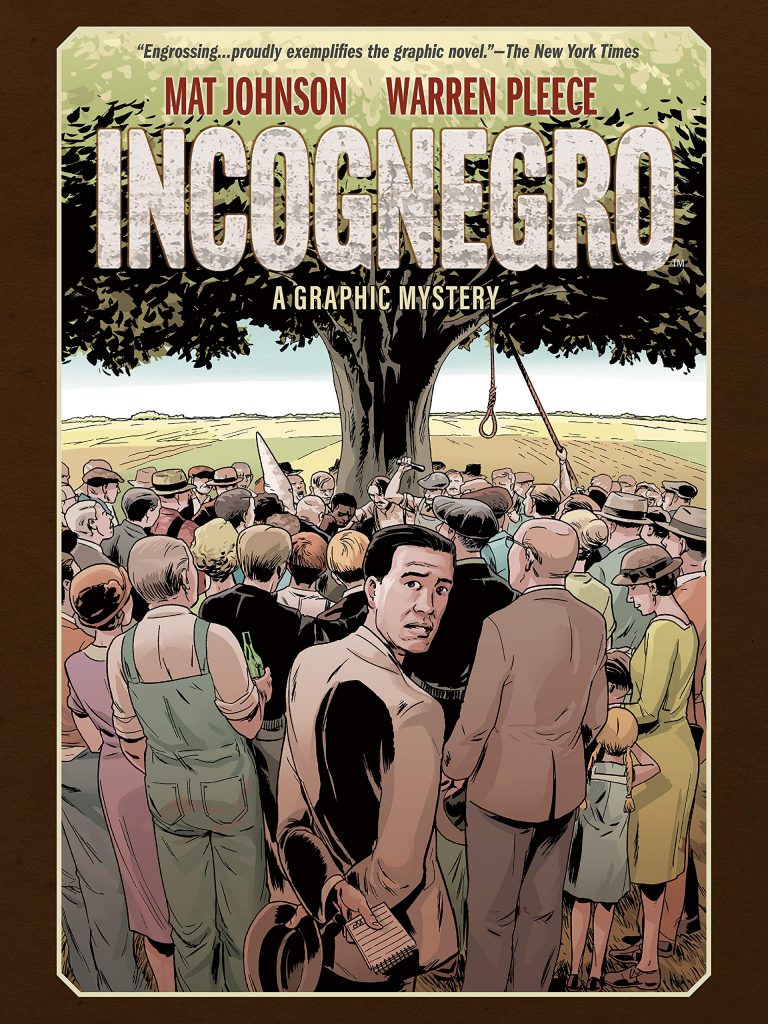

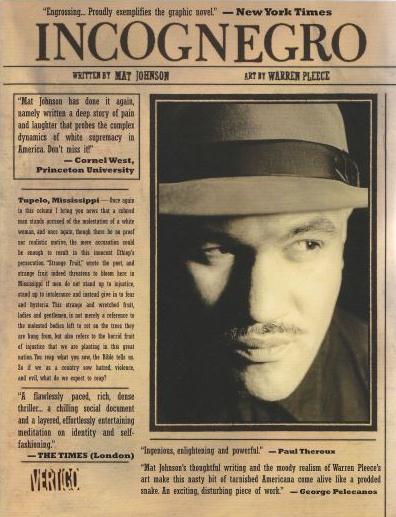

Incognegro begins with a horrific description of a lynching in the 1930s as undercover reporter Zane describes his journalistic techniques for naming and shaming those responsible. He’s the Incognegro of the title, the alias he uses for a New York paper reporting on atrocities, able to pass for white among the Southern rednecks, although sometimes having to make a fast escape. He also yearns to escape from the routine, to be recognised under his own name, but before that happens there’s one final case to take on, a guy arrested in Tupelo for murdering a white woman. Zane’s editor is confident he’ll take it.

Mat Johnson’s writing career is broad based, mixing fiction and non-fiction, and while Incognegro was his first graphic novel, his writing skills are eminently transferable from earlier work, and there’s no hint of being unable to adapt to the form. He knows how to write visually, and for the most part also knows when to let Warren Pleece tell the story. Pleece defines the period and the locations superbly, and his storytelling is first rate, but he’s not the most expressive of artists, and once the revelations begin flowing the stiffness of his art lacks the weight of emotional impact on occasion.

It’s worth noting that Incogengro’s inspiration was partly childhood games Johnson played with his brother, but also inspired by Walter Francis White, who actually did risk his life to expose racist murderers. The subtitle of ‘A Graphic Mystery’ is important, because once he’s suckered us in via outrage Johnson has a captivating crime story to tell. Alfonso Pinchbeck has been arrested for the murder of a white woman Michaela Mathers, and more so than usual Zane has a personal stake in the events. He’s accompanied down South by his mate Carl, less able to keep himself contained at offensive language and altogether more liable to draw to attention to himself. Will he prove to be useful or unwanted handicap? Zane also has unknown trouble heading his way, having used a ruse once too often.

Johnson has a clever technique of showing something working in Zane’s favour then later reversing it. A good example is Zane getting by with the maxim that white folk see what they want to see, until it’s pointed out that it doesn’t just apply to him, and the wider permutations have consequences. He also takes a broader look at Southern standbys, moonshine, a preacher and hillbillies, and be warned that in order to look at appalling history realistically, Johnson has to freely use the offensive language of the times. A successful feeling of foreboding is cultivated, and any crime fiction reader knows it’ll be miraculous if everyone we’ve come to care about survives until the final page. Ten years after the original Vertigo publication this was reissued under the Berger Books imprint to coincide with Incognegro: Renaissance, so there’s a reassurance that the concept survives.

Johnson’s ending is clever, its revelation at first seeming contrived and not anything that will withstand investigation, but the clever aspect is that it doesn’t have to. His afterword reveals the original edition was well received, but many reviewers were unaware of the truths being told, which surprised him. That being the case, as racism increases throughout the Western world, the reissue is welcome.