Review by Frank Plowright

Every now and then a new tragedy bumps the problem of African refugees heading to Europe across the Mediterranean back into the headlines for a couple of days. There’ll be, much hand-wringing among politicians, many thoughts and prayers, and after a week or so the issue will be ignored again. The reasons Africans risk their lives are many and varied, but distil to inequality of global wealth, and there’s no political will to address that. Perhaps part of the problem is that the deaths at sea, even of children, are so depersonalised. We don’t know who the victims were, or what their lives were like, only that they hoped for something better. And of course, there’s the all purpose demonising term “illegal”, so ingrained in our consciousness that we don’t even consider how ridiculous it is any longer.

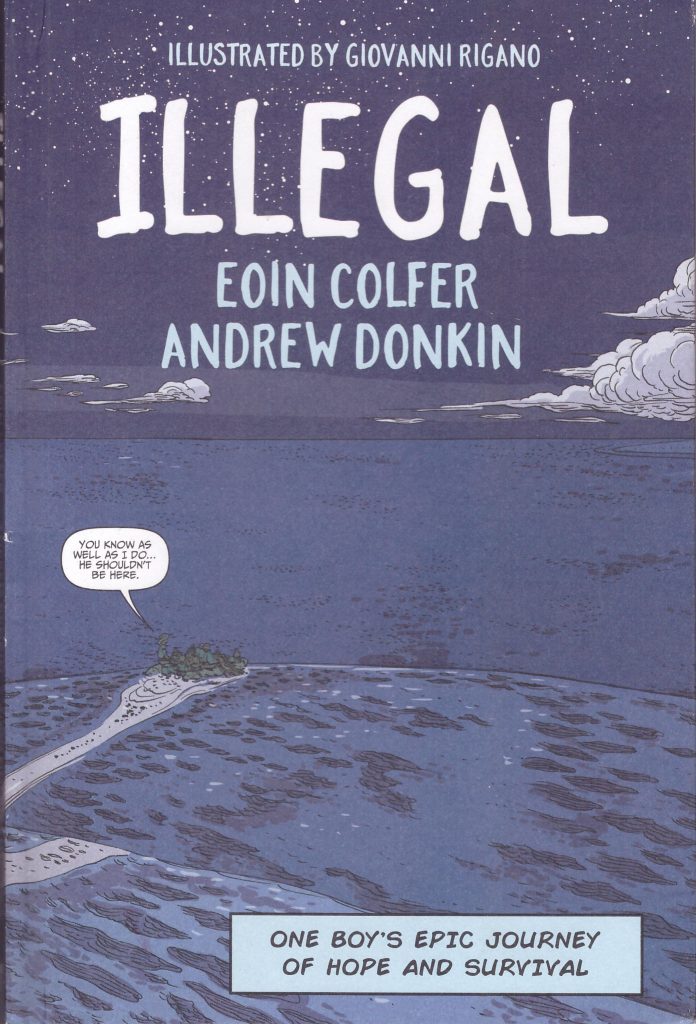

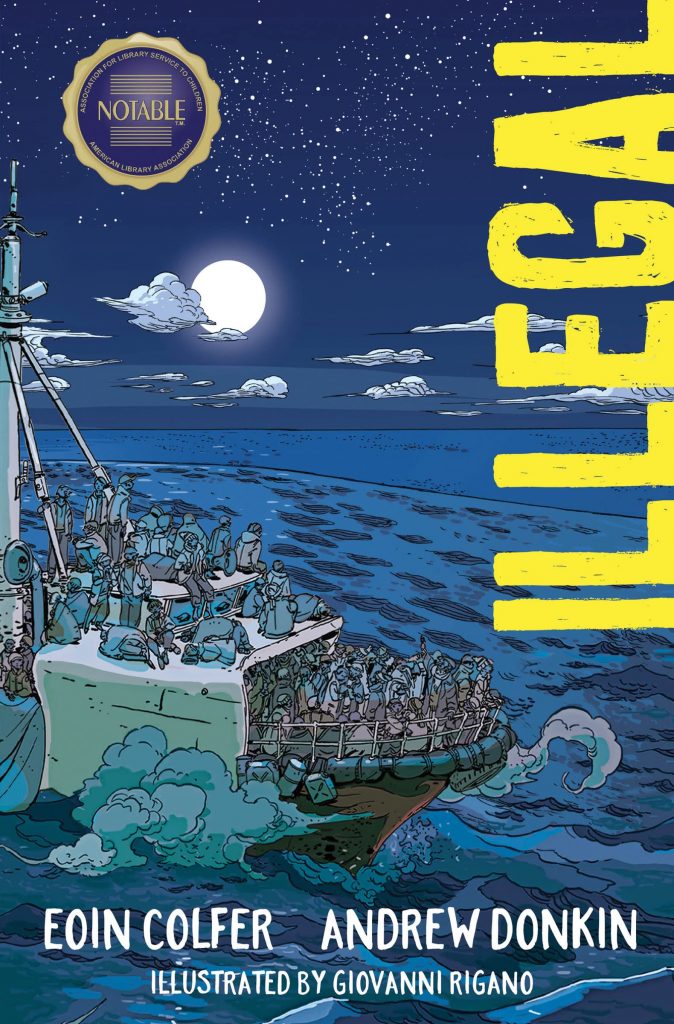

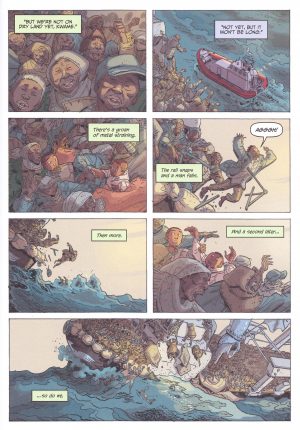

Illegal opens with a quote from Holocaust survivor (and Nobel Peace Prize winner) Elie Wiesel highlighting the notion of a human as illegal, before switching to Ebo, possibly twelve, in his African village. His is not a biographical story, but one incorporating the shared experiences of many Africans who’ve made the trip to Europe. We first meet him on a small inflatable dinghy on the Mediterranean with several others, and thereafter alternating chapters detail his journey to that point and his journey from it. He and others are exploited by predators every step of the way in Africa as Edo makes his way North to Tripoli. Water is confiscated, and then sold back at outrageous prices by traffickers crossing the desert, while others knowingly overload already unsafe boats. Eoin Colfer and Andrew Donkin ensure their story is harrowing and heartbreaking. Should there by any accusations of exaggeration, an extra four page story at the back details the experiences of Ethiopian Helen in her own words, and those experiences, if anything, are even worse than those of the fictional Ebo.

Giovanni Rigano employs some sympathy-inducing techniques in his art, such as big, wide eyes, but is otherwise very matter of fact in his depictions of squalor and victimisation, yet surprisingly detailed when it comes to vehicles. Edo has explanatory narrative captions and dialogue, so much of what he feels is down to Rigano, whose expressions and sense of movement are first rate, resulting in really evocative art.

Colfer and Donkin ensure there are lighter moments, as relentless misery would serve no-one, but in places this will be distressing for younger readers. Illegal does what it needs to do extremely well, and gives us all pause for thought.