Review by Woodrow Phoenix

Joe Ames and his wife are private detectives who come to the bland, suburban town of Ice Haven to investigate the disappearance of a child. There doesn’t appear to be a motive for anyone to kidnap quiet little David Goldberg. The kidnapper’s strangely written ransom note generates no leads and every conversation Mr Ames has with the people he questions around town distracts him with entirely different problems. This is not really a detective story. That’s just the motor that drives this tour through the lives of a group of dissatisfied, thwarted individuals, conducted by Daniel Clowes.

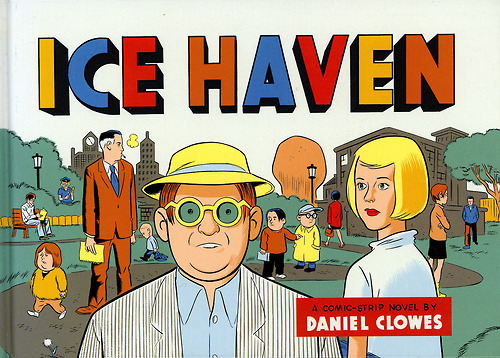

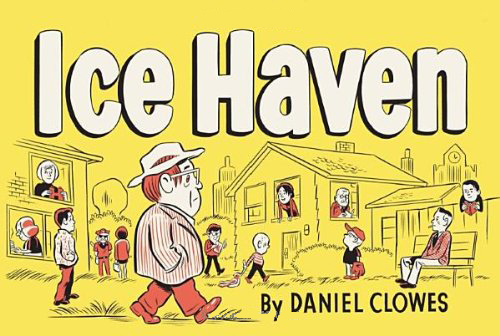

Ice Haven is presented as a group of interconnected comic strips. Each character is the star of their own strip, with a title header in distinctive lettering, and their story focusing on their secret sorrows and desires. Then each of them appears as supporting characters in other people’s stories, and the overlapping narratives gradually reveal the whole picture, although the reader has to do some work to piece everything together.

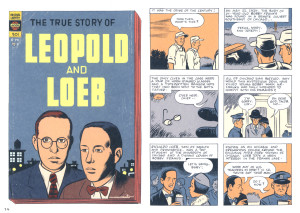

Random Wilder, an unsuccessful, procrastinating poet, is jealous of his neighour, Ice Haven’s poet laureate Ida Wentz, a woman with no discernible inner torments like him. Ida’s granddaughter, Vida, is a visitor to the town. She is an unpublished writer, and becomes interested in Mr Wilder’s poetry on finding some of it in her grandmother’s house. Charles, Carmichael, and Paula are three children in school with the kidnapped boy, David Goldberg. Charles is secretly in love with his step-sister Violet. Carmichael is a little bully who taunts Charles, saying he has killed David and thrown his body in a hole. He gives Charles a book about murderers Leopold and Loeb, which makes Charles think it may be true. Violet is desperate to leave Ice Haven to be with Penrod, who is in college in another town. The stories of all these and other characters intertwine and affect each other in the manner of a 1950s small-town soap opera such as Peyton Place, with nobody able to see how they appear to the people around them or realise their effect on the whole community.

Daniel Clowes’ work always deals with comics as a medium, but this book is more self-reflexive than any he’s created so far. ‘Comics critic’ Harry Naybors is a self-aware version of the narrator from Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, introducing Ice Haven by reminding you it’s a construction, and at the end, pointing out details as if for a book club (“as always, it behooves the critic to examine the intimate details of the author’s life and to strip-mine his body of work for evidence of thematic continuity, et cetera.”) When he questions Harry Naybors, even detective Ames gets in on the act, asking him somewhat rhetorically: “If a comic book is presumed to be ‘art’, then can’t we also presume that it is also made up of qualities inherent to its chosen form, qualities that by definition, defy verbal description? Isn’t it incredibly pompous to presume to quantify in words something that is intrinsically beyond the range of words?”

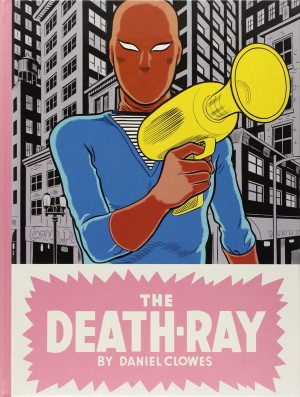

Ice Haven is a beautifully presented book, the landscape colour pages are charming, and the clash of those warm, slightly retro visuals with the cold subject matter works really well. The jigsaw structure of this book is a brilliantly intriguing way to present a story, but also a distancing device. Some readers may find it hard to care about anything contained here, but if you enjoyed Ghost World or The Death-Ray then you will like this.