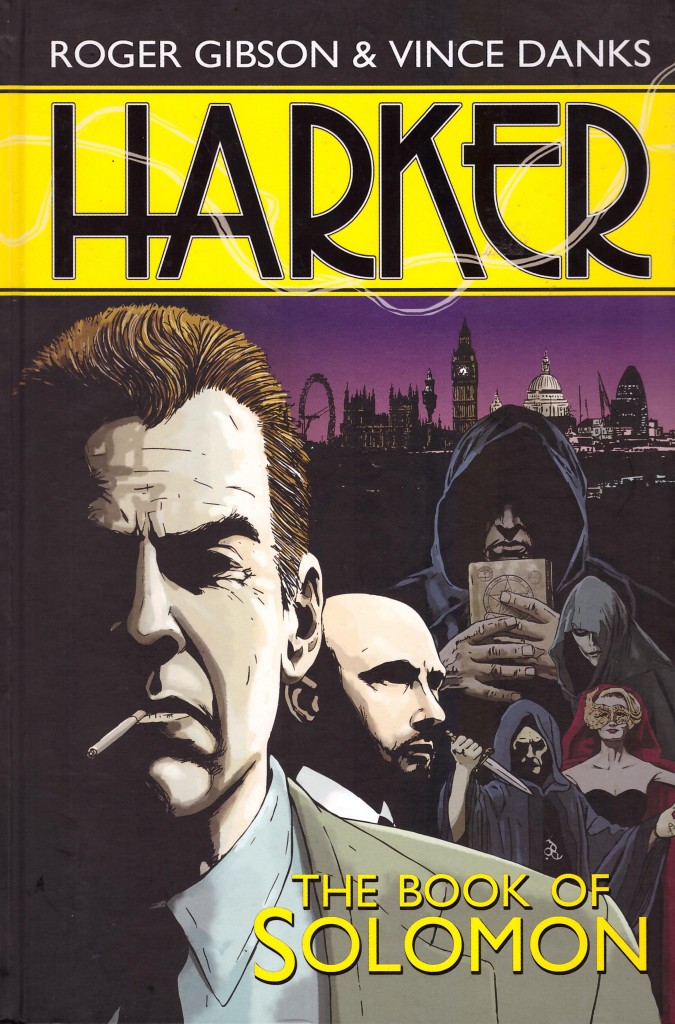

Review by Frank Plowright

Inspector Harker and DS Critchley are two unconventional police detectives allocated a case of what seems to be ritual murder, with the corpse laid out very publicly on the steps of a London church. Critchley is smug and arrogant, while Harker is more considered, but never quite knowable, which may be intentional, but is a risky game with the character after whom your graphic novel is titled.

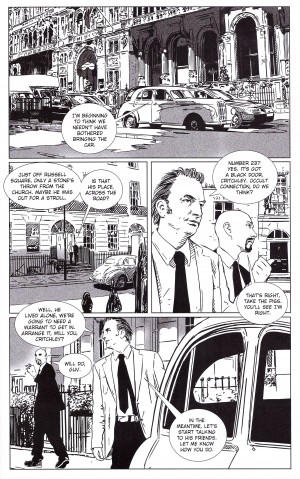

Vince Danks moves the story along very capably, although relies very heavily on image reference. This results in welcome pages of scenery showcasing the attractions of London and simultaneously establishing it as a location into which the cast are embedded. They’re also image referenced, and that’s problematical in places as they’re often stiffly posed. The good page design behind a long pub conversation is particularly affected. Critchley being presented as a fully bald man prompts the realisation how rare that is in graphic novels, and it helps to maintain a consistent look, but Danks finds doing so with Harker more troublesome, presumably based on who was posing for him for various pages. In places he resembles Doctor Who actor Peter Capaldi, at times author Roger Gibson, and on other pages neither.

As part of the creators’ attempts to ensure their story is resolutely English, The Sweeney’s Regan and Carter appear to be role models, their bantering style transferred to Harker and Critchley. Crucially, however, while their dialogue is on occasion clever and witty, it never comes across as anything other than words put into mouths, and as such fails to build them as rounded personalities. This matters because Harker and Critchley are the core of the book, between them carrying almost every scene. As far as the plot is concerned Gibson leads us on a merry chase. He involves satantic rituals, numerous suspects and varying motives, and the way Harker and Critchley piece everything together via persistence and analysis is the strongest aspect of The Book of Solomon. Also well handled is the contrast between the largely staid middle class lives led by many of the suspects supplemented by the modicum of excitement provided by playful indulgence in Satanism.

Although Danks is a decent artist, by the end of the book a viable question is what his purpose is. There’s very little in the way of staged action, so Harker and Critchley arrive at the scene of the crime and for most of the remaining hundred plus pages they’re either questioning suspects or talking to each other. It would work on the TV dramas Harker‘s obviously inspired by, but the lack of movement and variation on the printed page renders it just average. This being the case, perhaps a prose novel would have been a preferable option. A second Harker book titled Black Hound was initially promoted, but never published.