Review by François Peneaud

Post-catastrophe science-fiction tales are nothing new, but a post-catastrophe tale set on a generation ship? That sounds more intriguing, doesn’t it?

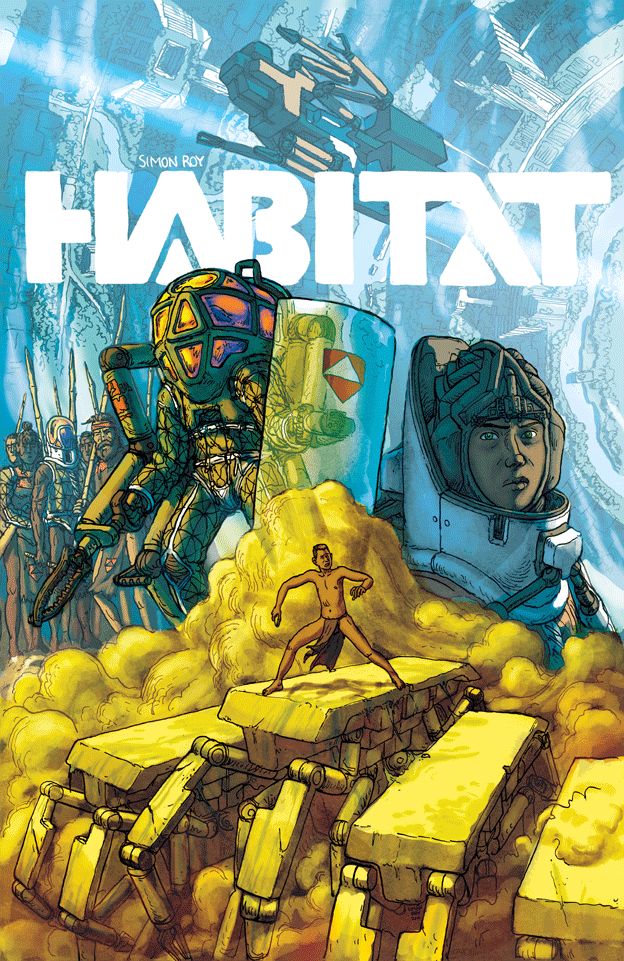

Hank Cho is a young man who’s being inducted into the Habsec, the security branch of a starship. Habsec men use circuit cards to command 3D printers to provide new weapons, and wear exoskeletons, but the weapons are mostly machetes and the men practice cannibalism (what are civilians here for, if not to provide sustenance?). That blend of future science and regressive social habits is the first striking aspect of Simon Roy’s Habitat, the seeming contradictions being built into the story as well as into the visual aspects of the graphic novel.

Cho finds himself right in the centre of the unending fight for power between the various factions of the ship, when he accidentally acquires a circuit card that doesn’t print a machete but a powerful hand-held laser, making its owner the most hunted person in that world. The narrative structure is classical: Cho flees his previous friends and allies, only to find a new friend in the shape of Joan, from the caste of the Engineers, the only ones with some knowledge of the workings of their common habitat. Cho and Joan flee the factions hunting them while trying to get to the heart of the machine and to the truth about the collapse of the civilisation of the ship, before the less well-intended factions put their hands on weapons that could destroy them all.

Roy’s artwork is neither in the style of the powerful, dynamic lines of the Jack Kirby, Neal Adams descendants nor of the elegant, pared-down tradition of Alex Toth. He’s somewhere around a dilapidated 1970s European SF aesthetics, a grungy Moebius, so to speak. He makes Habitat a visual feast. The giant, half-fallen buildings, built into the curved sides of the ship (think of something like this), look distinctly mesoamerican and are decorated with utopian frescoes, giving clues to the intentions of the original passengers of the ships. The vegetation that has invaded everything makes it less plausible scientifically speaking (how could a highly complex artificial environment survive that?), but it certainly makes for beautiful pages. These can be claustrophobic as well as panoramic: a lot of the action is set in small rooms, while other scenes show the full glory of the gigantic background.

The same is true about the situations the characters find themselves in. Extremely violent, blood-filled fights break out and Roy never shies away from showing the effects, while super-science inspires awe and reverence. The tension is palpable, since the characters (and the reader) never know whether a machete-slinging cannibal or a polite, spider-shaped robot is waiting at the next corner.

Habitat is a graphic novel that rewards multiple readings. Roy has managed to build a complete world without being heavy on its background, letting the reader gather clues and hints, all the while giving us a rich and fascinating spectacle with high stakes.