Review by Ian Keogh

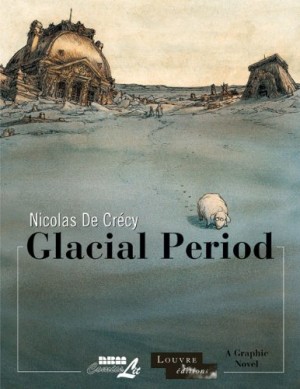

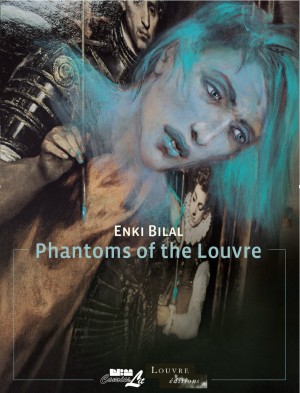

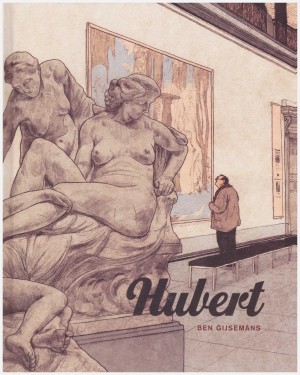

The Louvre’s commitment to graphic novels continues with this eighth publication commissioning a creator to build a story around the collection they hold.

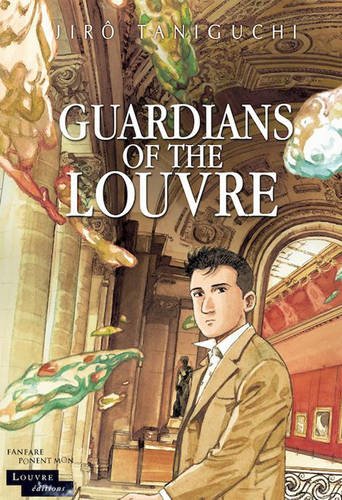

Jiro Taniguchi is the first non-European creator to contribute to the series, and is far more direct in his incorporation of the art as having a personal relevance, although the line is blurred. Is the comic artist who relates the story Taniguchi himself or a stand in? The visual representation is certainly the latter.

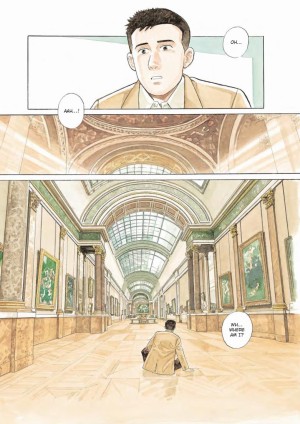

The protagonist stops in Paris after visiting European comic conventions, but is suffering from a fever, which cuts into his stay. He decides to maximise his time at the Louvre in preference to brief glimpses of Paris’ other wonders, and spend the remaining three days there. On the verge of collapse during his first visit, he discovers himself attuned to what’s described as the space between dream and reality in which the Guardians of the Louvre exist. These are the souls of the art stored at the museum and the visitor is able to traverse time himself in order to meet artists who’ve influenced him.

This transition is largely irrelevant, a mere wispy and surreal hook onto which the illustrative and historical investigation of the premises is hung, and that delivers an artistic treat, with Taniguchi reproducing dozens of paintings and statues amid the explanations of why they’re important to him and others. He deplores the box ticking mentality of jostling crowds focussing on the Mona Lisa while ignoring the other edifying delights on display, and the end result is elucidating and inspiring. Via himself and other voices Taniguchi muses on technique, appreciation, state of mind, preparation and the indefinable that fuse to create a great work of art. He deconstructs and educates, among other topics on the cross-pollination of approach via European painters of the 19th century who had a profound effect overseas. Despite a significant collection in the Louvre, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot is little known beyond art historians, yet has proved enormously influential on Japanese art. Taniguchi acknowledges his position in the chain of influence.

It’s not just the art that Taniguchi appreciates. He investigates a vast ventilation system every bit as imposing as the art in its own way, and also acknowledges the astonishing accomplishment of packaging and rapidly removing the treasures for protection from the Nazis (a topic that formed the basis of Kathryn and Stuart Immonen’s web comic Moving Pictures). This anecdotal-rich sequence recognises the achievement of Jacques Jaujard, without whom it’s likely much of what was displayed in the Louvre in 1940 would no longer be hosted there.

Just when you have Guardians of the Louvre pegged as a very entertaining and informative ramble, Taniguchi shifts gears with a heartbreaking sequence of intensely personal grief, which is purged via the spiritual connection with art. It comes across as rather stapled on, but what is art if not the purest appreciation of life?

Much of Guardians of the Louvre is wish fulfilment, but exuberant and enlightening, atmospheric and accessible. Anyone with an interest in classical art will find the purchase well rewarded.