Review by Frank Plowright

Possibly more so than any other DC headliner, compiling a 75 year overview of Green Lantern is a tricky proposition. Reasons for this include Green Lantern being a term that’s applied to at least five different humans, never mind thousands of aliens, and that many of the character’s defining moments have been far from popular. Two stories from Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams’ early 1970s work on the character are presented, and may be considered groundbreaking now, but at the time resulted in readers deserting Green Lantern in their hundreds of thousands and the comic’s cancellation. Replacing Hal Jordan, the most popular iteration, may have generated a short term sales spike, but the following changes to Jordan were widely reviled. His 1990s replacement Kyle Rayner is best remembered for the gross lapse in taste that prompted an entire campaigning website named Women in Refrigerators. Plus, there’s a stupid narrative convenience to the character only very recently addressed. Green Lantern’s ring can do anything the wearer wants, limited only by their willpower, except when encountering anything coloured yellow, against which it’s powerless. This updated the weakness of the original 1940s character who experienced the same problem, but with wood.

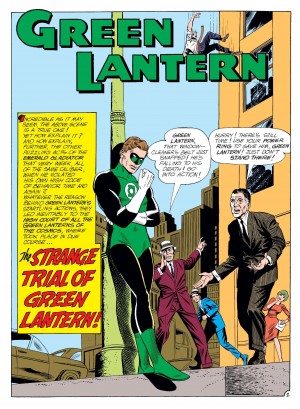

Martin Nodell created that original character, with Bill Finger scripting his adventures. Nodell and Paul Reinman’s art is basic by today’s standards, but there’s some wit about an Alfred Bester script in which the author intervenes in his characters’ lives. A 1940s Alex Toth strip isn’t what he’d become, but displays him as several notches above his predecessors on the talent scale.

Jordan first appeared in 1959, willingly accepting his role as a galactic cop, the structure of the strip reinforcing the wholesome faith in authority DC pedlled at the time. The 1960s material was ever better drawn by Gil Kane (sample art), and written by John Broome whose plots posed puzzles and solved them imaginatively. Their final story introduces Guy Gardner as Green Lantern, and O’Neil and Adams present the first appearance of John Stewart, the African-American Green Lantern. It’s hardly subtle, but the importance of this major breakthrough in social awareness from 1972 can’t be overstated and the graphic realism of Adams still impresses.

Overall there’s very little poor art. Mike Grell obviously enjoyed drawing the feature, and Joe Staton could now be seen as years ahead of his time, but had the misfortune to be a cartoonist when ‘realism’ was the prevailing aim. His storytelling’s first rate, as is that of then newcomer Kevin Maguire on a Justice League story strongly featuring the uncouth Gardner as Green Lantern. Later in the book Randy Green, Ethan Van Sciver and Doug Mahnke have different styles, but all work.

Given the controversy and what’s reprinted here, the 1990s wasn’t a golden era for Green Lantern, but the best content is the most recent, and that’s always a good sign for a character’s health. All three of the final stories are written by Geoff Johns, beginning with ‘Rebirth’, which as a series not only relaunched Hal Jordan as Green Lantern, but rectified in logical fashion the plotting mistakes of the recent past. The single standout, however, is Johns collaborating with Darwyn Cooke on ‘Flight’; a sentimental explanation of Hal Jordan’s desire to fly, beautifully observed and drawn. A final story again selecting a new human owner for a Green Lantern ring displays how far the feature has come since Hal Jordan called his Inuit assistant Pieface.

One can quibble about the stories selected – no Dave Gibbons? No Ivan Reis? – but it accurately and fittingly represents Green Lantern’s assorted incarnations over the decades.