Review by Frank Plowright

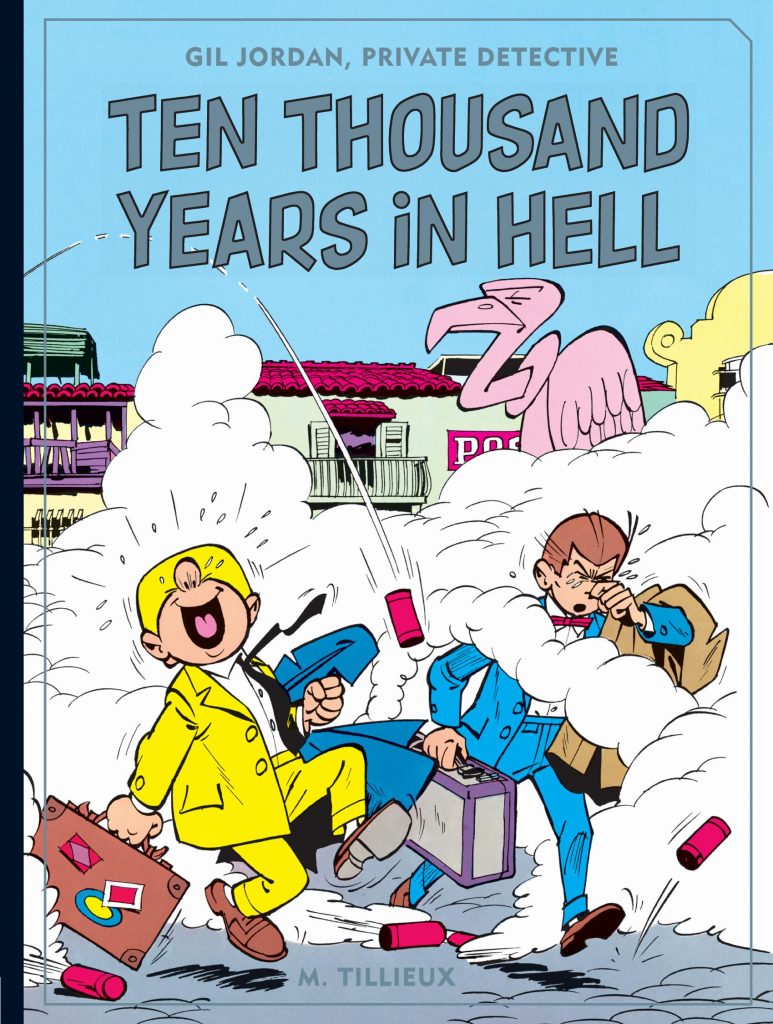

This second Fantagraphics translation of Maurice Tillieux’s Gil Jordan presents another two elegantly drawn crime adventures, first published as European albums in 1962 and 1963. Tillieux’s broad range of interests and research ensures the two stories are very different, both from each other and those seen in Murder by High Tide. This time round Jordan’s tasks are to investigate the kidnapping of an inventor in a South American dictatorship and to deliver a threatening letter to the correct addressee, and help them if possible.

Titling the first story Ten Thousand Years in Hell over-dramatises the content. The original French title would translate as Escape From Xique Xique, which is still mysterious, and nearer the truth. The ten thousand years refers to the sentence handed out to Jordan and his assistant Crackerjack in a kangaroo court, with Xique Xique the hellishly hot and seemingly inescapable prison where they’re to serve their time. It’s an exotic setting, pulling Jordan away from his French comfort zone, but he’s a determined planner whatever the circumstances. The delivery of the letter in the better titled Boom and Bust is complicated by severe weather conditions and the sideline of ordinary vans being stolen by the dozen in Paris.

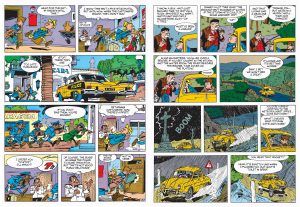

It’s extremely difficult to avoid comparisons between Gil Jordan and Tintin. Tillieux works primarily with the same light and shadow free style as Hergé, and is an equally good artist technically, wonderful at setting a scene. Tillieux’s happier with holding the same viewpoint for longer, is more subtle with colour and has a looser, sometimes more abstract way with people. He ensures every page looks fantastic, but while Jordan and Tintin are both investigators, in the early 1960s, even with a decent career already under his belt, Tillieux couldn’t match Hergé’s skilful plotting. Jordan’s adventures are relatively straightforward, don’t pack as much in and the gags lack some refinement. That said, almost any series would come second best to Hergé’s enviously tight plots, but both stories feature a lack of logic to the way some elements feed Tillieux’s plots. An example would be what the villains are up to in the second story, which is over-complicated with the timing of the dry runs too frequent and obvious, or the ease with which Jordan escapes the desert prison in the first. In both cases the flaws wouldn’t have been as glaring when the stories were serialised a few pages at a time.

There will have been a time when Tillieux’s art looked old fashioned, not helped by his love of drawing cars, which will always date a feature. However, class eventually sustains its value, and Tillieux’s pages can again be seen as extraordinarily well crafted in absolutely defining a period. His art develops still further over later Gil Jordan stories, and it’s to be hoped they’ll also one day be available in English.