Review by Frank Plowright

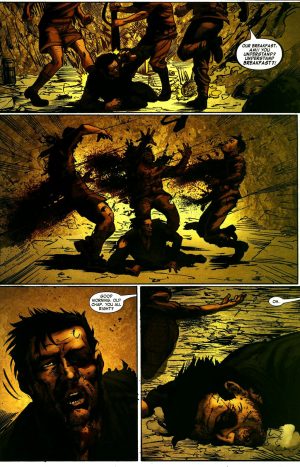

A relentlessly downbeat opening chapter has Nick Fury in Tunisia during World War II, contrasting the reality of life under fire with the jingoistic crap he and his unit were fed about the superiority of US armaments before the mission. It’s followed by the inevitable outcome of such pride, and Fury meeting a squad of British irregulars, tasked with deciding their own missions, but causing as much trouble as possible behind enemy lines. The unmentioned implication is that they’re the inspiration for Fury’s Howling Commandos, unseen in this story, where they’d be a distraction.

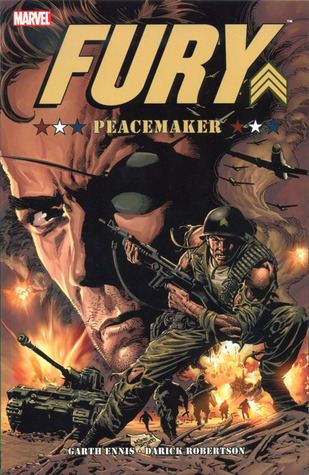

Creators Garth Ennis and Darick Robertson were just about to embark on their most successful collaboration The Boys, but already had one Fury project under their belt, a none too inspiring look at his later years running S.H.I.E.L.D. This is far more impressive. The cast may be fictional constructs, but for most combat sequences they’re operating in real areas where World War II battles occurred, and not just those involving allied troops. These are effectively laid out by Robertson, deliberately accentuating the horror of warfare along with the casual loss of life.

The opening two chapters are by way of setting the scene, introducing the cast, their priorities and their capabilities, and while necessary, aren’t as gripping as what follows when the story jumps forward to 1944 and takes a different turn. The central conundrum introduced is in effect a toss of the coin decision. One scenario could see World War II ended at a stroke, the other results in everyone’s death. Ennis perpetuates the suspense about whether or not the truth is being told until a big surprise finishing the penultimate chapter requires another change of tactic. Almost incidentally, it’s also the story of how Nick Fury, World War II battle hero, lost his left eye, revising the 1960s explanation.

Ennis bases some his primary characters loosely on real people, borrowing a considerable amount of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel for the career and experiences of a German strategist, and the detail his research provides regarding this and other matters cements the reality of Peacemaker. Beyond that there are some interesting sidelines, such as the comparison between English and German nobility, and the way experience moulds Fury. Robertson is good at laying out the pages and providing his own authenticity, but has trouble keeping the cast consistent from panel to panel, and in scenes where people aren’t wearing something distinctive identification can be tricky.

Anyone who enjoys a tense war story certainly won’t be disappointed with Peacemaker, but will have to work past the slower early section.