Review by Frank Plowright

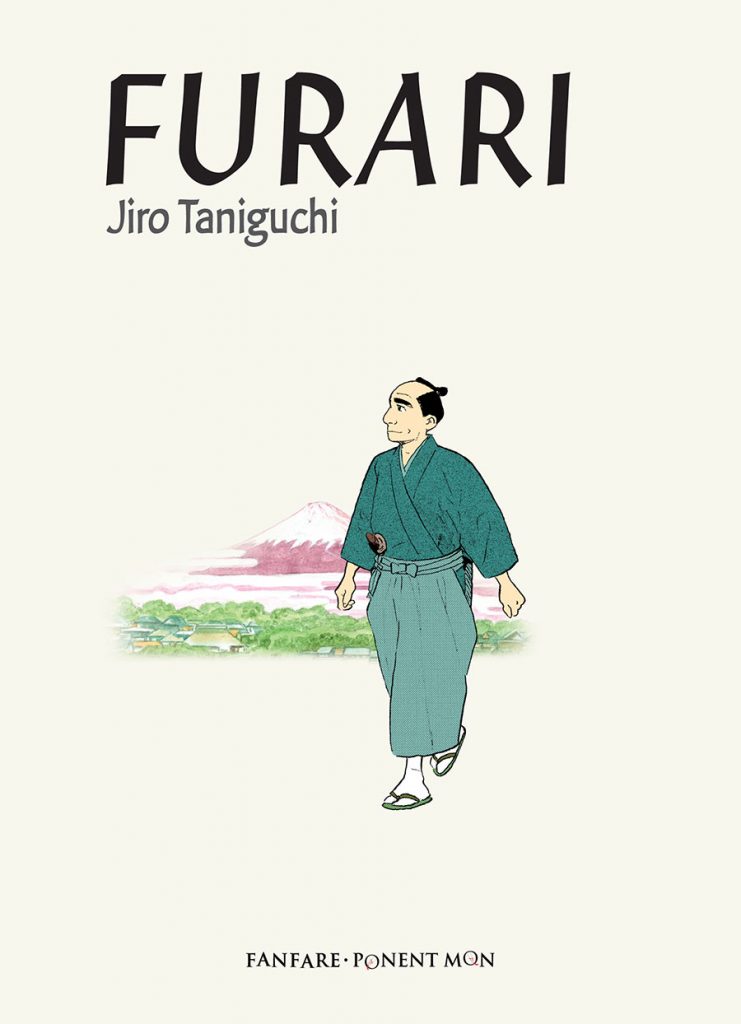

Furari flies in the face of most manga. To label it understated is barely scratching the surface. The only fight scene is a single panel disagreement between a tofu seller and dissatisfied customer, and there’s no comedy staging, nor alien or supernatural intrusions, just a profound calm beauty to every single page. English language comics provide no point of comparison to a series of chapters about a retired middle aged man ambling around Tokyo, known as Edo in the eighteenth century. He has an appreciative eye for the beauty of nature and craft, and is occasionally accompanied by his wife, but generally alone.

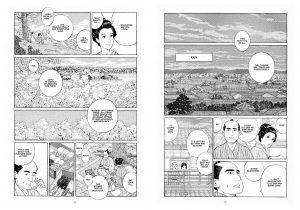

Jiro Taniguchi’s art is almost figuratively perfect, and the spell it casts is essential for the appreciation. A very refined ink line bestows a delicacy to the expressions of his cast, and nature is always beautifully depicted, be it landscape or wildlife, while Taniguchi’s work ethic is astounding, no detail too small for inclusion in order to present a convincing world. A bull slavers, the water ripples around a turtle released into the river, the crowd gathering fish at low tide all wear distinctive clothes, and every roof tile is shown on the sample image. This is all with a minimum of artistic shortcuts. His viewpoint is primarily that of the full figure, the surroundings completely filled in. Many artists specialising in detail have problems with movement, but Taniguchi’s man walks naturally, no stiffness about him, and the background characters, extras if you will, are always lively. There are a few colour pages, but Taniguchi works best in black and white.

The man followed is never named, yet Taniguchi strips back his poetic and dreamer’s nature, reveals him as a person prepared to follow where fate may lead. The Japanese title roughly translates as “Go With the Flow”, and that’s how to take the best from Furari. One chapter just concerns his tracking a cat through the town. He’s also resourceful, and has a sense of wonder to inform his observations. He notices a series of strange impressions in the ground during a walk, obviously tracks, and is informed a creature called an elephant passed by earlier. It’s a really smart piece of writing in which the elephant is never seen, yet it’s created via its residue and sounds, which can be heard across the city. We meet others along with our wanderer, a performing Sumo wrestler, a struggling poet, a storyteller, and people whose skills are more common, yet of interest.

Although the chapters are individual strolls, a continuity unites them, beginning with the man counting his paces. As the stories continue we learn his intention is to define a geographical distance of a single degree of latitude, an ambition requiring considerable calculation and accurate mapping of Edo. He regrets times when he’s become so captivated in a moment that he forgets to count, the tragedy of one chapter inspires him to invent a more accurate measuring device, and an interest in the angles of astronomy also informs.

Those familiar with Taniguchi’s work will recognise Furari as a companion piece to The Walking Man, in which a businessman saunters around modern Tokyo, and as with that it’s a work to be enjoyed a chapter or two at a time, an indulgence rather than a feast. An immersion too thorough breaks the spell. If you’re sensitive enough, the serene strolls and accompanying observations will have a calming effect, and how many graphic novels can honestly claim that?