Review by Frank Plowright

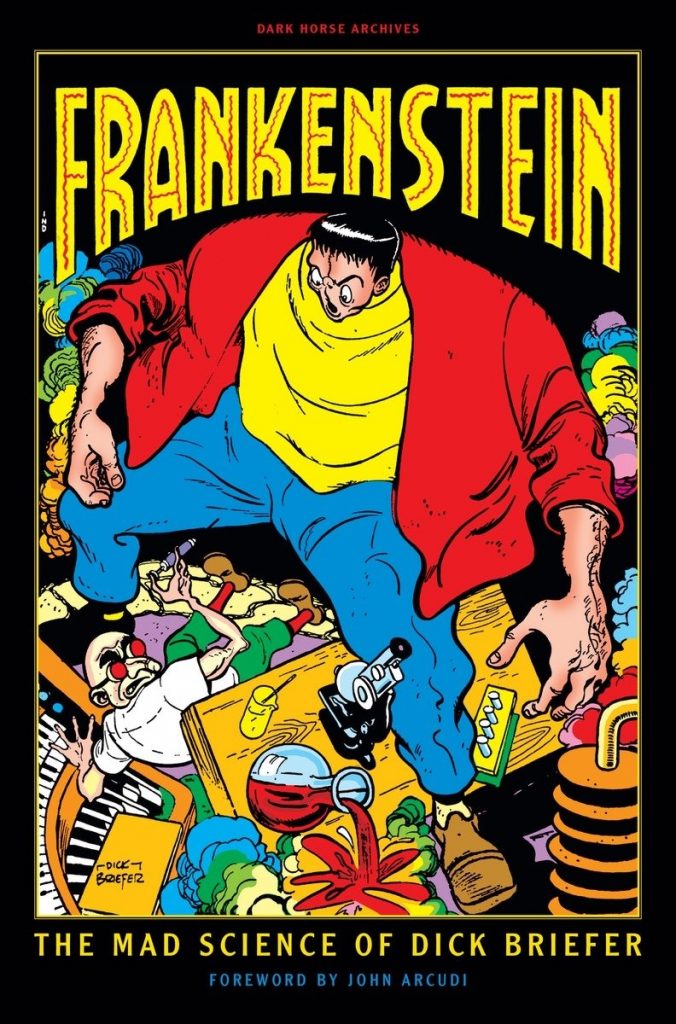

From the early 1940s to the mid-1950s, Dick Briefer spent most of his comics career drawing Frankenstein in one form or another. His first success was a horror version, but the most fondly remembered, and most sought after is his comedy Frankenstein from 1945. Before this collection it was only available to extremely rich or via the occasional inclusion in an anthology (The Toon Treasury of Children’s Classic Comics for one). There’s reason to be very grateful, therefore, for a three hundred page hardcover compiling 29 stories, every one of them madcap nonsense, and still very funny.

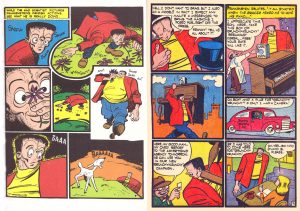

The reason is Briefer’s unique creative vision. It’s possible to skim Frankenstein and notice only the wonky design, what seems slapdash cartooning and places where characters almost bulge out of panels, but that’s all part of the comedy, Briefer almost presenting his creation as a shaky amateur production. The results benefit greatly from Briefer as writer often addressing the audience directly, to the point of listing those who complained about his Frankenstein Sinatra gag, and from what when studied is actually polished, farcical cartooning. Frankenstein’s nose being placed between his eyes, but above them, indicates the comedy instinct present throughout, and the rushed look actually becomes endearing through immersion.

Briefer may claim his is the only comic where not a punch is thrown, but he compensates by slotting the kind-hearted Frankenstein, protector of Mippyville into all sorts of gruesome comedy, some in gloriously poor taste. Yet on the other hand, he plays cards with vampires, helps out ghosts and is keen to see witches in productive employment. The lunacy of Briefer’s very individual plots even survive a précis. ‘Frankenstein’s Family’ has him reading in a newspaper that in America someone who starts as an office boy can become President. A trip to the White House confirms no vacancies there, so he starts as a junk collector for a mad scientist. Some technical jiggery pokery results in a machine that produces Frankenstein’s children, multiple miniature menaces who can be popped like balloons. The missing ingredient is a wife, who Frankenstein duly sources, a woman so overweight she’s unable to bend down and pick the children up, and on it goes. This is farce, but there’s a sophistication to the imagination, and most stories remain a delight.

Although not mentioned in the accompanying editorial material, the hands of other artists are evident on a few stories, with lopsided figures and less background detail. One appears to be signed by a Bill Joseph, and a Bruce Elliott is personally thanked by Briefer. Far better is early Archie artist Ed Goggin, credited as helping out for the final few stories. This may be for inking as Briefer’s loopy style remains much in evidence.

Briefer is a true maverick, his a conceptual mind almost beyond successful imitation in the manner of Robert Crumb, Harvey Kurtzman, Jack Kirby or Moebius. This good-natured iteration of Frankenstein is surreal and almost hallucinogenic, and these qualities ensure the strip still reads well in the 21st century, when almost any other comics from the era are only of historical interest.