Review by Frank Plowright

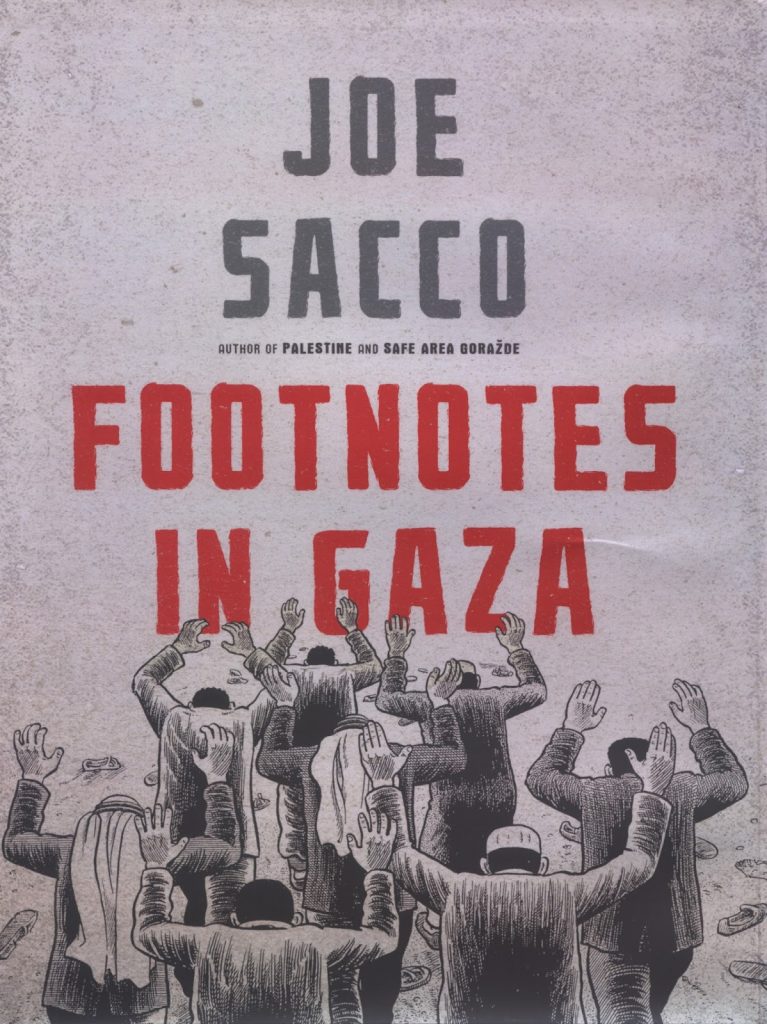

The end of 2023 is a disappointingly appropriate time to consider Footnotes in Gaza, Joe Sacco’s return to Palestine in 2002 to investigate a massacre that occurred in the city of Khan Younis in 1956. Sacco writes about it being the largest massacre of Palestinians on Palestinian soil, with 275 people killed, followed by another 111 deaths in Rafah a week later. This review is being written as Israel has ordered residents to evacuate Khan Younis in 2023, when well over 18,000 Palestinians have been killed during two months of Israeli attacks in response to a Hamas organised atrocity in which 1500 Israelis were murdered. It’s a tragedy without end, something Sacco notes in commenting reporters essentially file the same story again and again.

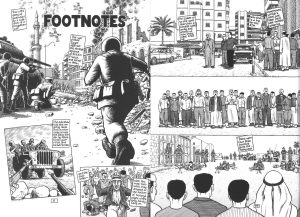

When Sacco began serialising Palestine in 1993 he was finding his way into reportage, a genre he almost single-handedly established in English language comics. 2009’s Footnotes in Gaza is the work of a veteran who knows how to sift his information for maximum impact. With experience comes an occasional cynicism not apparent in Palestine, but the haphazard nature has been superseded by a confident writer able to lead readers smoothly from one topic to the next, and quotes are attributed. The always busy and expansive art has also improved, Sacco no longer using experimental layouts and viewpoints, and every panel is bursting with life, or, sadly, death.

The events and concerns of 2002-2003 provide a constant reflection, but Sacco’s primary consideration is 1956, although his historical journey begins with Israel’s 1948 war with Egypt and the relocation of tens of thousands of Palestinians to Gaza, then controlled by Egypt. During the subsequent 1956 war with Egypt, Israel invaded Gaza, but this was preceded by a complex series of connected events that Sacco lays out with diligence and clarity. Yet he’s still able to provide his own views of those supplying the information, correcting their exaggerations with his own footnotes.

Sacco dispassionately records what people witnessed, but it ought to provoke outrage. Interviews with survivors corroborate a story of Israeli soldiers emptying houses, ignoring protestations that men weren’t fighters, lining them up against a wall and shooting them. A week later Palestinians in Rafah were instructed to head to the school building, Many were shot, and the survivors thoroughly battered. One has to admire Sacco’s fortitude in drawing several variations of atrocity. There are discrepancies in what he’s told, yet irrespective of the numbers possibly being a few less, someone claiming to be there who wasn’t, or Israel’s defence being there were combatants in the houses, the essential truth of a mass execution remains.

Truth is also a motivation in Sacco’s dealings with people. He’ll challenge views and dig to their foundations, yet the weight of barbarity recurs. Teenager Hani was shot seven times at close range for spraying a slogan on a wall. Houses are routinely bulldozed if Israeli soldiers claim the home has been used to fire on them, yet Israeli soldiers in a watchtower randomly fire into Palestinian homes. Reading what Sacco transcribes it’s easy to understand what the Israeli state seems incapable of taking in, that bursts of violence are the inevitable consequence of repression and subjugation.

Only brief moments move away from persecution and tragedy as a way of life, such as Sacco’s frustration at one source milking the attention for all it’s worth. However depressing it may be, though, Footnotes in Gaza is monumental journalism. And yet here we are in 2023 with nothing learned.