Review by Frank Plowright

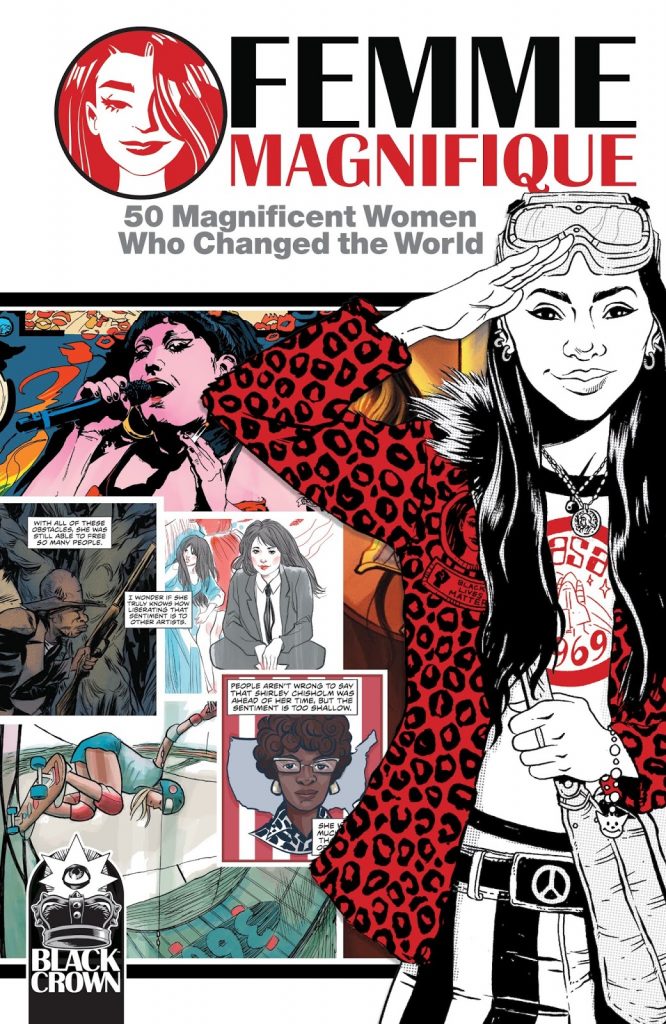

Fifty creators were teamed with fifty artists (if necessary) and allocated three pages to explain what it is that moves them about a woman they admire, each of these snippets preceded by a representative introductory quote. It’s a simple and effective formula covering some basics and so providing the basis for further research, and as might be expected, approaches vary considerably. The opening half dozen strips alone showcase both the variety and the centuries spanning inspiration. Tackling Kate Bush, Gail Simone and Marguerite Sauvage opt for montage with overlaid captions, while Maris Wicks spotlights Sylvia Earle via a first person narrative and cartooning, and the metaphorical placement of obstacles overcome is Kelly Sue DeConnick and Elsa Charretier’s take on Hillary Clinton. In between we’re told about pioneering newspaper writer Nellie Bly, 19th century fossil hunter Mary Anning, and 1960s NASA software developer Margaret Hamilton. Over the entire collection art meets science, lone voices shout into the wind and from dedication bravery erupts.

Some situations described infuriate in raising historical attitudes never properly rectified since. Mike Carey and Eugenia Koumaki write about Rosalind Franklin, who lived in a United Kingdom refusing admission to Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany without independent means and a sponsor. Betsy Houlton and Tyler Crook’s later piece on Ruth Klüger reveals the UK hardly acted alone. Karrie Fransman and Rob Davis spotlight abuse. Yet these are countered by so many situations where determination countered entrenched opposition. Some recollections are personal, such as Peter Gross charmingly recalling Laurie Anderson’s inspirational visit to the small Minnesota town where he attended college, or Brian Miller highlighting his archaeologist wife Kristy Miller. Whatever the circumstances, though, it’s an extremely rare strip that fails to inform or entertain, indicating solid editing and curation on the part of Shelley Bond

Is there a drawback? Possibly. This is a collection to be dipped into, a few pieces read at a time and considered, rather than a one-sitting experience, which is the common method of absorbing a graphic novel. Femme Magnifique possesses a density, so reading everything at once ensures not enough will be retained, which dilutes the possibilities, and if there’s a common thread to the women mentioned, it’s that none of them ever did that.

There is considerable crossover with Penelope Bagieu’s similarly themed Brazen, but reinforcing inspirational people is no bad thing. At only three pages per subject Femme Magnifique is more a primer than a definitive source, but surely no-one can read about the likes of Nellie Bly’s astounding life without wanting to learn more about her. Plenty of process material completes the book, including the opportunity for every reader to personalise their copy by filling three pages with their own story of an inspirational woman.

“Never be limited by other people’s limited imaginations” – Mae Jemison