Review by Frank Plowright

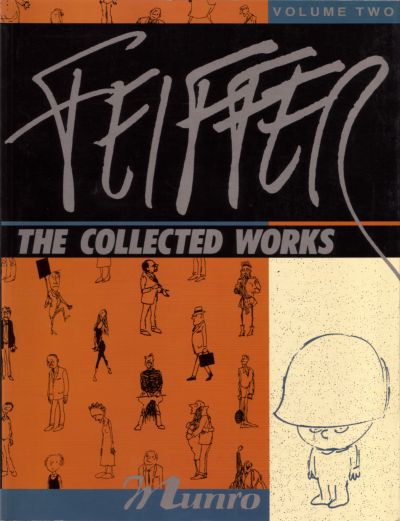

The policy followed for Feiffer: The Collected Works is to present Jules Feiffer’s creativity in chronological order rather than publication order, so ‘Munro’ provides the title strip as it was produced in 1953, Feiffer unsuccessful in selling it then as a drawn novella. It eventually became one of the other stories in Passionella and Other Stories, published in 1959 after the success of Sick, Sick, Sick.

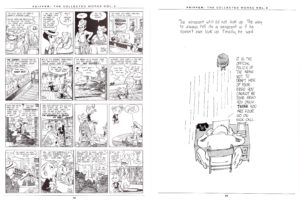

While ‘Munro’ forms the centrepiece, the collection includes other strips, and concludes with selections from Feiffer’s sketchbooks, other material also unpublished. Among that is the four week continuity prepared for a possible daily strip Kermit, about a runaway musical genius, touted around by Feiffer in 1950 when still employed by Will Eisner, and very much influenced by him. Consider how economical the style Feiffer’s known for is, then look at the busy, detailed left hand sample page. The premise isn’t the most commercial idea, but Feiffer compensates with some of the social observation that would later make his name.

Before Kermit we have the final nine single page Clifford gag strips, each of them nicely drawn, and well paced to a solid laugh at the end, Feiffer having perfected the form just before he stopped. In another world Feiffer never joined the army and Clifford became a much loved gag strip, eventually becoming a vehicle for his social commentary. That world, though, lacked Munro.

Feiffer never saw active service, lucky enough to avoid being shipped to Korea, but the bureaucracy, bullying and waste common to army life left a strong enough impression. The result was the scathing satire of a four year old boy drafted into military service. The central observation is that the military always does what best suits the military ideology even when that’s hypocritical or flies in the face of logic, as exemplified by the right sample page. Munro is funny and clever, but doesn’t have the subtlety of Feiffer’s subsequent work. Then, it was produced by an angry young man who’d just been discharged and felt he’d had two years of his life wasted. Despite the obvious nature, it’s a smart fable, and it’s all too easy to speculate that Feiffer’s failure to place it with a publisher had more to do with the US still sending troops to Korea than anything else. A few ‘Army Types’ cartoons later in the book repeat Feiffer’s sentiments.

Two further attempts at cracking the newspaper strip market were made after Feiffer’s discharge. Dopple is about a man attempting to prove the Earth is flat, taking a journey with his wife, and eventually reaching a new land. The cartooning has evolved again, but while certainly not the standard daily strip, the 24 strips prepared in various stages lack charm or many laughs. Natalie is more traditional and accessible, Feiffer compromising, yet still including enough whimsy and individuality. These are funny, and there can’t have been many newspaper strips touted around in 1954 including a sample of young child boasting they’re the filthiest-minded kid in the neighbourhood. Sadly, poor reproduction loses Natalie’s response. However, Feiffer felt these too tame and conventional, so discarded the idea early.

This is a far stronger collection than the first volume’s concentration on Feiffer’s learning process when producing Clifford. He’s become an innovator, and continues to innovate in The Collected Works Volume Three, which reprints Sick, Sick, Sick in its entirety.