Review by Ian Keogh

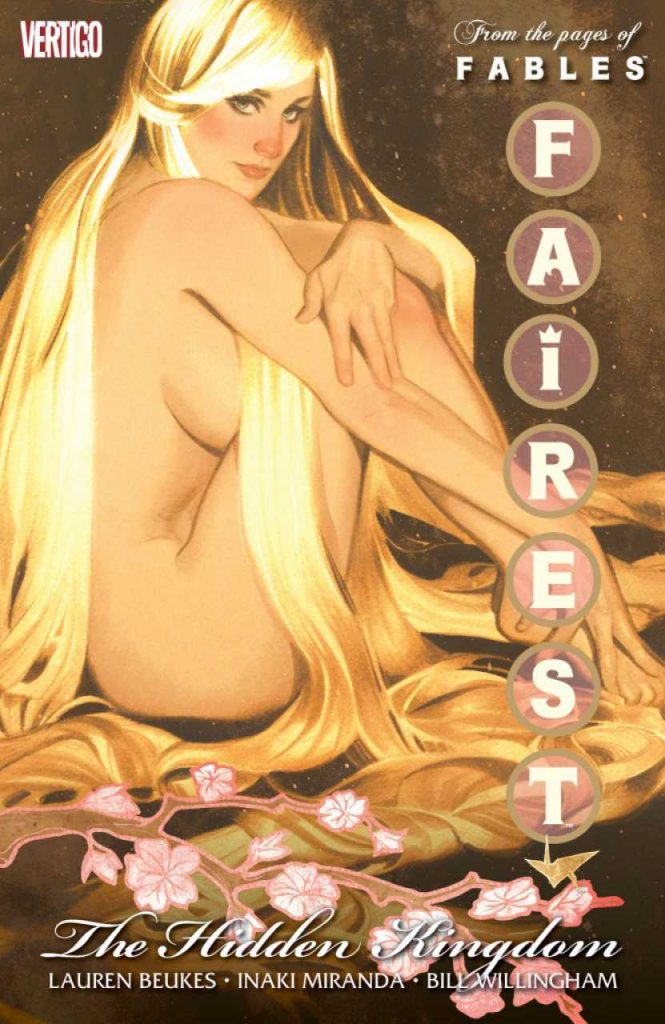

Rapunzel’s life is one of frustration. A Fables rule is that their presence in New York is to remain secret, so someone whose hair grows at a rate of four inches an hour can only have the briefest of contact with humans. It’s a restriction Rapuzel has reluctantly accepted, but when there’s a chance to discover what happened to her missing children, the rules of Fabletown are somehow less important.

Rapunzel is a character little used in Fables beyond the odd gimmick participation, so Lauren Beukes and Inaki Miranda have a fair bit of leeway in completing her back story, providing one surprising revelation in the first episode. Beukes establishes that at her lowest ebb centuries previously Rapunzel spent some time in the Hidden Kingdom, Japan’s equivalent of the Fables community, building friendships and relationships, but their nature offended the more conservative residents, some of whom have ulterior motives for wanting her gone.

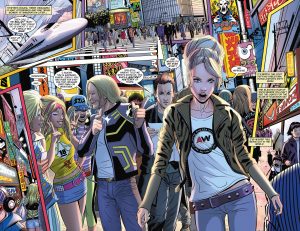

Miranda’s art is extraordinarily ornate, drawing on the mainstays of Japanese artistic culture, but with the colours supplied by Eva De La Cruz adding a contemporary brightness. He delivers page after page of extraordinary images, infusing the wonder of Studio Ghibli animation with modern day Tokyo, and designs dozens of brilliant looking characters. This is a graphic novel worth buying just to look at, but thankfully the story’s worth reading as well.

As Rapunzel’s trip through Japan continues, Beukes filters in snippets of her previous visit, and how that eventually turned very sour. The pacing is good, with what’s revealed about the past often affecting the immediate present, and the realisation gradually dawns that The Hidden Kingdom is a horror story with fantasy elements instead of the other way round. A weak spot is the inclusion of Jack of Fables. He’s needed for the conclusion, but the way of getting him to Japan is contrived, and he spends much of the book with no great purpose. Perhaps Beukes just liked his conniving character. It’s also rather disappointing that the element that prompted the story in the first place isn’t resolved. It’s left wishy washy, and while there’s enough reward that no-one should feel cheated, it’s certainly untidy.

A single chapter by Fables creator Bill Willingham closes the book, but by his standards it’s a shallow piece, and reads suspiciously as if the entire story is contrived around a single bad taste joke. It actually drags the overall quality down, but is nicely drawn by Barry Kitson, who’s unfortunate to be collected in the same book as Miranda.

Fairest graphic novels are standalone stories, but anyone wanting to follow the original publication order should pick up The Return of the Maharaja next.