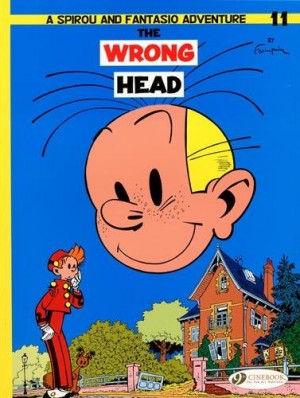

Review by Frank Plowright

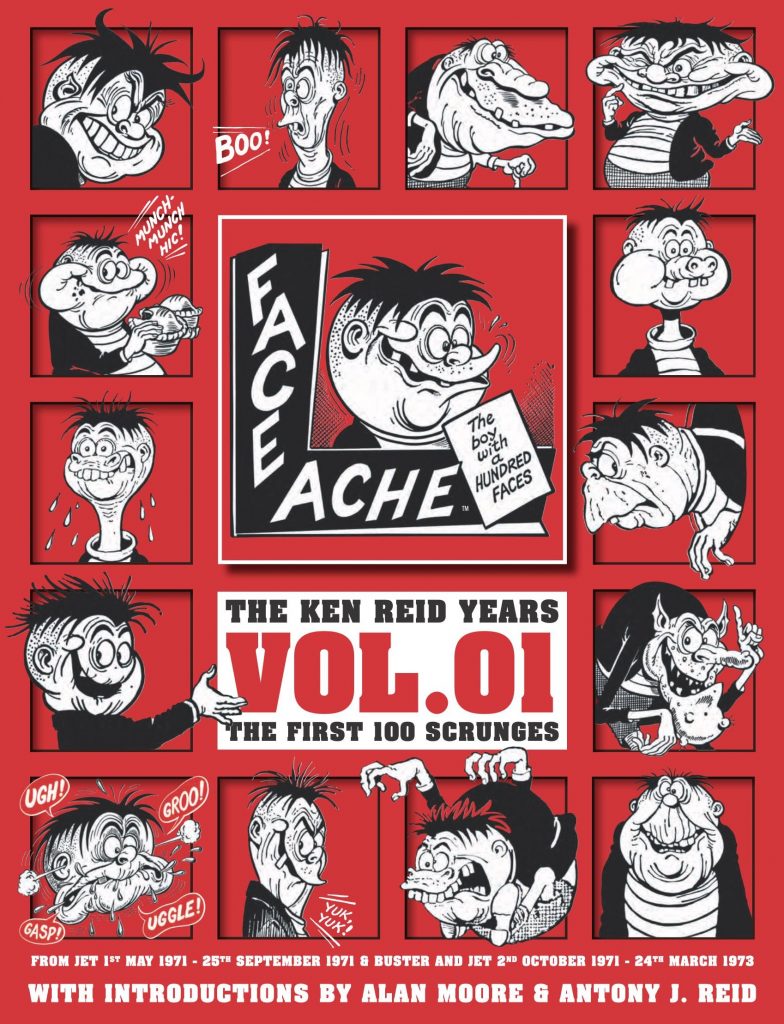

Ken Reid is a criminally unsung genius, a term not lightly applied. He thrilled the readers of British children’s comics from the 1950s to the 1980s with his stunning creations. Although Faceache ranks below a few other Reid strips in the eyes of connoisseurs, it’s his longest running, starting in 1971, and perhaps the most representative, singularly designed to showcase his talent for producing grotesque looking people strained to the limit to maximise their facial contortions.

Introduced in the opening strip as Ricky Rubberneck, then never referred to again by that name, Faceache was born with malleable features, able to contort and stretch his face into consistently scary forms. As Alan Moore notes in his introduction, these are relatively tame to begin with, but as the feature continues Reid grows more in touch with his inner demon and the faces pulled become ever more strange and bizarre. Considering the starting point, this is some feat. It’s also worth noting that under Reid’s watch very few characters appearing in the strip look normal. Over the book he creates an entire menagerie of oddities, many of them enraged at or driven to desperation by Faceache’s antics. Their faces are twisting, sweating, chinless, and they have odd spectacles, buck teeth, the thousand yard stare… Faceache is also notable for operating in an almost exclusively male world. In a strip about a family holiday his mother is featured for a panel, and in another for three, feeding him carrots. There’s a schoolgirl scared of spiders seen in a few panels, but the only other woman to feature in the book is a gruesome granny, designed by Reid to be every bit Faceache’s ugly equal.

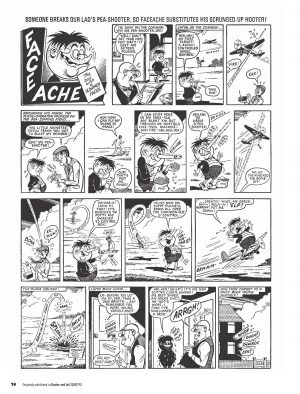

Humour features in British children’s comics were traditionally only allocated the single page, but Reid packed his densely, generally fifteen or sixteen panels over four tiers. One extends that to an incredible 23. It was required because Reid’s scripts were miniature masterpieces of consistent invention as Faceache applied his talents to one scheme or another and Reid didn’t short change on gags. Faceache’s a proactive and mischievous character, instigating trouble rather than reacting to it, and Reid’s imagination is fantastic. Memorable strips have him adapting his nose to the form of a double-barrelled pea-shooter, appearing as a monster crawling from a sinkhole, and twisted around the mechanism of the town clock. Themes recur, not least the British period obsession for spanking children, but over the content here at least Reid’s remarkable for not recycling material.

Toward the end of the what’s included Faceache’s transformative abilities extend to his entire body, but rather than being a UK version of Plastic Man, he changes into a menagerie of bizarre creatures, Reid’s imaginative renderings both hilarious and disturbing. It’s eventually indicated by a new, more sinister, logo panel, but before then Faceache’s already been changing into monstrous ducks and other creatures.

Not every strip is Reid’s work. Other artists approximate Faceache for two periods of 1972’s output, but while they come close to his art, it’s far from exact. They use fewer panels, provide less detail, and much black ink remains in the pot. They’re decent artists, but are following Reid’s lead and don’t have his devotion to density. Two scripts are credited to Ian Mennell, a versatile writer who contributed to girls and humour comics.

This is volume one as it only extends two years into the sixteen Reid drew the feature, sadly dying as he worked on his final episode, and is extremely welcome. It’s hoped it does prove to be the first of a comprehensive collection of his remarkable output.