Review by Ian Keogh

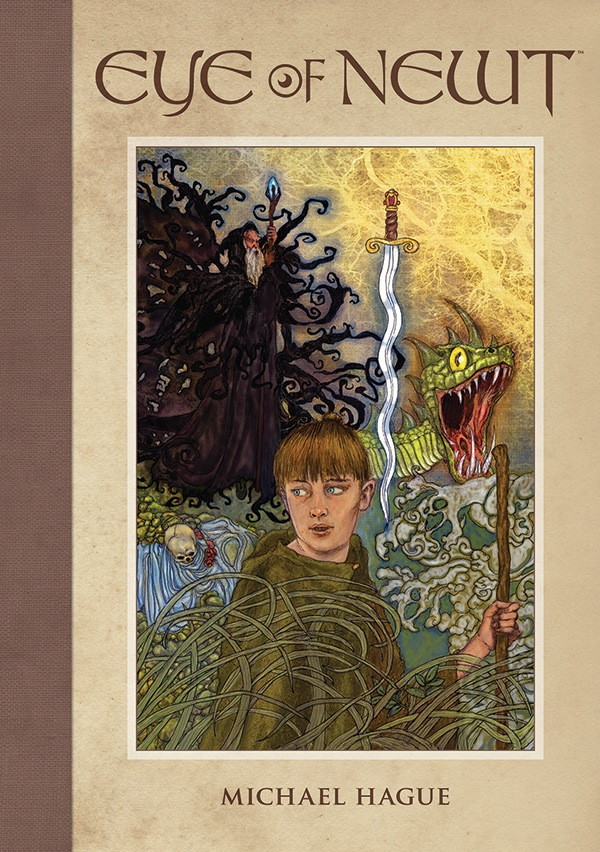

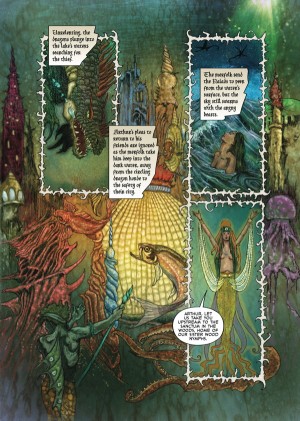

The sheer amount of hours Michael Hague must have invested in constructing each of the ornate fantasy pages compared with the average page of comics beggars belief. There’s a richness of texture and prioritising of decorative quality that’s absent from the work of an artist having to complete a page a day come hell or high water.

Hague’s background is book illustration, and his paintings grace editions of many standards of literature, his style echoing turn of the 20th century children’s book illustrators. Arthur Rackham and W. Heath Robinson are visible influences, and the look of his dragons and wizards is in the classical style.

Hague’s story follows the well-trodden coming of age path. Newt is a form of sorcerer’s apprentice and to complete his training he must venture into the netherworld and retrieve an object of magical power. The stronger the object he retrieves, the more powerful he will be. How he performs will also reflect on the wizard who trained him, and as we see early, Newt is young, inexperienced and easily deceived.

Intended for youngsters, Eye of Newt is a confusing tale, and for all the undoubted quality of the art, Hague would have been better advised working with a writer. His career has been in producing the single representative image, and there seems to be little understanding that transition illustrations are required for comics. There are frequent occasions when even a simple caption stating “Later” would have worked wonders to avoid confusion, and that’s not the only troublesome aspect. Hague’s art compensates for some leaden and clichéd prose, but there’s a great irony in an early sequence of Newt’s teacher emphasising that during his task Newt must remain focussed. Hague neglects his own advice. He introduces one convenient element after another, as Newt follows random encounter with random encounter, most serving little purpose other than enabling Hague to paint another strange creature. He is working in the simplicity of the fairy tale tradition, and this precludes all but the most basic character development, but the feeling is that Hague’s just not capable of anything other than exposition and was plotting as he went along. All the trappings of classic fairy tale fantasy are here, but not in any cohesive fashion.