Review by Ian Keogh

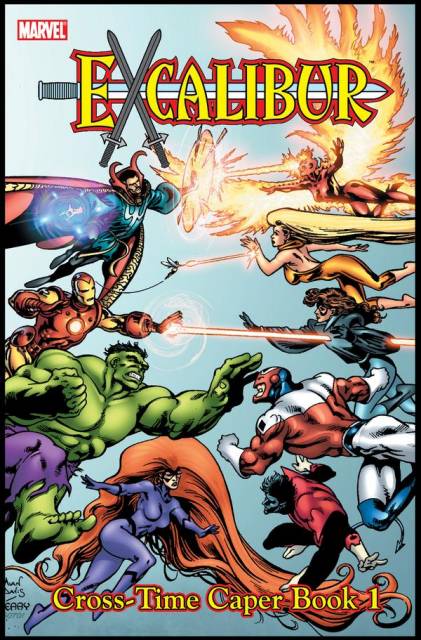

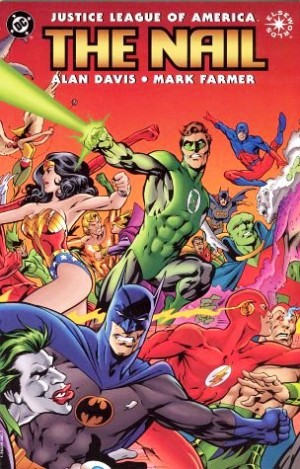

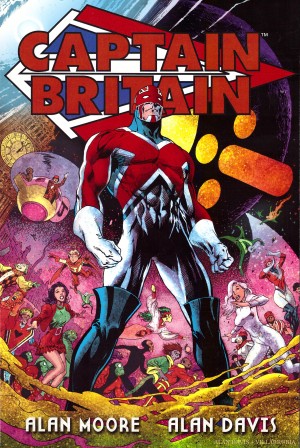

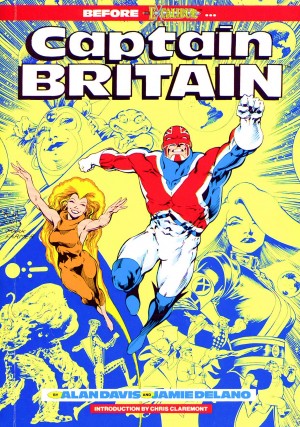

Chronologically this is the third Excalibur graphic novel, and the one where it started to come off the rails. The series to this point, now most readily available as The Sword is Drawn, had continued the surreal comedic tone established in Captain Britain’s previous series along with solidly plotted stories and, was for the most part, impeccably illustrated by Alan Davis.

Davis actually illustrates more of this book than the previous volume, and even contributes to a couple of the plots, but mining many other good points from the rambling whimsy is a difficult task. Excalibur were aboard a train designed to cross dimensions when the transportation device was activated. Over the course of this collection, and, lord help us, the next, they’re transported to a series of alternate worlds attempting to find their way home. This wouldn’t be any kind of problem if the individual stories were inventive enough to dislodge the idea that they’re a method of marking time, and if the short sequences set back on Excalibur’s own Earth weren’t more interesting.

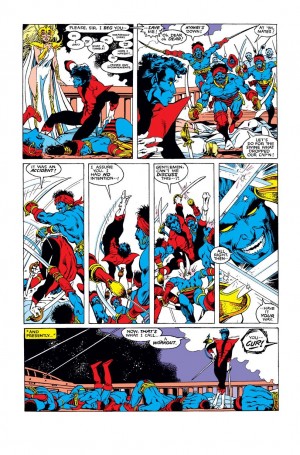

Some elements sunk in the morass do work. It’s overplayed, but Chris Claremont sets a nice dramatic plot of Kitty Pryde moon-eyed over scientist Alastaire Stuart when he fancies her friend Rachel Summers, Phoenix. The fate of Hank Pym is interesting, the Technet chapter has more than its share of laughs, and the episode with Nightcrawler as Warlord of Mars is the best in the book. Claremont at least appears to have his heart in this one, as Nightcrawler’s swashbuckling character works well in what for him is a natural environment despite being a fantasy land. Davis co-plots and the pair of them thrown in every fantasy joke they’ve ever wanted to work with.

From there it’s all downhill to a truly awful final chapter. Part of the problem is that while Claremont jamming the whimsy button down hard is drawn by Davis at least there’s the decorative art to distract from the lack of subtlety and ever increasing superfluous dialogue. With Davis replaced by far less talented artists any charm vanishes.

It’s presumably only for the sake of completeness that the final chapter is included. By Michael Higgins and Ron Lim, it’s a virtually plot-free zone with no connection to main the story. While accepting that fill-in issues are occasionally inevitable for monthly serialised comics, why include them in collected editions?