Review by Karl Verhoven

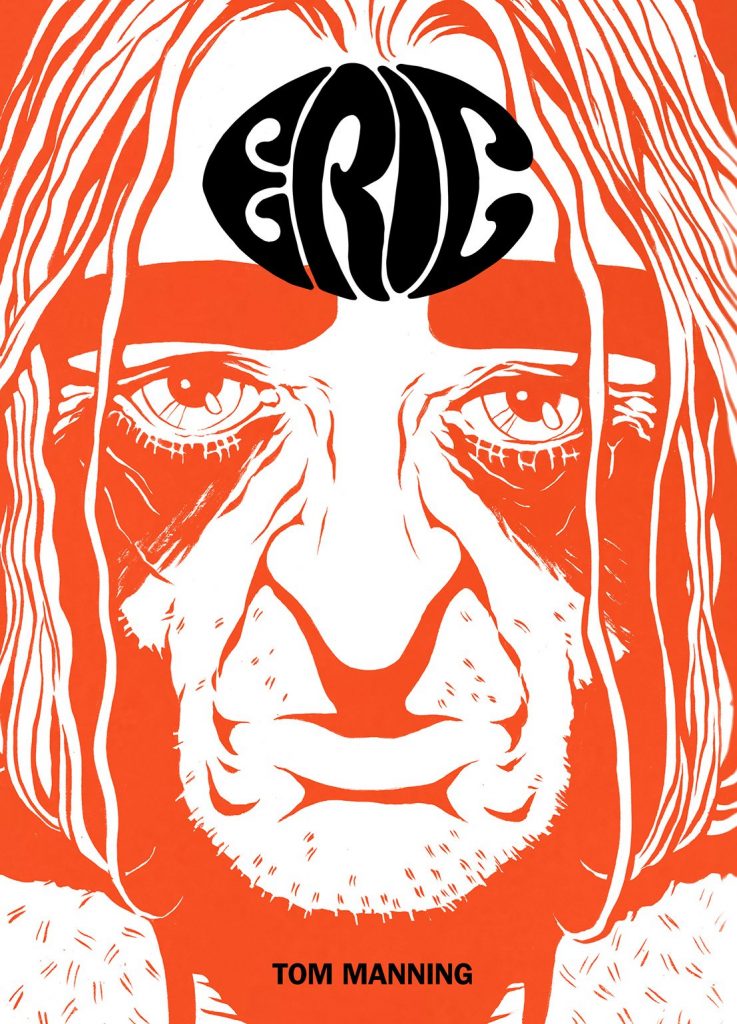

Eric was once a bonafide counter-culture hero, his recordings resonating throughout the 1960s, and he’s never discarded the values they espouse. Tom Manning provides a smart snapshot of his personality when he’s introduced phoning his manager at three in the morning venting about a 22 minute track he considers his masterpiece being absent from a just issued compilation. It’s followed by a phenomenally fried promo appearance on a trivial morning chat show.

Ego and entitlement accompanying vulnerability is hardly unique in entertainment circles, and to that Manning adds abuse of psychoactive substances stretching back decades, constructing an Eric whose connection to reality has become increasingly tenuous. Just how tenuous is revealed via an astonishing visit to the mother of his child after decades, following a sequence of Manning running through Eric’s recording history. This phases in influences from the Jimmy Boyd to the Residents via Warren Zevon’s chapter title, and a characteristic of Eric is that once references to songs, films and novels are first noticed they’ll recur again and again, repurposing reality becoming a theme.

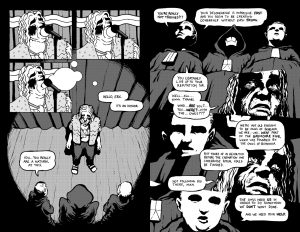

“I’m the Mayor of the Sunset Land, with a Pacific Pass to the sea and sand”, Eric sings on his big hit Beach Bum #1, “so let the campfire light cast a spooky sight, ‘cus the Beach Bum Number One’s here tonight”. Manning obviously enjoyed supplying 1960s style lyrics, performances and attitudes, and there’s some artistic nuance in gradually moving Eric further from reality. He frequently appears as a cartoon when in real surroundings, and in other places is heavily rendered, his dissolute life etched on his face, although at times more separation between panels would provide greater clarity,

Fun though it is, the career recap is by way of establishing Eric and his paranoid world. Is he disintegrating or transcending? The actual opening scene is some form of mystical ceremony, and by halfway the consequences of that have fully bloomed, as Eric is thrown into a world extrapolating conspiracy theories. When not addled Eric has a massive sense of his own self-importance, and it turns out to be one matter where he’s not misguided. Realities beyond ours exist, and there are methods of connecting.

So what is Eric? It’s a genre-straddling achievement taking some wild, but always fascinating swerves, requiring Manning to have considerable artistic adaptability. He repurposes the familiar with sinister intent, such as a sequence requiring considerable planning just to travel on a train, with horror and western then the predominant genres. There’s a richness to Manning’s presentation, whereby there’s always a feeling that something isn’t quite slotting together, but precisely what that is remains elusive. It may parallel Eric’s frequent state. Seeming trivialities from Eric’s first half resonating in the second are audaciously expanded, and scene-switching at the most inopportune moments is an exquisite torture. Manning convincingly sells Hippy Philosophy 101, and adroitly subverts expectation via mystic realism.

An ambiguous ending may not be a crowd pleaser, but is hardly without precedent considering the journey taken, and it’s consistent with the reader left to fend for themselves regarding the meaning of some aspects. Does the water herald rebirth? Is the discussion of form and reality relevant to the ending? It’s simultaneously frustrating and intriguing, but ultimately a weakness. Despite Manning emphasising individual experience, most of us want the conformity of a clever resolution to a clever story, and feel cheated by an ending not supplying that. Whatever your feeling about enigmatic endings, it shouldn’t blind you to wonderful journeys, and Eric provides one.