Review by Frank Plowright

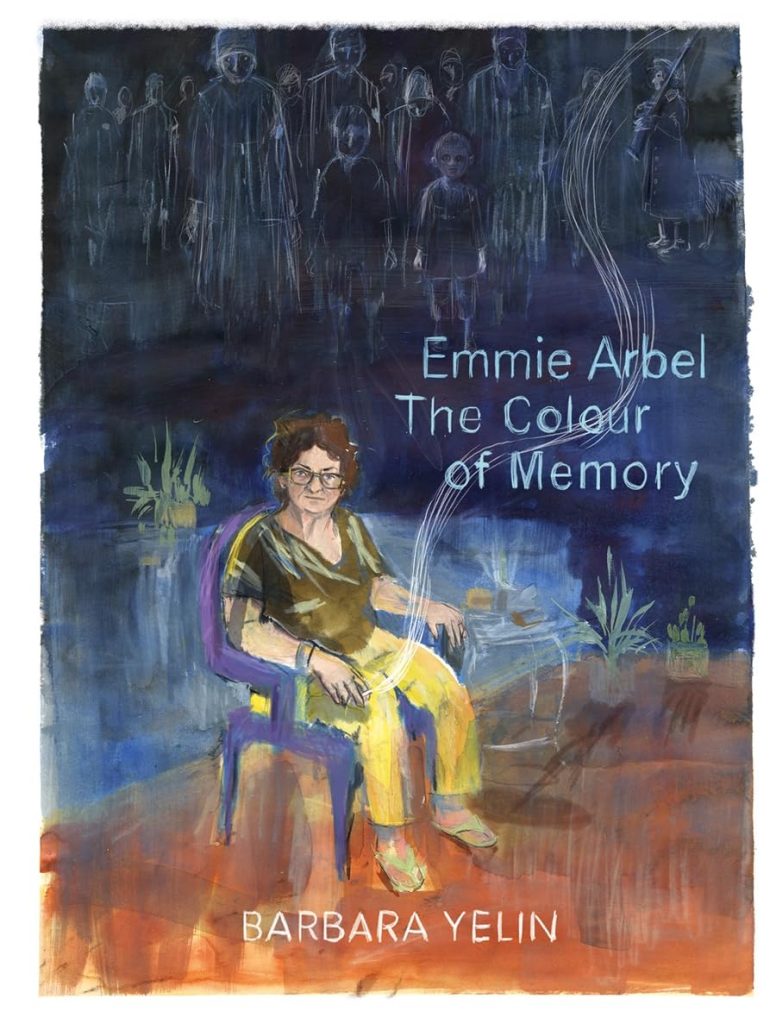

Barbara Yelin’s previous graphic novel Irmina was a biography of her grandmother, with life in Nazi Germany a focus and revealing some callous attitudes the author would perhaps not have wanted to hear. It’s perhaps natural, then, that Emmie Arbel: The Colour of Memory revisits the same period through the eyes of someone whose experiences were altogether different. Born in the Netherlands and Jewish, Emmie Arbel was tragically in the wrong place at the wrong time in the 1940s.

In her afterword the German Yelin concedes in hindsight that her conversations with Emmie answered questions about herself and, although she doesn’t use the phrase, generational guilt was a factor. The feelings involved add an extra layer of interest elevating Yelin’s work beyond the fair number of other graphic novels concerning experiences of the Holocaust published since 2015, most of which can be recommended.

Emmie’s story isn’t told chronologically, but in fragments jumping back and forth through the years, which is possibly a process devised to reflect the gradual retrieval of fractured memories of matters deeply repressed for decades. The art is similarly elusive, blurred and vague, with faces only rarely distinct, but Yelin never sensationalises. The approach is evocative and leads to startling revelations sometimes being almost offhand remarks. At a visit to former concentration camp site Yelin asks whether people swim in the nearby lake and is told they don’t because it’s filled with ashes. No further comment is necessary.

The style also reflects the way Emmie’s story was disclosed over many conversations in many places. They’ve been editorially sorted, but dates are supplied for the original talks. The revelations may be piecemeal, but they’re fascinating and prompt questions that remain unanswered. Emmie’s childhood memory of being reunited with her older brother after years apart in concentration camps was to wonder why he wasn’t wearing a hat in cold weather.

If this was just the story of Emmie World War II survival it would be remarkably told, but more horrors await, and the combination creates an uncompromising, rebellious and difficult person unable to trust and with an over-riding desire to remain free. Her daughters were adults before she could talk properly with them, and then only after a decade of therapy. At times the elderly Emmie can seem distant and closed off, her comments shocking, but then there are moments of supreme sacrifice, such as saying she’d willingly repeat her Holocaust years if another death could be avoided.

In today’s climate with countries looking increasingly inward it’s important that the lives of persecuted people like Emmie’s are told. Yavin does this with clarity, compassion and understanding.