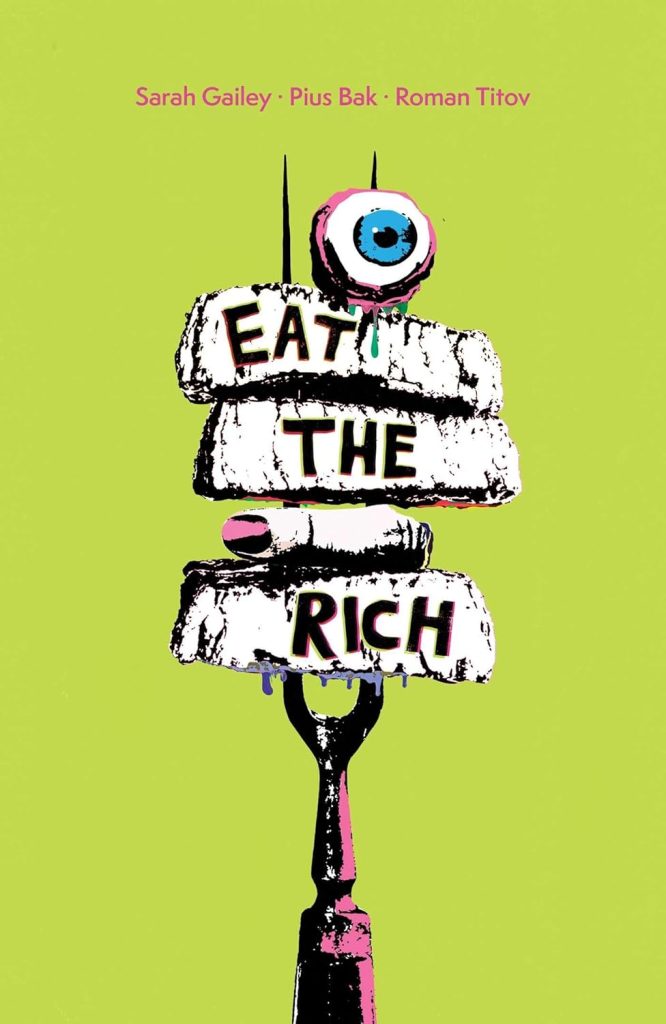

Review by Ian Keogh

Astor’s family is immensely wealthy, and as Eat the Rich begins he’s on the way to visit with girlfriend Joey, who’ll be meeting them for the first time. For different reasons both are nervous, and it’s Joey’s narrative guiding readers through her discomfort as she tries to fit into a world well above her expectations. Sarah Gailey also toys with readers by ramping up the tension as she shows Joey witnessing the family’s infant son pulling a jawbone from the beachfront sand. And if circumstances weren’t uncomfortable enough, it turns out there’s a tradition of combining parties with roasts, of the alleged comedy kind. After that it turns really nasty.

Part of what sells the horror so well is Gailey’s twisted imagination, but Pius Bak’s art is from the school of Sean Phillips, a studied realism that enables atrocities to seem part of natural life, which in the circles Astor’s family moves in, they are. Because of where things head, Bak’s character designs need to be spot on because we’re seeing people in emotional extremes, so they have to service those moods, and his people all have the necessary visual depth despite being relatively simply drawn. When it comes to the surroundings, Bak is nowhere near as diligent as Phillips. We’re supposed to be seeing people living opulent lifestyles afforded by wealth beyond imagining, but beyond a couple of panels in the early stages everything could take place in your neighbourhood.

After Joey’s initial shock and repugnance, Eat the Rich’s theme is the cost of compliance and the chilling acceptance of a different form of reality. Most of the shock is front-ended, and once the parameters have been established and the monsters revealed, the remainder is reminiscent of the tension generated by a good Alfred Hitchcock film where readers will be rooting for an impossible escape.

Unfortunately, that’s not sustained until the end. One character in particular seems contrived to tick several boxes, and their prominence increases throughout, while one particular logical question will occur and remains unaddressed until Gailey’s afterword. Having set up an appalling problem, Gailey takes the easy option for the final scenes, which solves it, but in a dashed off manner, and by then Bak’s art is less imaginative, increasingly reliant on faces in close-up that can be drawn quickly. There’s a lot to admire in the set-up and suspense, but Eat the Rich doesn’t entirely deliver.