Review by Frank Plowright

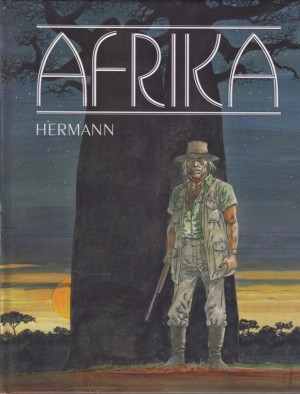

Frank Bellamy is a titan among British comic artists, but one whose best work appeared before the onset of organised fandom, and who died tragically early in 1976. His most sustained work was producing the Garth newspaper strip from 1971 until his death at 59, the Book Palace have issued collections of his earliest strips King Arthur and Robin Hood, and many fondly recall his Thunderbirds. Talk to the real enthusiasts, however, and they’ll tell you his finest work was Fraser of Africa.

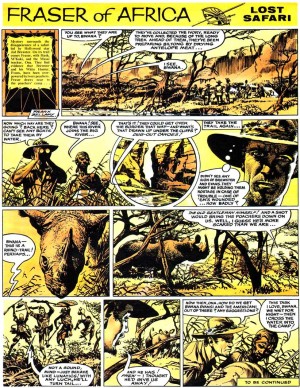

Prior to starting the strip in 1960 Bellamy had completed a year working on The Eagle’s flagship character Dan Dare, and while the space-based science fiction would later inform Garth, this wasn’t a particularly happy experience. Fraser, therefore came as a liberation, and he responded to the adventures of a big game hunter in Africa by meticulously researching his locales, and creating what’s still a unique look for a strip. Before the skilled stippled shading and dynamic illustrations become apparent, any reader will be struck by the evocative limited palette Bellamy constructed to reflect the searing heat of the African continent. He devised a method of colouring almost the entire strip in shades of yellow, orange and brown, which significantly tested the printing limits of the era.

An aspect of the strip surprises, although perhaps it shouldn’t given the meticulous standards of The Eagle in general; Martin Fraser may be a tracker and hunter, but in George Beardsmore’s scripts he doesn’t kill indiscriminately, and he maintains a respect for both the native population and the wildlife he encounters. Fraser is a knowledgeable man attuned to his surroundings, a conservation agenda in stark contrast to similar material in contemporary boys’ adventure comics of an era that rarely reflected Britain’s then post-colonial status.

Three episodes comprise the entire run of this remarkably drawn strip. ‘The Lost Safari’ has Fraser tracking a missing expedition led by a Hollywood film star, ‘The Ivory Poachers’ is pretty well self-explanatory, as is ‘The Slavers’, although that story isn’t as straightforward. It’s briefer, and despite an early twist, while the art never slips, the story is ultra-compressed. Bellamy would soon begin work on a more renowned strip, Heros the Spartan.

The enticing oversize package is rounded out by an extensive biographical essay by Norman Wright explaining many background details.