Review by Ian Keogh

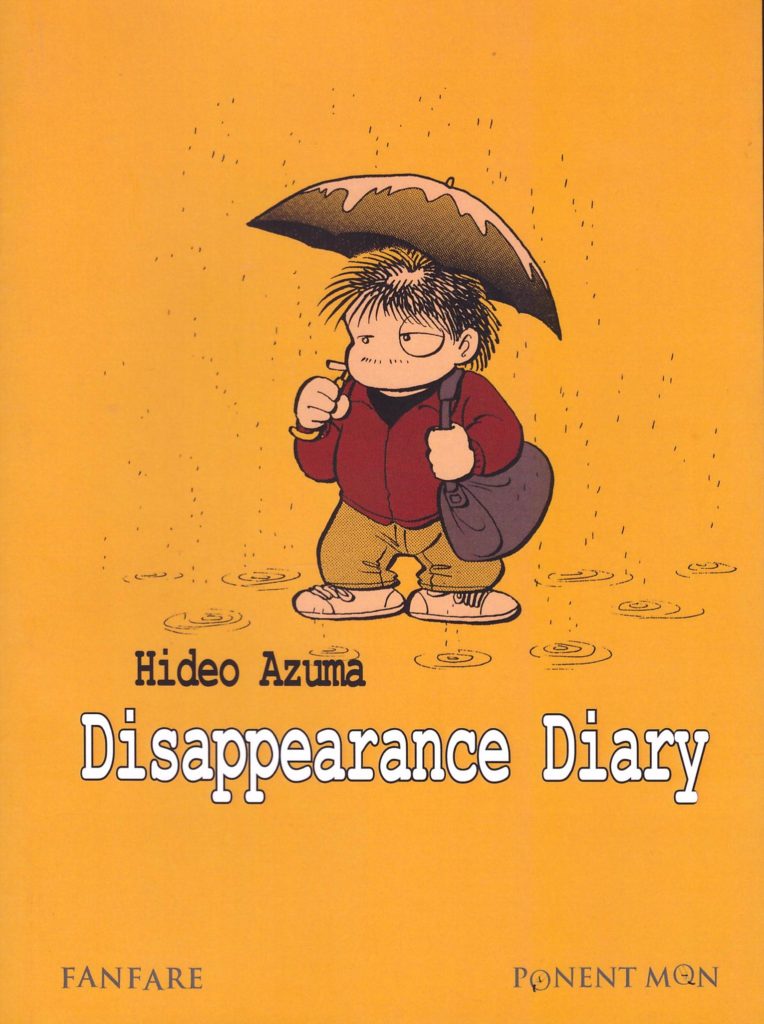

Depressed and alcoholic, Hideo Azuma details how one day in 1989 he told his publisher he was going out for cigarettes and just left all his responsibilities behind. While ostensibly away from home researching a new project he took things a step further and didn’t bother returning to his wife, instead spending a period sleeping rough. In 1992 he essentially repeated the procedure. Yet as he states at the beginning, his outlook on life is essentially positive, and by drawing in beautifully delicate bigfoot cartoon fashion he removes the sting from some jaw-dropping experiences.

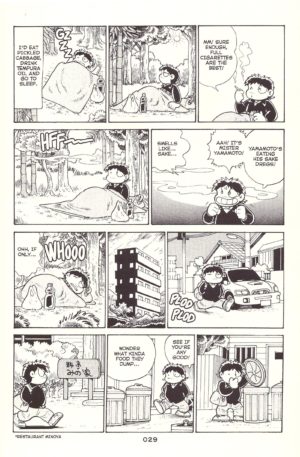

By page eight Azuma is sleeping rough, and it astonishes how easily he drops into the life of a homeless scavenger, rifling through bin bags and dustbins to assess how inedible anything he finds might be. Weirdly, as Azuma recounts what he learned about staying fed and able to sleep, his recollections almost become a primer for urban survival without a home. Some people discard the chocolate bars they buy only for the accompanying sticker, and soy sauce makes lumps of pork fat edible. Azuma doesn’t trivialise his problems, but the representation may be too glib for some, and as surprising as it might be from a person happy to show himself prying the eyes from a discarded fish head to eat, he’s also holding back a little. Everything is matter or fact, but the opening section is heavy on behaviour, without thoughts on the causes. Nor is there any reflection on the wife he left behind. Aspects of depression, alcoholism and mental illness can’t be rationalised, but that Azuma doesn’t attempt any hint of motivation leaves Disappearance Diary a little lacking until the final segment.

After a period of recuperation and rehabilitation, Azuma resumed his career, but then left home again, first living aimlessly in a park, then adopting a more structured approach to his absence. He moved to a different city and became a gas pipe fitter. Eccentric and fractured they may be, but recollections of his workmates and his time working with them aren’t as interesting, despite featuring the same refined cartooning Azuma applies to the remainder of his experiences. He picks up again when discussing his previous manga drawing career from the 1970s. The sheer tyranny of the editors and the insane work schedules demanded are eye-opening, and give an understanding as to why so much manga is restricted to figures. The work demands prove a major factor in Azuma’s alcoholism.

Azuma’s experiences leading to his admission of alcoholism and the subsequent treatment occupy about fifty pages, and they’re the most compelling sequence. They’re completely honest in showing the degradation and sheer determination needed for the first stage of recovery. It’s detailed in a way few will know without requiring treatment themselves. Some cautionary tales are heartbreaking and others repulsive, the reason for the cartooning taking the edge off now clearer. The graphic novel itself is proof that Azuma came to terms with himself and his condition, which isn’t clear from an abrupt ending promising more that isn’t available in English. Some further insight is provided by two accompanying interviews, one on the endpapers.

Disappearance Diary is a confessional memoir to put all but the most compulsive admissions of others to shame, yet the brutal honesty may also serve as a wake-up call, educating as it entertains. It won the Grand Prize at the 2005 Japan Media Arts Festival.