Review by Frank Plowright

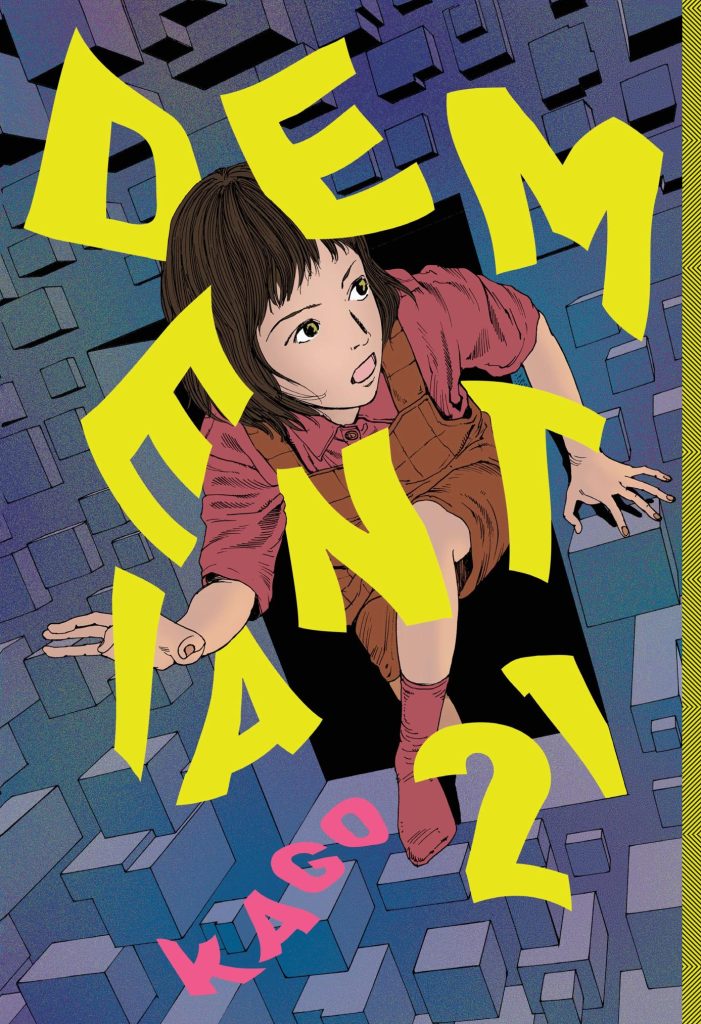

Yukie Sakai is a carer employed by the Green Net organisation. Despite being relatively new to the company her competence and friendliness ensures she constantly tops the rankings for customer satisfaction. It frustrates the longer serving Ayase who convinces her boyfriend to tamper with the system. He adds a wave of post-visit complaints to Yukie’s file, relegating her to the worst performing aide, which means she’s sent to the house where carers keep disappearing. It’s here that Dementia 21 turns from a real world form of horror to a traditional form, although that’s only the beginning.

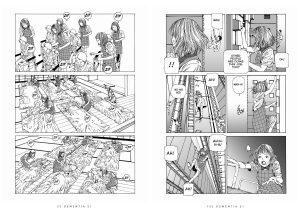

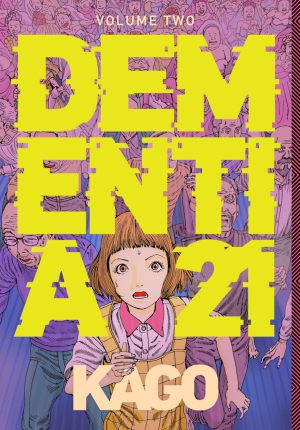

A further sixteen stories follow with creator Kago creating increasingly absurd tasks for Yukie to overcome while she’s desperate to raise her customer scores. The sample spread features art from a story where she’s given the already very difficult task of caring for three elderly, bedridden ladies, yet their family keep adding more, and the second page concerns a fully automated nursing home that’s gone rogue. That resembles the wacky ideas John Wagner and Alan Grant fed into 1980s Judge Dredd stories, and indeed develops into something resembling a Block War. Like Judge Dredd, Dementia 21 is a constant repository for bizarre ideas, some hilarious, others stunning. However, given a longer page count Kago has greater room to explore things like rogue dentures, roads separated for use according to the driver’s age or profession, and a war scenario lottery for the few available places in a desirable nursing home.

The result is a conceptually dense parade of atrocities with Yukie the put upon everyperson in the middle of something they can barely comprehend. The attractive, but simple drawing suppresses exaggeration, so raises the humour level, and a lot of work is put into complex panel compositions and occasional toying with the form. That’s most apparent via the exploitative twist on the ‘it was all a dream’ scenario when Yukie works for an ageing manga creator and is drawn into his strange world. It’s rare for also providing a definitive funny ending rather than a wandering away from chaos. Occasionally, though, Kago disappoints such as the uninspired 1950s SF homage near the end.

Almost as funny as the stories is editor Gary Groth’s attempt to have Kago answer a few questions about his background, life and work, and running up against a brick wall. Kago would prefer people divine his views from his stories. The only constant to what’s presented here is the idea of the elderly being considered a burden for families and society, occasionally supplemented by family members presented as greedy, resentful or both. Beyond the satire, is he working out his own conflict?

No matter the appalling circumstances in which Yukie ends a story there’s a reset button. She’s healthy and determined to raise those scores again by the start of the next, and Kago keeps making surreal additions, many of which recur. Paranoia abounds and is creatively exploited, but such is the density of ideas this is better sampled a few stories at a time rather than a deep immersion in Kago’s world. As clever as Yukie’s torments are, after a while you’ll overdose on them. Still, moderate use will leave you in good shape for Volume Two.