Review by Frank Plowright

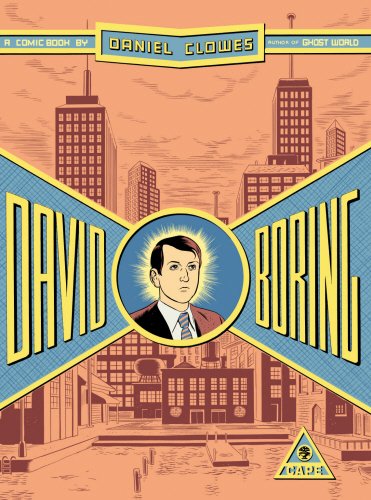

Creator Daniel Clowes describes David Boring as a story in three acts, all three cemented with either comments about making movies or movie references. To underline the point, a fictional cast listing is provided. Boring is the protagonist of his own internal narrative, confessional, self-aware, barely out of his teens and with obsessive tendencies rooted in his defined ideal of the perfect feminine form. It results in sex lacking any emotional investment and a series of neurotic obsessions with women.

It’s a clever first person narrative far more influenced by film than comics, with an all-pervasive, carefully cultivated air of constant tension and foreboding. This is provided by symbolism, the vague threat of war and/or terrorist action, ambiguity and characters deliberately reacting against type, as if aware of their narrative strings.

The quest is a recurring theme. Despite occurring over a lengthy period, it’s only when his narrative concludes that Boring lacks a search, whether it be for a woman, his father, a comic, or perfection. That the story ends in a form of success that enables a seemingly perpetual replay appears yet another knowing nod to movies, tying matters up in improbable fashion.

The centrepiece traps a number of characters on a remote island where pre-millennial tension erupts to pull them and their relationships to pieces in what’s almost a literal dissection. Their disparate personalities are constructed to deliver soap-opera style emotional conflict, yet David Boring floats through the debris almost untouched. He has a provocative name, and while he doesn’t live up to it, his distanced personality and the structured behaviour of those surrounding him fail to create an emotional bond. He drifts with an expectation of shaping life to his own ends. Clowes also chooses to downplay anything that could be considered a traditional action scene, even within the faked comic that Boring scans for insight into his father’s character.

There also appears to be a form of self-criticism at work if comics are substituted for comments about film making. “Every story has been told, so if you have to tell one, tell it well” is one comment amid references to the stalled creative process. Or perhaps that’s just reading too far. The elusive nature of substance here invites such speculation.

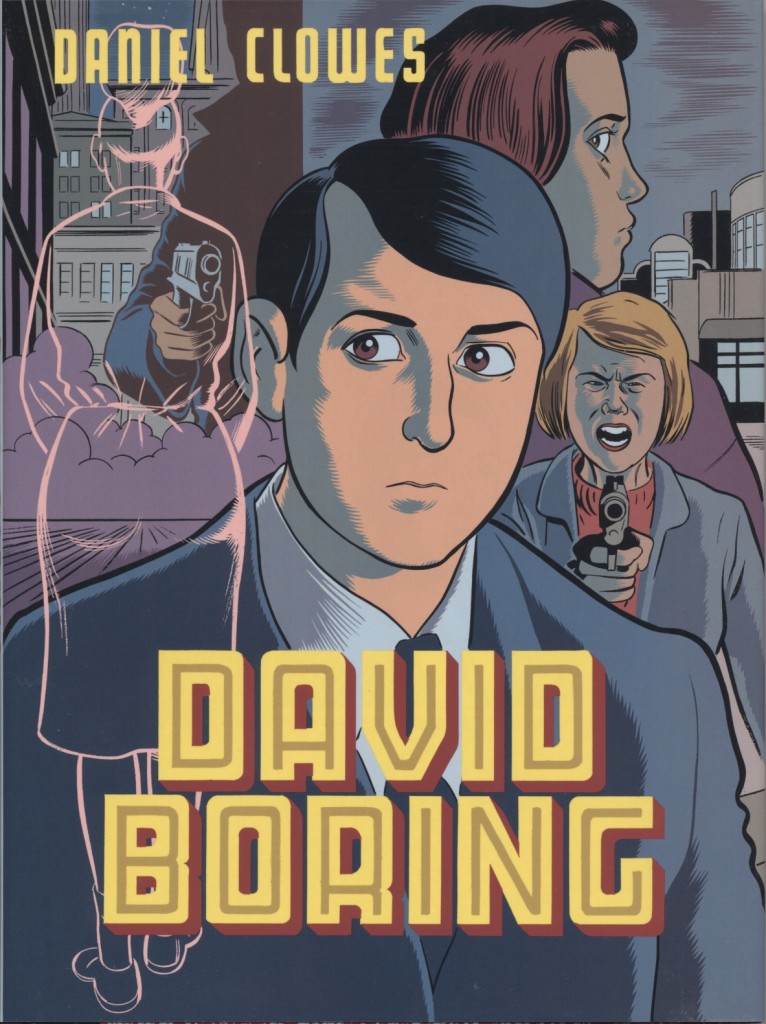

Clowes’ art was his best to that point in career. His characters had lost their perpetually haunted look, although there’s always a posed stiffness, despite an odd serenity to some. Boring himself is predominantly expressionless, even at moments of heightened emotion, only losing himself to anger on one occasion, although this could also be role-playing.

David Boring is a well constructed and sometimes surprising story that fails to engage completely. Yes, it’s very good, but it wasn’t Clowes’ finest work even in 2005 when Time magazine listed it among the top ten graphic novels of all time. Had they seen Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron? It explores much the same emotional territory in more visceral and disturbing fashion. David Boring could, in fact, be a different directorial interpretation. Alain Resnais as opposed to David Lynch.